The crucial Theosophical influence on the fathers of modern abstract art has been progressively rediscovered in recent years.

*Lecture given at Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Florence, on January 23, 2026, on the occasion of the exhibition “Carlo Adolfo Schlatter. Artist of the Spirit.” The links refer to thematic articles on the relationship of various artists with Theosophy.

Article 3 of 3. Read article 1 and article 2.

This lecture assumes follows a model reconstructing the relationship between the Theosophical Society and the visual arts through three stages: didactic, symbolic, and abstract. In the first two parts, we examined the didactic and symbolic stages.

As historian Tessel Bauduin has noted, the forms in the Theosophical classic “Thought-Forms” are not abstract, because they are presented as faithful representations of thoughts and emotions. And certainly, the influence of the book on abstract art has sometimes been exaggerated. It is true, however, that Theosophy played a catalytic role in the transition from symbolism to abstract art, as shown by the experiences of Čiurlionis and some Futurists.

We can also follow the transition from symbolism to abstraction in the career of the Czech painter František Kupka (1871–1957), who was interested in Theosophy and spiritualism and, in his youth, even worked as a professional medium.

Wassily Kandinsky (1866–1944) explored Theosophy for several years and attended Steiner’s lectures in Germany when the latter was still a member of the Theosophical Society. Of course, Theosophy was not his only source of inspiration. His own interests in alternative spiritualities and the occult were eclectic, and he was also inspired by Russian folklore and shamanism. However, Theosophy played a role in Kandinsky’s transition to abstraction (see his first abstract watercolor, from 1910), and traces of it can be found in his influential manifesto “The Spiritual in Art” (1912).

The Dutch painter Piet Mondrian (1872–1944) joined the Theosophical Society in 1909. He too made the transition, typical of Theosophical painters, from symbolism to abstraction. Mondrian created “Neoplasticism,” a form of abstraction that he described in 1922 as “theosophical art in the true sense of the word.”

Only recently, thanks to exhibitions in various countries, has Hilma af Klint (1862–1944) been recognized as an important European abstract artist. She lived in a small Swedish town and requested that her paintings not be exhibited until twenty years after her death. Hilma af Klint was a spiritualist who claimed to paint under the influence of spirits. But she had also studied Blavatsky. She met Steiner in 1908 and followed him when he founded the Anthroposophical Society.

Many of the Finnish, Swedish, Norwegian, and Icelandic symbolist and abstract artists were influenced by Theosophy, but it is worth mentioning in particular the Finnish Ilona Harima (1911–1986), who was admired by Hilma af Klint, because the Theosophical Society was the main cultural interest of her life, and the Swedish artist Iván Agueli (1869–1917), an anarchist, Sufi Muslim, and member of the Theosophical Society, known for converting the esotericist René Guénon (1886–1951) to Islam. A recent rediscovery in Finland is that of Aleksandra Ionowa (1899–1980), a remarkable but forgotten artist and passionate member of the Theosophical Society (in one of her sketches of Annie Besant’s visit to Finland in 1928, a Master appears floating in the air on the right).

We will focus here on Theosophy, as discussing the further influences of Anthroposophy would take us too far afield. This influence was important in architecture, but not only there. At least mention should be made of the German artist Joseph Beuys (1921–1986), who explicitly acknowledged his debt to Steiner despite the criticism this brought him in the left-wing political circles he frequented, where Anthroposophy was not popular.

Lawren Harris (1885–1970), the most famous Canadian painter of the 20th century, was a particularly active member of the Theosophical Society. He gathered around him in the Group of Seven and other initiatives artists who were either members – James Edward Hervey MacDonald (1873–1932) and Arthur Lismer (1885–1969) – or are in any case close to the Theosophical Society. Less well known is the influence of Christian Science on this circle: Harris and others had several members of this American religion in their own families.

In 1927, Harris met Emily Carr (1871–1945) and used his influence to transform this semi-unknown artist from British Columbia into an international celebrity. Harris also tried to convert Carr to Theosophy. Under Harris’s guidance, the painter began to seriously study Theosophical doctrines, and traces of this can be seen in paintings such as “Grey” (1930). In the end, however, Emily wanted to remain a Christian. In 1934, she repudiated Theosophy and even burned her copy of Blavatsky’s “The Key to Theosophy.” But she remained friends with Harris.

In the 1930s, Harris concluded that true “Theosophical art” could only be abstract. From 1938 to 1940, he lived in New Mexico, where he founded the Transcendental Painting Group with other Theosophical artists, including the Hungarian-born American Emil Bisttram (1895–1976), Raymond Jonson (1891–1982), and French astrologer and painter Dane Rudhyar (pseudonym of Daniel Chennevière, 1895–1985).

Bisttram was the first to speak of a “New Age,” an era of happiness and peace that was to come. He created encaustic paintings, which he forbade from being sold during his lifetime, that were more than works of art and which he considered “portals” for entering the New Age.

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887–1986), who had already encountered Theosophy through her friendship with the Theosophist architect Claude Bragdon (1866–1946), an important author on the notion of the fourth dimension of space, visited the Transcendental Painting Group and later moved to New Mexico. Through another friendship, with the novelist Jean Toomer (1894–1967), O’Keeffe also became acquainted with the esoteric ideas of Pyotr Ouspensky (1878–1947) and George Ivanovich Gurdjieff (1866–1949).

Several New Mexico “transcendentalists,” including Bisttram and Jonson, were followers of the Russian painter Nicholas Roerich (1874–1947), a theosophist whose wife, Helena (1879–1955), claimed to receive messages from the Masters. This led to a further theosophical schism, Agni Yoga.

Bisttram had met Roerich in New York in the artistic circle created by Eva Palmer Sikelianos (1874–1952), the wife of the Greek poet Angelos Sikelianos (1884–1951), as the American branch of the Delphic Movement founded by the Sikelianos in Greece, and nicknamed “the Ashram,” where various theosophists gathered and where Besant herself gave lectures. The Mexican painter José Clemente Orozco (1883–1949) frequented the Ashram in New York and there he learned about Theosophy. With the financial help of the Guggenheim Foundation, Bisttram went to Mexico to study with the famous Diego Rivera (1886–1957), who was himself involved in the complex affair of the Mexican Rosicrucian movements. The work of these artists also fits into the cultural project of José Vasconcelos (1882–1959), Mexico’s Minister of Education in the 1920s, who promoted Theosophy as an alternative to both Catholicism and Marxist materialism and atheism.

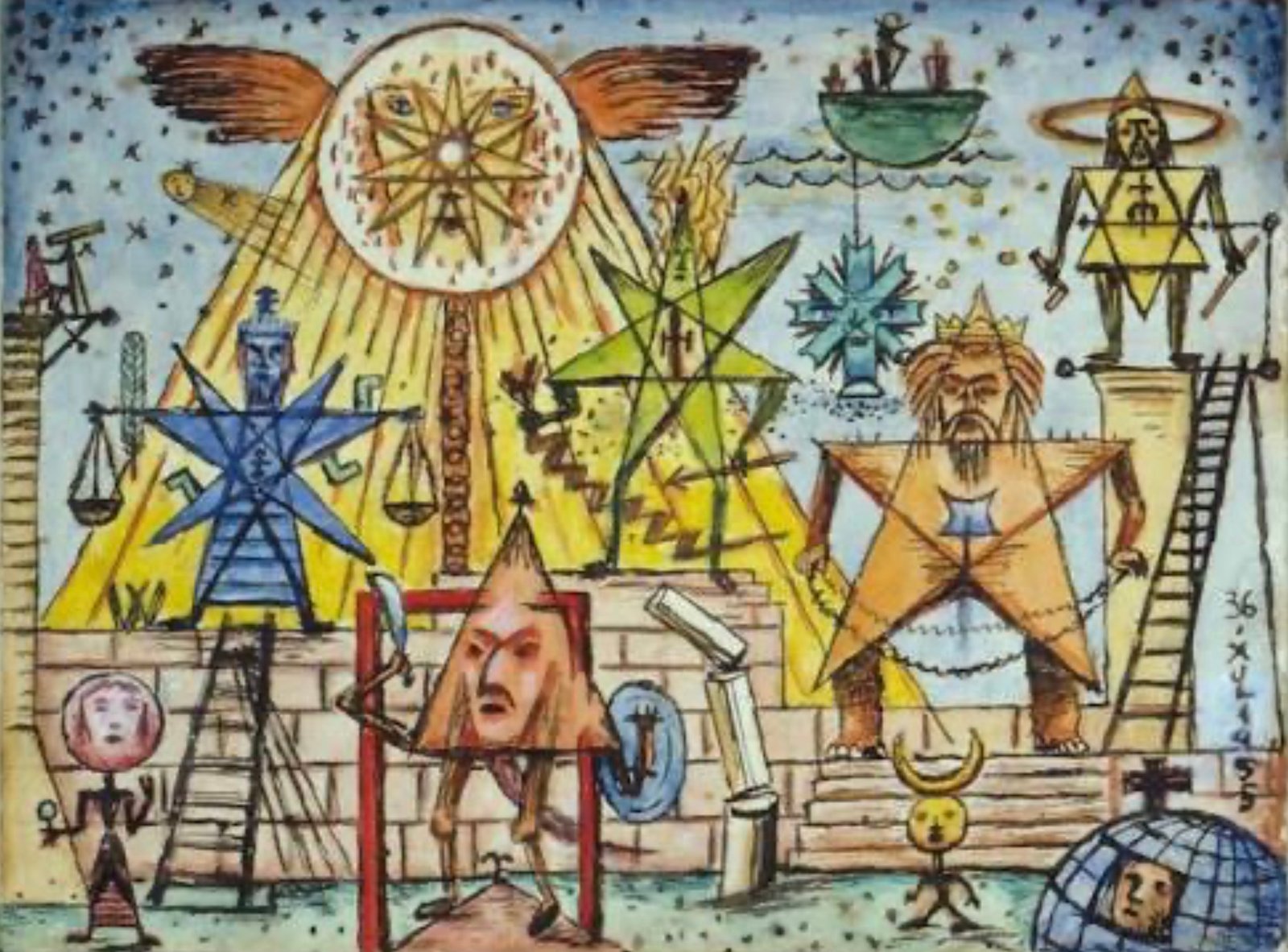

Among other Ibero-American artists influenced by Theosophy, Xul Solar (pseudonym of Oscar Agustín Alejandro Schulz Solari, 1887–1963), an Argentine member of the circle of writer Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986), is worth mentioning. Solar’s notes confirm his interest in Theosophy and Anthroposophy, although the major esoteric elements in his work derive from his friendship in the 1920s with the English occultist Aleister Crowley (1875–1947), who called Solar “the best seer I have ever tested” and asked him to paint a cycle inspired by the Chinese divination book “I Ching.”

Jackson Pollock (1912–1956) was introduced to Theosophy in high school by his art teacher Frederic John de St. Vrain Schwankowsky (1885–1974), a member of the Theosophical Society and the Liberal Catholic Church, through whom he participated in a retreat with Krishnamurti in Ojai, California. As an adult, Pollock lost his enthusiasm for Krishnamurti, but later returned to his interest in occultism and Theosophy through his friendship with the painter John Graham (1881–1961). Pollock’s formula, “abstract expressionism,” was adopted by Harris and became popular among Theosophist painters.

Theosophy also influenced modern art through personalities whose main activity was supporting artists and organizing exhibitions. An important figure in the Theosophical milieu was Hilla Rebay (1890–1967), Solomon Guggenheim’s (1861–1949) first collaborator in his activities as a patron and collector. It was Rebay who persuaded the magnate to collect abstract art and to entrust Frank Lloyd Wright (1867–1959) – an architect associated with Gurdjieff and Ouspensky – with the design of what is now the Guggenheim Museum in New York. No less influential – nor less close to the Theosophical circles – was Katherine Dreier (1877–1952). A patron and artist, through her Société Anonyme, she played a crucial role in bringing artists linked to the Theosophical world, including Kandinsky and Harris, to international attention.

Dreier also played a decisive role in promoting the art of Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968). Duchamp declared himself an atheist, but he was familiar with Theosophical doctrines through Ouspensky. An important part of his artistic research—including his seminal work “The Large Glass”—focused on the search for a fourth dimension in space.

But does a “Theosophical art” really exist? Or are there only artists who had some contact with the Theosophical Society? Perhaps the most articulate response to this question from the Theosophical side can be found in the writings of Lawren Harris. The Canadian artist argues that Blavatsky’s work makes possible a new aesthetic in which art no longer has to “preach” a religion or spirituality, as much Christian art did: neither directly nor through symbols.

A true “Theosophical art,” Harris concludes, must rather elevate the viewer and the artist to a higher plane of being through beauty. In theory, different art forms can achieve this effect. In practice, at this stage of human evolution, Harris believed abstract art was more effective.

American sociologist Howard S. Becker, as part of his important contribution to the sociology of art, argues that art is a social construct produced by “art worlds” in which the artist is never alone and the work is always co-produced with other social actors.,The Theosophical Society, with its particular interest in art, emerged as one of these social actors and contributed to the production of one or more specific “art worlds.”

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.