“Symbolism” offered to artists willing to express Theosophical ideas the language they were looking for.

Massimo Introvigne*

*Lecture given at Palazzo Medici-Riccardi, Florence, on January 23, 2026, on the occasion of the exhibition “Carlo Adolfo Schlatter. Artist of the Spirit.” The links refer to thematic articles on the relationship of various artists with Theosophy.

Article 2 of 3. Read article 1.

The scheme of this lecture assumes that the relationship between the Theosophical Society and the visual arts went through three stages: didactic, symbolic, and abstract. In the first part, we examined the didactic stage.

Symbolism (now a contested category) offered Theosophy the possibility of a second artistic style, with explicit Theosophical symbols that became acceptable to the general public. During Blavatsky’s lifetime, the great Victorian painter George Frederic Watts (1817–1904) became interested in Theosophy. It was Watts who first told the Pre-Raphaelite painter Sir Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898) about Theosophy. Several Pre-Raphaelites were interested in spiritualism and the occult, and naturally extended their metaphysical explorations to Theosophy.

The second, symbolist phase of a “Theosophical art” emerged in Belgium around Jean Delville (1867–1952), who was part of the circle that organized the first Belgian meetings of the Theosophical Society. Various artists moved in Delville’s Theosophical circle, including the greatest Belgian painter of the time, Fernand Khnopff (1858–1921). The influence of the Belgian Theosophical symbolists was felt in France, especially on the Nabis group, whose leader, Paul Sérusier (1864–1927), was a member of the Theosophical Society. Paul Gauguin (1848–1903) was also a reader of Blavatsky’s “The Secret Doctrine.” The Belgian Theosophist artists collaborated with the English poet Clifford Bax (1886–1962) and other English members of the Artistic Section of the Theosophical Society.

In Poland, one of the leading Symbolist painters, Kazimierz Stabrowski (1869–1929), founded the Theosophical Society of Warsaw, the first nucleus of the Polish Theosophical Society. Later, he followed Steiner into the Anthroposophical Society. Stabrowski directed the Warsaw School of Fine Arts and invited his most gifted students to attend evenings where he spoke about Theosophy, spiritualism, and Eastern religions.

Among these students was Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis (1875–1911), the Lithuanian painter and composer who died at the age of 35 after helping to initiate the European transition from symbolism to abstract art. Čiurlionis was not a member of the Theosophical Society but attended Stabrowski’s THeosophical evenings and systematically read the works of Camille Flammarion (1842–1925), a French astronomer and prominent member of the Theosophical Society.

In Lithuania, Liudas Truikys (1904–1987) is also worth mentioning. He was a clandestine follower of Theosophy, which was banned during the Soviet era, and even managed to hide an altar dedicated to the Masters in his home.

A decisive figure in the artistic and political history of Central America is the Spanish painter, naturalized Costa Rican, Tomás Povedano de Arcos (1847–1943), who was very close to Krishnamurti and was the founder of the Theosophical Society in Costa Rica.

French-language symbolism was influenced by Édouard Schuré (1841–1929), author of “Les Grands Initiés” (1889), a critical member of the Theosophical Society, and later a collaborator of Steiner. Filippo Tommaso Marinetti (1876–1944), the Italian poet and founder of Futurism, considered his meeting with Schuré in early 20th-century Paris to be crucial fir his artistic choices. Several Italian Futurists had contacts with the Theosophical Society. Among them were Giacomo Balla (1871–1958), the Ginanni Corradini brothers, Bruno Corra (1892–1976) and Arnaldo Ginna (1890–1982), and Umberto Boccioni (1882–1916). The register of the Theosophical Society in Adyar contains evidence of Ginna’s (“Corradini Arnaldo Ginanni”) enrollment in the Bologna lodge on February 19, 1913.

Boccioni was among the painters who acknowledge their debt to Besant and Leadbeater’s book “Thought-Forms” (1905). Boccioni stated that, as emerges from his two cycles “Stati d’animo” (Moods), he was inspired by the idea in the book that thoughts and feelings have shapes and colors that a clairvoyant eye can see.

Sounds also have shapes and colors in “Thought-Forms.” The idea of synesthesia, which combines music and painting, is not new, but the book inspires several artists, including the futurist Luigi Russolo (1885–1947).

The influence of Theosophy on Italian artists is not limited to Futurism. In Livorno, the Belgian painter Charles Doudelet (1861–1938) organized Theosophical meetings in his villa, which influenced many Tuscan artists of the time. Filippo De Pisis (1896–1956) was so immersed in Theosophy that his sister, also a Theosophist, even considered him a Bodhisattva.

Membership in the Theosophical Society was decisive in Bohemia for the disturbing art of Josef Váchal (1884–1969), known for his frescoes of angels and demons, as were theological influences in Slovakia for László Mednyánszky (1852–1919), a national painter who was long censored for his frank celebration of homosexuality.

Leadbeater moved to Australia in 1915 and made Sydney a theosophical center of international importance. Along with “Thought-Forms,” another book that became popular among Australian Theosophists was “New Science of Color” by Beatrice Irwin (1888–1956), an English missionary of the Bahá’í faith who was also interested in Theosophy.

Two of the most important Australian painters of the 20th century, Roy De Maistre (pseudonym of Leroy de Mestre, 1894–1968) and Grace Cossington Smith (1892–1984), were influenced by Leadbeater and Irwin, and in particular by “Thought-Forms.” De Maistre co-organized the controversial 1919 exhibition in Sydney, “Colour in Art,” and even managed to patent and sell a “Colour Harmonising Chart” based on the correspondence between colors, musical notes, and emotions and inspired by “Thought-Forms.”

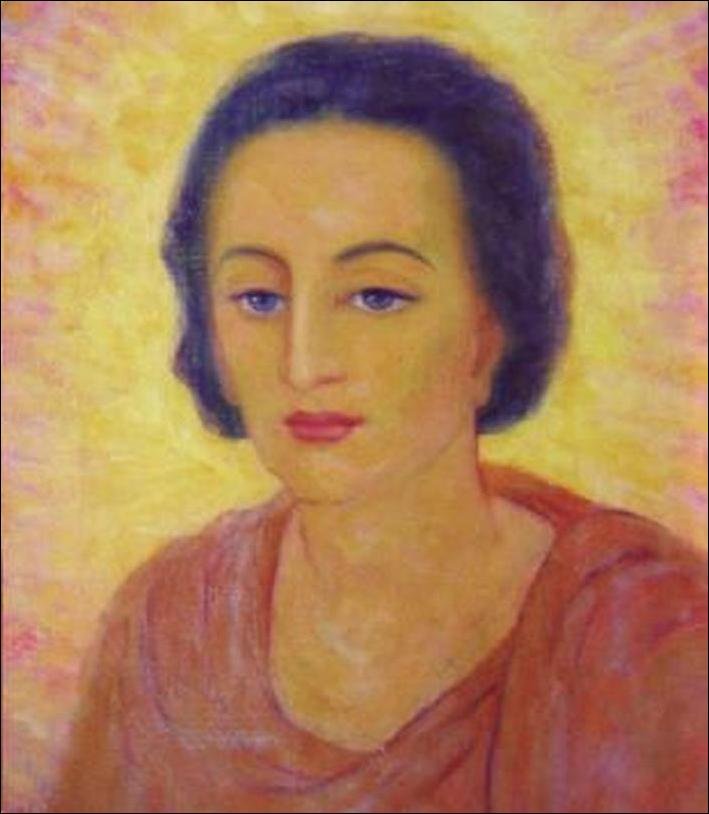

Florence Ada Fuller (1867-1946), Australia’s leading painter, had a mysterious and tragic encounter with Leadbeater and Theosophy. An enthusiastic member of the Theosophical Society, Leadbeater guided her in painting the Masters through clairvoyant visions—only the portrait of the Buddha was made public—which shook her so deeply that she spent the last twenty years of her life in a psychiatric hospital.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.