Transitional justice is mandatory for democratic states, implies a full acknowledgement and rectification of past abuses, and requires the cooperation of civil society.

by Massimo Introvigne*

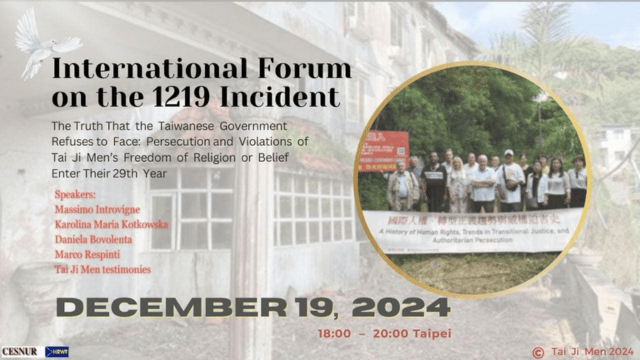

*A paper presented at the webinar “International Forum on the 1219 Incident, The Truth That the Taiwanese Government Refuses to Face: Persecution and Violations of Tai Ji Men’s Freedom of Religion or Belief Enter Their 29th Year,” Taipei, December 19, 2024.

December 19 is the date Tai Ji Men has proposed for an International Day Against Judicial Persecution by State Power. The words “transitional justice” are not included in the title of the new International Day. However, the idea of transitional justice is clearly included in the proposal. In fact, only transitional justice can rectify the consequences of past judicial persecution by state power and make sure human rights violations will not happen again.

In this important day, I would like to emphasize three key points, which also reflect on the Tai Ji Men case in Taiwan.

First, transitional justice is mandatory for democratic states. It is not optional. It is not something states may decide to implement or not to implement according to their political needs. States that do not abide by the transitional justice principles are not democratic and rightly receive international blame. Scholars came to this conclusion based on a significant number of decisions and documents from the United Nations Human Rights Council, the European Court of Human Rights, and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights.

Taiwan is not a member state of these bodies. However, all are based on the principles of the Two United Nations Human Rights Covenants. Taiwan has incorporated the Two Covenants into its domestic law in 2009. Thus, it freely promised to be bound by them. According to the majority interpretation of international law scholars, this also meant that Taiwan implicitly promised to implement a fair and comprehensive international transitional justice. This is now mandatory, not optional, for Taiwan. And “fair and comprehensive” means that Taiwan cannot limit its transitional justice to violations committed before a certain date. All should be addressed, including those connected with the 1996 political crackdown against several spiritual groups, which also affected Tai Ji Men.

Second, the four principles of transitional justice are connected with each other. The term “transitional justice” was coined by scholars after the fall of the Soviet Union and several Latin American dictatorships in the late 1980s and early 1990s. However, principles of transitional justice, without calling them with its name, were established post-World War II with the Nuremberg and Tokyo trials of Nazi and Japanese leaders for human rights violations and crimes against humanity. Transitional justice aims to ensure peace, stability, and democracy when moving from a non-democratic regime by addressing past evils. Many international decisions mention the four principles listed by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in 1988 in the case “Velásquez Rodríguez v. Honduras.” They are preventing further human rights violations, investigating past crimes, punishing offenders, and compensating victims.

The Inter-American Court also explained that the order in which it listed the principles was not coincidental, and that the four are strictly connected. One cannot be implemented without all the others. The court listed as first the aim of preventing further violations of human rights. This means, first, that the most important aim of transitional justice is to guarantee democracy now and in the future. Crying about past abuses without addressing present wrongdoings is hypocritical. Second, however, it is impossible to avoid the continuation of abuses without clearly denouncing those of the past, punishing those responsible, and indemnifying the victims.

Taiwan is unfortunately not the only example where this has not happened but is a quite spectacular one. In the case of Tai Ji Men, there has not been a clear and public acknowledgement that injustice was perpetrated through the fabricated case. Those responsible have not been punished. On the contrary, the main perpetrator, Prosecutor Hou Kuan-Jen, has been promoted to higher office. And there has been no full indemnification of Tai Ji Men. On the contrary, its sacred land has been nationalized based on a tax bill several authorities admitted was false, unfair, and fabricated. Opportunities to rectify this situation have not been used, as it happened recently with the unjust decision of the Taichung High Administrative Court rendered on August 2, 2024. The Tai Ji Men case offers additional evidence of the principles set forth by international law about transitional justice. If injustices of the past are not rectified, there would be no justice in the present either.

The third key point is that transitional justice is not a task entrusted to governments and courts of law only. Their role is necessary, and they should be held accountable if they fail in their task. However, it is increasingly recognized that transitional justice is a joint effort where civil society also plays a decisive role. Dr. Hong Tao-Tze, the Shifu (Grand Master) of Tai Ji Men and his dizi (or disciples) have continued for twenty-eight years to affirm and protect their innocence and their human rights, and to call for transitional justice. Admirably, they did not ask for justice for themselves only. They identified a broader problem of transitional justice in Taiwan, became recognized experts and professionals on the issue, and proposed solutions that would benefit many other groups and Taiwanese society as a whole. More, they gathered an international community of scholars and human rights activists who both support Tai Ji Men and through webinars and events advance the global cause of human rights and transitional justice.

For this, proclaiming an International Day Against Judicial Persecution by State Power is a sign of rightful protest. But it is also a sign of hope.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.