Voltaire presented the Benedictine scholar, who wrote about vampires, as gullible. In reality over the years his positions went from dubious to skeptical.

Massimo Introvigne*

*A paper presented at the Occult Convention 2024, organized by the Società dello Zolfo, Parma, September 7, 2024

Article 4 of 5. Read article 1, article 2, and article 3.

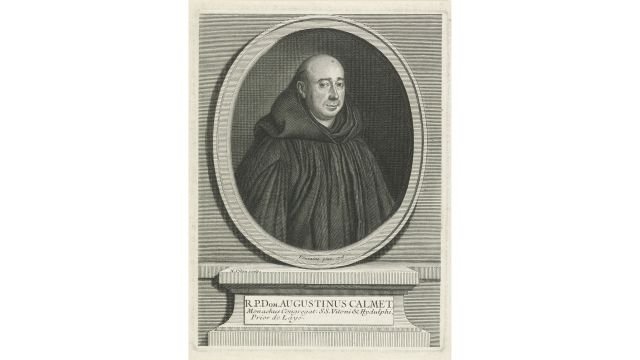

My statement that the Catholic Church in the 18th century embraced the skeptical position in the debate about vampires (partly because it wanted to exclude the esoteric one) may be questioned by those who have read Voltaire’s pages on the most famous Catholic theologian of that century who dealt with vampires, the Benedictine Dom Augustin Calmet. The Enlightenment philosopher portrayed him as a gullible true believer in vampires. However, we should not take Voltaire’s ironic criticism at face value and read Calmet directly.

First of all, Calmet was not a country friar. He was a famous theologian and that is why Voltaire visited him in the first place. His monumental biblical “Commentary” reached twenty-six volumes. He was also not particularly conservative: King Louis XIV had to personally intervene to defend him against accusations of Jansenism. He was praised by both Pope Benedict XIV and Empress Maria Theresa (both skeptical of beliefs in vampires). In 1718, he became abbot of Saint-Leopold in Nancy and in 1728, prior of the important monastery of Senones. He directed the latter for thirty years, enriching its library, continuing to write numerous volumes, and even refusing an appointment as bishop, to which he preferred the calm of his abbey.

Today—largely because of Voltaire—Calmet is remembered almost only for a work of 1746, which he considered minor and which instead ended up being his most widely read. It was the “Dissertations sur les apparitions,” renamed on the occasion of its considerably modified third edition of 1751 “Traité sur les apparitions,” which also mentions vampires in its subtitle.

It is important to note that for a couple of hundred pages what Calmet offers is, properly speaking, an anthology of rarely commented excerpts drawn from earlier sources on vampires by both skeptics and believers. To attribute to Calmet, as is often still the case today, this or that chapter of his work, which merely reproduces an earlier writing, is to fail to have a good understanding of the compilatory method that enabled many eighteenth-century scholars to publish such a large number of volumes in a few years.

Of decisive importance in order not to take Voltaire’s criticisms, inspired by his well-known anticlericalism, at face value, is the comparison between the 1746 and the 1751 editions of Calmet’s text. As Italian scholar Nadia Minerva writes, “critics—and not only those of the eighteenth century—have almost exclusively referred to the first edition, forgetting to emphasize the Benedictine’s self-critical efforts and the profound changes the subject of vampires underwent in the 1751 edition.” Not only had Calmet read the critical reviews, but “a comparison of the two main editions shows that he took them decisively into account.”

Only after the anthology part, Calmet moves on to explain what he believes should be thought of vampires. He premises that the devil certainly cannot raise the dead, and can molest or “animate” a corpse only in very rare circumstances, or perhaps never. The Benedictine first divides the explanations of vampirism advanced in the literature into five categories that read vampire phenomena respectively as miracles, as effects of a sick imagination, as equivocations (the alleged vampires are not really dead), as the work of the devil, or as natural phenomena attributed to animals or diseases.

Calmet states that all explanations assume that there is something to explain. But this is not proven. After reproducing the reports of the Austro-Hungarian gendarmes and physicians, already in the first edition Calmet comments: “I read and reread them, and to tell the truth I found in them no shadow of truth or even probability of what was being reported. And yet these documents are regarded in our country [France] as gospel.”

The alleged fact cannot be true, on the basis, Calmet states, mainly “of the objection founded on the impossibility of these vampires coming out of their graves and re-entering them without seeming to have moved the earth by going out or re-entering. This difficulty has never been solved and will never be answered. To claim that the devil makes thin and spiritualizes the bodies of the vampires is something proposed without proof and without verisimilitude.”

In the first edition a shadow of doubt remained: Calmet wrote that there are still demonic actions that we know nothing about. But in the second edition the conclusion is drastic and leaves no room for ambiguity: “I doubt that there is any other party to take in this matter than that of absolutely denying the return of the vampires.”

In the transition from the first to the second edition, the doubting formulas disappear, replaced by a harsh critique of both sources and demonological interpretations. If the devil has anything to do with vampires, it is only because he certainly loves to propagate disorder and superstition.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.