After the use of ayahuasca was abandoned, the experiences continued through guided meditation techniques.

by Susan J. Palmer

Article 2 of 3. Read article 1.

Mikis Hasson, the founder of TierraMitica whom we met in the first article of this series, describes ayahuasca as “a mixture of two different plants, the Chukruna and the Ayahuasca; one holds a chemical called DMT and the other an enzyme necessary for absorption by the body.”

Hasson noted in our interview: “Together, they make a psychotropic potion that can heal trauma, and open the heart connection with the divine, and facilitate a face-to-face discussion with one’s subconscious. Since it is a psychotropic, hallucinogenic experience, one might see alien beings—and who knows what else.”

Hasson’s first ayahuasca-drinking experience in the summer of 2016 was unpleasant: “This cup was beyond vile… it was thick…like fibrous sediment. It reeked of something horrible and made me sick to my stomach.” But then he explains the psychotherapeutic benefits of this non-recreational drug; that it can

“connect you with dimensions that are beyond real and make you feel truths beyond truths. It focuses on things that are there, things that have escaped your attention, and it points flashing arrows at them.”

Hasson explains in his autobiography how “synaesthesia”is his “primary tool” in the workshops. He describes it as an act of empathy with each client, in which he takes on their belief system like a costume, and “since you are not them, their paradoxes become obvious.” Then he introduces them to “two contradictory parts of themselves.” This “paradox hunting” technique is based on the notion that people have deeply buried conflicts or contradictory beliefs, and only when they confront them are they able to make constructive choices.

Hasson’s method is to instruct his clients to find their “Intention” and to ask Grandmother (the Spirit of Ayahuasca) a question that would help identify the “paradoxes” (internal contradictions that cause cognitive dissonance in their memories and beliefs). He would then show them that they have a full choice over their lives and their personas and help them create a “One-Year Plan” as a route to the final goal, Happiness.

One might ask what Hasson has gained from his quest. His achievement is expressed in psychological terms as, “a clear and intuitive path to attaining a destiny of happiness.” He elaborates: “I was no longer willing to be blackmailed and terrorized by my own psyche.” Instead, he chose a path of “eternally renewable conscious choice to… fully trust and believe in the attainability of continuous versus momentary happiness.

Hasson’s autobiography ends with a 53-page summary of his philosophy, his vision of the meaning of life, called “ChoiceOS” (Choice Operating System). He trivializes God as “the cleverest guy around,” and attacks the notion of enlightenment as “something disconnected from our corporeal existence.” He concludes: “Come on fellas, when are you going to see that our very humanity, our incredible range of choices, good and bad alike, are our very divinity?”

In 2012, Hasson started building TierraMitica on 74 hectares of purchased land 45 kilometers from Tarapoto. His purpose was to create a permanent home for the Mythic Voyage. In June 2012, the first Mythic Voyage was held on his land. Between March 2013 and September 2014 many Mythic Voyages were held. These were renamed “ChoiceOS” in 2018, after the use of ayahuasca was stopped and replaced by guided meditation techniques. According to Mikis, “these techniques provide many of the benefits of the ayahuasca experience, including inducing altered states, of consciousness in his clients, which facilitates introspection.”

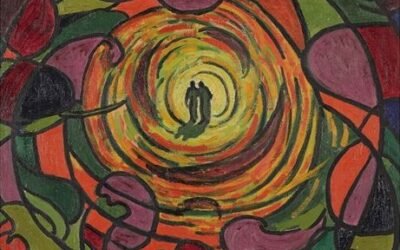

Between October 23 and 28, 2024, I interviewed all 14 members of the commune (two were away at the time). Some of the older members described joining Mikis on his Mythic Voyage up the Amazon River in the beautiful oak-paneled converted steamboat, disembarking at a lodge in the jungle forest. There, they would sit or lie on mattresses around a bonfire. Each would drink the cup of ayahuasca offered by a Shipibo maestra. Some got sick with vomiting and diarrhea, a few descended into Inferno, others saw beatific visions, and one felt nothing. The later Argonauts described the post-2018 ChoiceOS workshops held on the “mythic land” of TierraMitica, and they claimed the guided meditation techniques which had replaced the ayahuasca experience were equally effective.

All my informants were deeply impressed by Mikis’ uncanny skill as a psychotherapist. They explained to me that, because Mikis was autistic, he possessed a laser-sharp focus and an extraordinary gift for “reading” people. With fiery concentration he could note the tiniest flicker of a facial muscle or twitch of an eyelid, and signs of self-deception in a tone of voice or choice of words.

The members of TierraMitica all started out as “Argonauts” (participants in the Mythic Voyage/ChoiceOS). They had signed up for Hasson’s workshops in the hope of resolving childhood traumas, internal conflicts, and other issues. One man was devastated by his brother’s suicide, a successful actress was disappointed in her dream to forge a creative community of actors. One woman had just broken up with her lesbian lover. Several were concerned about self-destructive patterns that inhibited their careers or undermined their relationships. Some felt burned out and trapped in well-paid but very demanding careers that left no time for personal development or family.

They spoke about how Mikis’ therapy had helped them to forgive and reconcile with parents, cope with alcoholism and drug abuse, enhance their creativity, learn how to handle their bosses, and helped them choose their life partners. I found many of their stories touching and inspiring. They spoke about their search for a community where they could be open and honest with other people, and how in TierraMitica they felt a deep respect for each other and were united by a common understanding of how to achieve and maintain happiness.

Susan J. Palmer is an Affiliate Professor in the Religions and Cultures Department at Concordia University in Montreal. She has directed the Children on Sectarian Religions and State Control project at McGill University, supported by the Social Sciences and the Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC). She is the author of fourteen books, notably The New Heretics of France (Oxford University Press, 2012).