Three decades ago, a physical genocide was committed in the heart of Europe amid international indifference. In China, a cultural genocide is still being perpetrated amid the same international indifference.

by Marco Respinti*

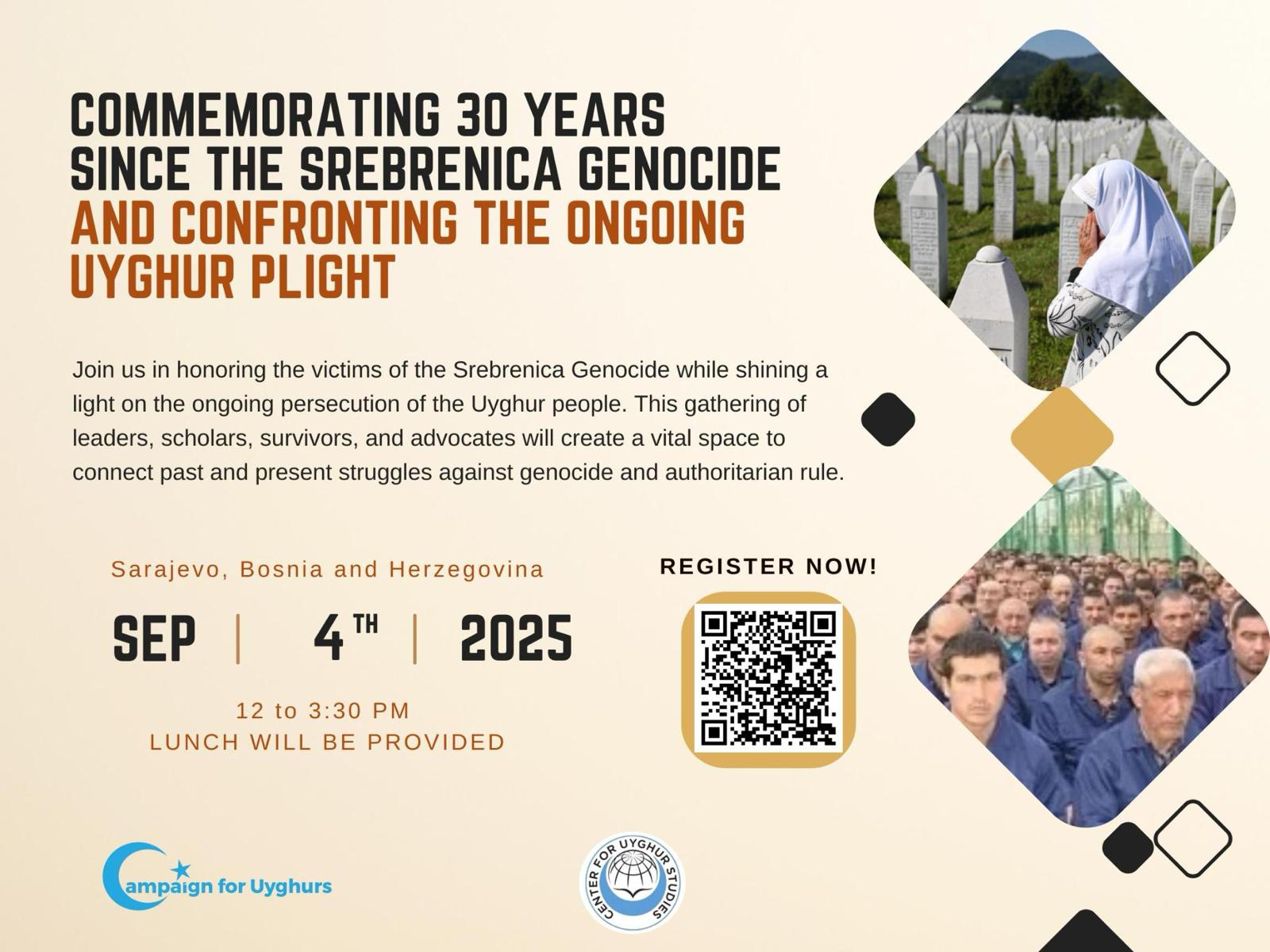

*Full version of a paper presented in a shortened version at the conference “Commemorating 30 Years Since the Srebrenica Genocide and Confronting the Ongoing Uyghur Plight,” hosted in Sarajevo, capital city of Bosnia-Herzegovina, by the Center for Uyghur Studies and Campaign for Uyghurs on September 4, 2025.

Thirty years ago, in July 1995, the world witnessed the most horrendous mass murder ever to happen in Europe after World War II. That horrendous massacre was a genocide: the genocide of the Muslim people of Srebrenica and Žepa. It happened during the Bosnian War (1992–1995) in Bosnia-Herzegovina. This was the third war that tore apart the territories which had once composed Yugoslavia, officially called the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, a socialist federal state under Communist rule.

It should be immediately noted that the use of the adjective “federal” in the official name of that state was mere window dressing—just as was its supposedly non-aligned role in the confrontation between the Soviet bloc and Western democracies. In that case, “federalism” did not mean “decentralization,” but rather a federation of local centralisms. As for Yugoslavia’s fictional “third position”—which tried to present itself as a different kind of Communism while remaining thoroughly Communist—it in fact served to surreptitiously draw neutral countries into the sphere of influence of the Soviet bloc, acting as a strategic proxy.

In 1992, following the demolition of the Berlin Wall and the disintegration of the Soviet bloc, Yugoslavia also disintegrated when half of its six republics—Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina—proclaimed independence. In all three cases, what remained of the Yugoslav state attempted to suffocate independence through a war of aggression. The three wars that resulted were the final attempt of disintegrating Communist Yugoslavia to maintain its totalitarian rule over those territories and their peoples.

But a nationalistic element was added to those Communist wars of aggression. What remained of Communist Yugoslavia—much reduced in territory after the proclamation of independence by Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina—was in practice limited to Serbia and Montenegro, the latter always strictly controlled by the former, while Macedonia, the sixth Yugoslav republic, remained more or less in the background.

It had always been so, even under Communist rule. Serbs have always controlled Communist Yugoslavia: in spite of the fact that the Communist tyrant of Yugoslavia, Josip Broz (1892–1980), commonly known as “Tito,” was a Croat, the top-level nomenklatura was heavily dominated by Serbs. Both Titoist Yugoslavia and the three wars of aggression against independent Slovenia, Croatia, and Bosnia-Herzegovina were examples of Communism in action with a nationalist flavor. By allying with chauvinistic Serbian elements of non-Communist origin, lured by the nationalist character of those three wars of aggression, the last attempt to impose Yugoslav rule on three independent countries can well be described as a national-communist effort—or, in other equivalent terms, yet another national-socialist attempt in the heart of Europe.

This affirmation, sustained by facts and by the intrinsic socialist as well as nationalist character of Yugoslavia before and after 1992, should not be construed as an attempt to reduce everything to Nazism, as if Nazism were the only face of evil. On the contrary, it should be considered—at least this is my intention—as a humble contribution to the proper characterization of Communism: despite the internationalist rhetoric of Maxism-Leninism, all Communist regimes have always played the nationalist card as well. Sometimes this happened openly, sometimes more subtly, but it always happened—in the Soviet Union, in Eastern Europe, in Indochina, and in the People’s Republic of China (PRC). This is, de facto, one of the underlying reasons supporting the historic resolution passed by the European Parliament on September 19, 2019, which equates the criminality of Nazism and Communism.

In the PRC, it not only happened in the past; it is still happening, since Communism there is well alive and kicking, and the regime displays all its national-communist characteristics by singling out distinctive ethnic groups, called “minorities,” for persecution.

In July 1995, the national-communist aggression by the post-1992 Yugoslav state cost the lives of more than 8,000 people. They were Bosniaks, the distinctive name used to indicate Bosnian Muslims—southern Slavs native to Bosnia who, over the centuries, had adhered to Islam and who should not be confused with “Bosnians,” a term that designates any citizen of Bosnia-Herzegovina, regardless of ethnicity or religion.

The genocide of Bosniaks perpetrated by the national-communist post-1992 Yugoslav state was driven by both nationalist and Communist ideology. It was an attempt to punish and reconquer an entire people who dared to set themselves apart from the socialist “paradise” of Yugoslavia in order to affirm their own cultural identity. The combination of these two factors pushed the post-1992 Yugoslav state to envision the complete eradication of the Bosniaks, and Srebrenica became, so to speak, the showcase of that criminal attempt.

Genocide, as we all know, is not a mere synonym of massacre. It is a distinct criminal offense: the deliberate attempt to completely wipe out a human group, as defined by the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide.

In 1993, the UN Security Council established the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia to prosecute perpetrators. On April 19, 2004, the Tribunal published its final judgment against General Radislav Krstić of the Army of Republika Srpska, the self-proclaimed Serb secessionist republic within independent Bosnia and Herzegovina, formally recognizing the massacre that took place in Srebrenica as an act of genocide.

I already mentioned the PRC and its national-communist persecution of ethnicities. Ethnic groups in the PRC are persecuted because they do not accept the totalitarian rule of the Chinese Communist regime, holding dear their cultural identity, language, customs, and religion. The case of the people living in East Turkistan—as its non-Han inhabitants call the region that the regime refers to as Xinjiang—is blatant.

The majority of them belong to the Uyghur ethnicity, with significant elements of other Turkic peoples, and most of them are Muslim. Their identity as a people, and their unwillingness to comply with the ideological and atheistic rules established by the national-communist regime of China, is sufficient to subject them to all sorts of injustice and violence: unlawful arrests and deportations, imprisonment in labor camps, indoctrination in re-education camps, immoral violations of the sanctity of their households and families, torture, segregation, rapes, and even suspicious deaths in custody occur on a daily basis. Uyghurs are also subjected to the brutal practice of forced organ harvesting.

The parallel between Srebrenica and the fate of the Uyghur people is evident.

In both cases, the totalitarian regime, considering ethnicities, cultural identities, and religions its number one enemies, represses innocent people by committing all sorts of misdeeds. Yet another decisive element links the Bosniaks of Srebrenica to the Uyghurs: both tragedies stand as a glaring and unforgivable failure of the United Nations, a betrayal of its very mandate to protect the innocent and defend the oppressed.

Srebrenica was made possible by the passivity and distraction of the UN peacekeeping forces on the ground. Before the massacre, Srebrenica—already besieged—had been declared a “safe area” by the United Nations and placed under its direct protection. This is why a large number of Bosniaks, fleeing from other devastated areas of the country, gathered in the town. To defend Srebrenica, a UN Protection Force was deployed: 370 lightly armed Dutch soldiers, who proved utterly ineffective. Worse still, on July 13, they handed over some 5,000 Muslims who had sought refuge in the Dutch base, in exchange for the release of 14 Dutch peacekeepers held by the Bosnian Serbs, as later demonstrated and confirmed by courts of law.

One may even wonder whether something more was at play, when one reads what was written on the wall of a military barrack in Potočari (7 km from Srebrenica) by an unknown Dutch soldier: “No teeth…? A mustache…? Smel [sic] like shit…? Bosnian Girl!” The Bosnian artist Šejla Kamerić later used this sentence in 2003 to create a powerful piece of denunciation art, significantly titled “Bosnian Girl.”

Both the case of Srebrenica and that of the Uyghurs were—and still are—surrounded by international indifference. Everybody knows, everybody talks, nobody acts, nothing changes.

One may object that Srebrenica was a horrible massacre, while the fate of the Uyghurs is less bloody. This would be a mistake. Srebrenica was a case of physical genocide; the Uyghur case is instead an example of cultural genocide—a genocide perpetrated slowly over the years, hence also referred to as “a cold genocide.” If it is not stopped now, it will continue day by day, erasing every distinctive element of Uyghur identity until the final day arrives: the day when the Uyghur people will exist no more, the day of a slowly consummated Uyghur Srebrenica.

Marco Respinti is an Italian professional journalist, member of the International Federation of Journalists (IFJ), author, translator, and lecturer. He has contributed and contributes to several journals and magazines both in print and online, both in Italy and abroad. Author of books and chapter in books, he has translated and/or edited works by, among others, Edmund Burke, Charles Dickens, T.S. Eliot, Russell Kirk, J.R.R. Tolkien, Régine Pernoud and Gustave Thibon. A Senior fellow at the Russell Kirk Center for Cultural Renewal (a non-partisan, non-profit U.S. educational organization based in Mecosta, Michigan), he is also a founding member as well as a member of the Advisory Council of the Center for European Renewal (a non-profit, non-partisan pan-European educational organization based in The Hague, The Netherlands). A member of the Advisory Council of the European Federation for Freedom of Belief, in December 2022, the Universal Peace Federation bestowed on him, among others, the title of Ambassador of Peace. From February 2018 to December 2022, he has been the Editor-in-Chief of International Family News. He serves as Director-in-Charge of the academic publication The Journal of CESNUR and Bitter Winter: A Magazine on Religious Liberty and Human Rights.