Antoine Faivre, the father of “vampire studies,” distinguished between Enlightenment-inspired, demonological, and “Paracelsian” positions.

Massimo Introvigne*

*A paper presented at the Occult Convention 2024, organized by the Società dello Zolfo, Parma, September 7, 2024

Article 3 of 5. Read article 1 and article 2.

The late Antoine Faivre is rightly recognized as the father of the academic discipline of “vampire studies.” According to the French scholar, these are not marginal curiosities but represent the last great academic debate on magic in European history.

Politely, Faivre frequently cited me and the American historian of religions J. Gordon Melton as part with him of a group of three scholars who gave academic dignity to the study of the vampire myth (as different from the study of the literary vampire by historians of literature). Faivre preceded me, however, by almost thirty years. My contribution to the field is primarily the theory that the vampire myth spreads to Protestant and Orthodox lands where the Catholic belief in Purgatory was lacking. The doctrine of Purgatory “settles” the dead not so good as to go to Heaven and not so bad as to go to Hell, without the need for them to wander the Earth as undead. There were no accounts of vampire incidents in Catholic Italy, France, or Spain.

Faivre distinguishes three positions: the rationalist, the theological, and the esoteric discourse, but each of the three actually has numerous variations.

Thus the rationalist discourse did not always and necessarily follow Zedler’s version, according to which visions of vampires are mere hallucinations. Professor Geelhausen believed, for example, that vampires were indeed bodies that came out of graves and appeared to the living. Only, they were not really dead but “false dead,” buried alive by mistake.

Still in Leipzig, in 1732, Johann Christoph Meinig, writing under the pseudonym “Putoneus,” and Johann Christoph Fritsch, who published his work anonymously, even more ingeniously resorted to animal diseases and in particular the rinderpest. As chance would have it, the disease had struck the very lands from which the vampire reports came in the first decades of the eighteenth century. If one consumes, these physicians observed, meat from cattle affected by the plague, a severe fever with hallucinations can ensue, explaining the vampire reports.

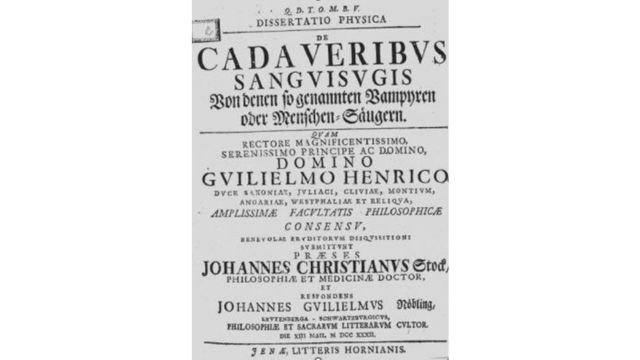

The theological discourse also went through several variations. One continued the demonological explanation. Johann Wilhelm Nöbling, who signed with the pseudonym “Johann Christoph Stock,” published, again in the fateful year 1732, a “Dissertatio physica de cadaveribus sanguisugis,” according to which the culprit for the vampire incidents could be the classic demon incubus or succubus known to the old demonologists. Others concluded that undoubtedly it must have been villages with particularly dissolute lives that God intended to punish by allowing the devil to be unleashed. The latter thesis would be taken up by Günther Hellmund in a 1737 work.

In 1738, Franciscus Solanus Monschmidt, in one of the few manuals for exorcists dealing with the subject, did not rule out that vampires were men and women who made a pact with the devil during their lifetime. To the barbaric practices of impalement and beheading, the pious exorcist suggested substituting exorcism, penance, and confession.

Not all church priests and pastors believed in vampires. Indeed, it was particularly in ecclesiastical circles that a skeptical line gradually prevailed. In Germany, in 1753, the preacher Johann Friedrich Weitenkampf returned to the explanation that vampires were not dead people at all, but living that had been buried prematurely.

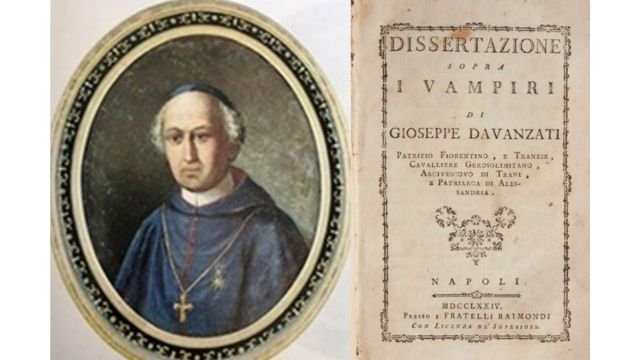

More importantly, between 1738 and 1743, Monsignor Giuseppe Antonio Davanzati, Archbishop of Trani who would become a cardinal, wrote a “Dissertation on Vampires.” He resolutely denied that vampires existed and attributed the evidence to superstitious and often alcoholic peasants. Davanzati wrote: “To unravel, and clear up this phenomenon there is no longer any need to have recourse to Heaven for miracles, nor to Hell for demons, nor on Earth to find the causes, nor much less is there any need to have recourse to Philosophers to consult their systems. The true cause of these appearances, he who yearns to find it will not be able to find it elsewhere than in himself, and outside himself he will never find it. The true and only cause of Vampires is our corrupt and depraved imagination.”

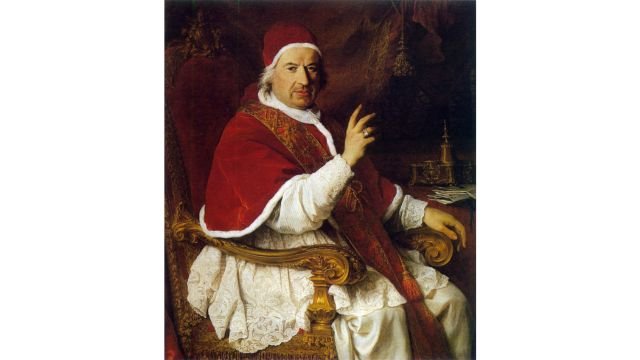

Benedict XIV (Prospero Lambertini), Pope from 1740 to 1785 and an admirer of Davanzati, stated in his classic work on beatifications and canonizations that beliefs about vampires “still today lack secure evidence and are considered, indeed, by the most reasonable people as fallacious fictions of the imagination.” As for the fact that corpses were found undecomposed, the Pontiff noted that eighteenth-century medicine now explained this by natural causes.

In 1794, citing his own treatise, Benedict XIV in a sternly worded letter to the Greek Catholic Prelate of Lviv stated that “it is above all up to you, as Archbishop, to eradicate these superstitions. You will discover, going back to the source, that there may be priests who accredit them in order to convince the people, naturally credulous, to pay them for exorcisms and masses.”

By the second half of the 18th century, the skeptical position, which saw vampires as a figment of the human imagination, had become official in the teachings of the Catholic Church.

Faivre saw in some of the treatises that appeared in Leipzig in 1732 a position that was not theological but esoteric. Faivre called the arguments of these authors “neo-Paracelsian,” related as they were to the magical qualities of the blood of corpses and the astral spirit. The underlying idea (which went back to Aristotle) was the division of the human being into four constituent parts: the nutritive soul, the sensitive soul, the rational soul, and the body. Crucial to explain vampirism was the thesis that the nutritive soul stays with the body for a certain period, and the sensitive soul stays there even longer, while the rational soul goes to Heaven or Hell (or is reincarnated).

Faivre wrote that according to the neo-Paracelsian esoteric perspective, the nutritive soul can behave as a “wandering vital spirit” that aspires to return to the World Soul (Anima Mundi). On its journey to this ultimate destination, it remains filled with the images with which the person’s spirit was imbued before death.

Faivre summarized this position as follows: “If the person has longed to become a vampire, it may be that she will indeed become one. Then the nutritive soul rises from the grave, and by a kind of contraction of the air procures a subtle, etheric body. While the corpse remains in the coffin—who would deny it? —the etheric body moves, it leaves to its familiar places, to people close to the deceased, whose blood it absorbs, then it returns to the corpse to inject it with the blood it has taken possession of. Indeed, for the vital spirit not to cease to exist (not to dissolve) it is necessary for the corpse not to rot. One can therefore understand why the victims believe they see the dead man himself in the course of the suction, when in fact they see only a ‘magical,’ astral image of him.”

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.