From Hong Xiuquan’s 1837 vision, a full-blown religion was born. Soon, it acquired an army and declared war to the Qing dynasty.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 3 of 5. Read article 1 and article 2.

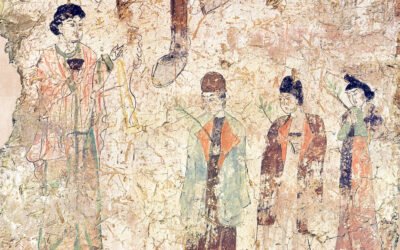

We saw in the previous article of this series how the 1837 vision, interpreted in 1843 through the lenses of Christian Chinese convert Liang Fa’s (1789–1855) Good Words to Admonish the Age, persuaded Hong Xiuquan (1814–1864) that he was God’s younger son. Like his elder brother Jesus, he was not God himself but had a divine mission. He was called to restore the worship of the One True God, Shangdi, who was both the Christian God and the God adored in China in the most ancient times, and eliminate the worship of the false demonic gods coming from the Buddhist and Taoist traditions.

China’s “Three Teachings” also included, alongside Buddhism and Taoism, Confucianism. Originally Hong, who had trained as a classical Confucian scholar, spoke highly of Confucius, and clearly his ethic teachings, emphasizing filial piety, chastity, and sobriety (with a strong prohibition against smoking opium and gambling) combined Confucianism with the Christian Ten Commandments. In later accounts of his visions, however, he remembered that he had seen Confucius punished in Heaven with lashes, since he had also spread teachings favoring the worship of gods other than the One True God. God had forgiven Confucius in the end, as his good deeds balanced the bad ones, but had prohibited him to descend again on earth forever.

Having understood what his vision meant, Hong felt called to found a religion. As it usually happens, his first converts were his relatives and neighbors, including cousin Hong Rengan (1822–1864), and best friend and distant cousin Feng Yunshan (1815–1852). Hong believed that to restore monotheism he should destroy the idols where the demons resided, and started organizing expeditions to local temples in Guangdong to smash Confucian tablets and Buddhist and Taoist statues. While he gathered followers, he also made powerful enemies among the local aristocrats, who financially supported the temples.

This persuaded Hong and Feng Yunshan to leave Guangdong and travel to Guiping county, Guangxi province, where Hong had relatives. As mentioned in the previous article, Hong and his relatives were Hakka, part of a Chinese ethnic minority, and they found new converts among the Hakka of Guangxi. It is true that the discriminated Hakka found relief in a message announcing that God’s younger son was one of them, although ethnic protest was never the main reason for the expansion of the new religion.

Rather, many who had found the Gospel preached by Western missionaries too distant from Chinese culture, were attracted by Hong’ “Sinicized” Christianity (a word used today with a different meaning). In Guangxi, Hong and Feng separated and somewhat lost track of each other. Feng remained there, where he organized a society of “God-Worshippers,” giving to those who had believed in Hong’s vision the first structure.

Hong returned to Guangdong and, together with his cousin Hong Rengan, in 1847 accepted an invitation by a flamboyant Baptist missionary from Tennessee, Issachar Jacox Roberts (1802–1871), to spend time with him in Canton. There, they discovered the Chinese translation of the Bible by German Lutheran missionary Karl Gützlaff (1803–1851) and his co-workers, which had an important influence on the Taiping. For reasons debated by historians, the two Hongs left Roberts before he had baptized them as he had promised, but remained in good relations with the American missionary for many years.

Hong Ziuquan then returned to Guanxi and, after an adventurous trip in which he was robbed by bandits, was finally reunited with Feng and learned he had organized the “God Worshippers.” Besides compiling theological writings, Hong and his followers resumed in Guanxi their old projects of smashing idols in the temples in the name of pure monotheism. They also acquired new followers, among whom were two Hakka from destitute families who later played an important role in the Taiping movement, Yang Xiuqing (1823?–1856) and Xiao Chaogui (1820–1852). While Hong and Feng were back in Guangdong, Yang and Xiao were recognized as the leaders as the God Worshippers in Guanxi, and both started transmitting messages from Heaven, with Yang channeling God the Father and Xiao channeling Jesus Christ. Their messages validated Hong’s vision, and Hong pronounced them genuine.

The God Worshippers were organizing themselves in Guanxi, but so were their enemies, who as it had happened in Guangdong did not tolerate Hong’s iconoclastic destruction of temple idols. Some God Worshippers were arrested, and two were tortured to death in jail in 1849. The incident persuaded Hong that a clash with the Manchu power was unavoidable. By 1850, he was actively acquiring gunpowder and weapons, and preparing for a military uprising.

Meanwhile, the Manchu empire in the same area of Guanxi was busy fighting bandits and river pirates, many of them members of the Heaven and Earth Society (Tiandihui), a secret society and the ancestor of the organized crime groups known today as the Triads, but at the same time a religious and political organization with a motto calling for “destroying the [Manchu] Qing and restoring the Ming.” Although never a member, Hong met Tiandihui leaders, and told them that destroying the Qing was a worthy program but restoring the Ming was impossible, and a new dynasty should replace the Manchu. As the founder of the new dynasty, Hong had in mind himself. Some Tiandihui members were persuaded, or told Hong so, but they proved difficult and unfaithful allies.

By 1850, Hong had thousand of followers and was a force to be reckoned with in Guanxi. He also emanated his most controversial edict, ordering men and women among his followers, including husbands and wives, to live separately, meet if needed by remaining a few steps apart from each other, and totally avoid sexual intercourse, under penalty of punishments administered by Hong’s militias that might go up to the death penalty. As a counterpart to this harsh precept, women were offered the possibility to serve in positions equal to men in the bureaucracy Hong’s religion was building, and as military in its militias.

At the end of 1850, skirmishes with Qing troops who tried to seize Jintian, a town today part of the prefecture-level city Guiping, which was under the control of Hong’s followers who administered it independently from the official authorities, escalated to a war. On January 11, 1851, Hong declared formally that he was in a state of armed revolt after the Qing. It was the Jintian Uprising, that we saw praised and solemnly commemorated by Chairman Mao in the first article of this series.

Hong proclaimed that a Taiping Heavenly Kingdon had started, and years were since counted from 1851, as the first year of the Taiping era. Taiping, the name under which the movement became nationally and internationally known, means “Great Peace,” and the word connected Hong’s group to a century-old Chinese millenarian tradition.

Hong promised to his followers, now numbering in the tens of thousands, a New Jerusalem, a heavenly city as the center of the Heavenly Kingdom, but probably in 1851 he did not know himself what city it was to be. His army advanced from South to North and from West to East, conquering city after city, in each one acquiring new followers seduced by Hong’s religious message and also finding in it a way to express different grievances against the Qing power.

One after the other, from 1851 to 1853, the Taiping conquered Yongan (in Mengshan county, Guanxi province), Anqing (Anhui province), Wuchang (now part of Wuhan, Hubei province, well-known for the COVID-19), and finally Nanjing, on March 19, 1853.

In the battles, they lost in 1852 two of their leaders, Feng Yunshan and Xiao Chaogui. Since Xiao channeled Jesus, and Yang Xiuqing channeled God the Father, Xiao’s death made Yang the sole purveyor of messages from Heaven besides Hong. In view of subsequent events, some historians suspect that Xiao was killed by a plot engineered by Yang rather than by Qing enemies. But of this conspiracy there is no evidence.

From city to city, the Heavenly Kingdom was taking shape. By 1853, it seemed unstoppable. It will both flourish and collapse in Hong’s New Jerusalem, Nanjing.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.