“The Mother of All Religions,” a tour de force on the sources of Theosophy’s foundational texts, is both impressive and irritating.

by Massimo Introvigne

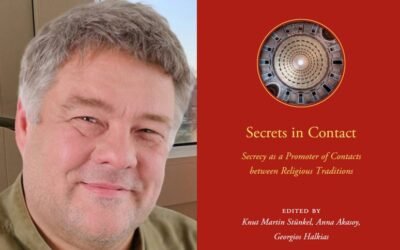

Urs App’s “The Mother of All Religions: The Genesis of Blavatsky’s Theosophy. Ancient Theology, Orientalism, and Buddhism” (Wil and Paris: UniversityMedia, 2025) is a book that arrives with the force of a scholarly thunderclap—and the tact of a bull in a metaphysical china shop. It is, at once, a meticulous reconstruction of Helena Petrovna Blavatsky’s literary career and a gleeful autopsy of her intellectual credibility. Admirable? Absolutely. Irritating? Frequently.

App’s achievement is staggering. He has done what no one else dared: traced, chronologically and obsessively, every book, article, and letter Blavatsky ever wrote, cross-referencing them with the sources she borrowed from—often without acknowledgment, occasionally without understanding. The result is a forensic map of Theosophy’s textual DNA, claiming that Blavatsky’s spiritual edifice was built not on Himalayan revelations but on a library of 19th-century curiosities, spiritualist pamphlets, and Orientalist misfires.

Some of these sources are familiar—Allan Kardec, for instance, whose influence on Blavatsky’s early spiritualism, appropriately, elevates. Others are more obscure, like Godfrey Higgins, whose obsession with a primordial religion becomes, in App’s telling, Blavatsky’s own idée fixe. She called it “Budhism with one d,” “the mother of all religions,” a mythical ur-faith predating historical Buddhism, corrupted by priests and institutions, and glimpsed only through the foggy lens of esoteric speculation. It was, for Blavatsky, the mother of all religions. For App, it was the mother of all misreadings.

But App is not content to merely list sources. He animates them. Louis Jacolliot, the flamboyant fraudster; Heinrich August Jäschke, whose Tibetan dictionary became Blavatsky’s linguistic crutch and sometimes comic foil; and a parade of Orientalists whose reputations have faded but whose fingerprints remain on Theosophy’s sacred texts. App revives these characters with flair, showing how their ideas—sometimes brilliant, often bizarre—were repurposed by Blavatsky into a spiritual system that claimed to be ancient but was, in fact, aggressively modern.

App argues, with prosecutorial zeal, that not only did Blavatsky plagiarize, but so did the Mahatmas—the mysterious Oriental adepts who allegedly wrote letters to Theosophists. These letters, App insists, are riddled with errors about Hinduism and Buddhism, and borrow liberally from Western Orientalist literature. He believes the conclusion is inescapable. The Mahatmas were figments of Blavatsky’s imagination, dressed in robes and footnotes, and paraded as divine authorities in a grand act of spiritual theater.

This is where the irritation sets in. App’s scholarship is unimpeachable, but his tone is less so. He claims neutrality, but his narrative drips with judgment. Blavatsky is not just mistaken; she is deceptive. The Mahatmas are not just mythical; they are fraudulent. And Madame’s system is not just syncretic; it is intellectually bankrupt.

App is not a sociologist, and it shows. His approach to spiritual movements is refreshingly unromantic but occasionally naïve. He notes, for instance, that Blavatsky changed her teachings on reincarnation and other doctrines, and finds this embarrassing for someone claiming to transmit “ancient wisdom.” But most believers in a “prisca theologia” would tell him that doctrinal evolution is not a bug—it’s a feature. They believe in eternal truths but accept that human understanding of them is mutable, fallible, and often contradictory. Assuming Blavatsky wrote the Mahatma letters herself, one of them—signed by Master Koot Hoomi to Allan O. Hume in 1882—offers a self-deprecating explanation: “the habitual disorder in which H.P.B.’s mental furniture is kept.” App quotes this approvingly, but may have missed its irony.

App also cites an ex-Theosophist who claimed that the whole Theosophical enterprise collapses if the Mahatmas are a myth. But this is a misunderstanding of myth itself. Religions are built on mythic narratives that are not falsifiable in the scientific sense. Myths are not “lies,” they are the architecture of belief. Christianity survived centuries of biblical criticism. Mormonism shrugged off the revelation that Joseph Smith’s “Book of Abraham” was translated from a funerary papyrus with no mention of Abraham. Believers simply recalibrated: if Smith was divinely inspired, then any text—even a grocery list—could trigger revelation relevant and valuable for the religious community.

Blavatsky anticipated this line of defense. In her final work, “The Key to Theosophy,” she wrote: “What does it matter whether they [the Mahatmas] do exist or not?… If the knowledge supposed to have been imparted by them is good intrinsically… why should there be such a hullabaloo made over that question?” App quotes this, but seems unconvinced. He reads it as a sly endorsement of the old chestnut that the end justifies the means. But perhaps she was ahead of her time—intuiting, a century before the sociologists caught up, that in the spiritual bazaar of modernity, it’s not the most verifiable myth that wins, but the one that sings loudest to the soul.

This brings us to a crucial distinction, one elegantly articulated for Catholics in the Pontifical Biblical Commission’s 1993 document, “The Interpretation of the Bible in the Church.” It separates exegesis—the historical-critical analysis of texts—from hermeneutics, which explores the relationship between texts and their readers. Exegesis asks, “What did this mean then?” Hermeneutics asks, “What does this mean now?” App excels at the former but sidesteps the latter.

Drawing on Gadamer, the document reminds us of the hermeneutical paradigms of “Horizonverschmelzung”—the fusion of horizons between text and reader—and “Zugehörigkeit,” the sense of belonging that binds interpreters to their subject. App’s readers may miss this. They may mistake his demolition of Blavatsky’s sources for a refutation of her doctrine. But belief is not built on footnotes. It is built on resonance.

App’s book is a triumph of exegesis. It is indispensable for anyone studying Theosophy, Orientalism, or the intellectual history of modern spirituality. But it is not the final word. Without exegesis, hermeneutics may become just postmodern arbitrariness where anything goes. Without hermeneutics, exegesis risks becoming a museum of dead ideas. With hermeneutics, even flawed texts can become living scriptures.

Theosophy will survive App’s critique, just as it survived the Hodgson Report, the Coulomb affair, and a century of academic skepticism. Its followers will continue to read the Mahatma letters, meditate on “Budhism with one d,” and find meaning in the mythic architecture Blavatsky built. And scholars, thanks to App, will have a richer map of the literary terrain she traversed.

In the end, App’s book is not just about Blavatsky. It is about the porous boundary between scholarship and belief, between plagiarism and inspiration, between the mental furniture of a 19th-century mystic and the spiritual furnishings of her modern admirers. It is a book that demands to be read—and then reread, with critical distance and interpretive generosity.

If Theosophy teaches us anything, it’s that truth is rarely tidy. Sometimes, the messiest minds produce the most enduring myths.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.