The Taiping, “the most important movement of the 19th century,” can only be understood in religious terms. It originated from a mystical experience.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 2 of 5. Read article 1.

The Taiping, in the words of theologian Ronald Boer, “was the most important and largest movement anywhere in the world in the nineteenth century. The revolutionary sparks in Europe of 1848 were a side-show by comparison.” Yet, the Communist and nationalist interpretations I mentioned in the previous article, have somewhat obfuscated its understanding. Not knowing what to make of the Taiping, scholars have relegated them to the margins of 19th-century history. Unless they took courses in the history of China, most Western college students may have never heard of them.

As recent scholars such as Carl S. Kilcourse (in his Taiping Theology, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016) have demonstrated, the Taiping can only be understood in their own terms, as a new religious movement. Reducing it to a purely political, either proto-Communist or nationalist, phenomenon may only lead to serial misunderstandings.

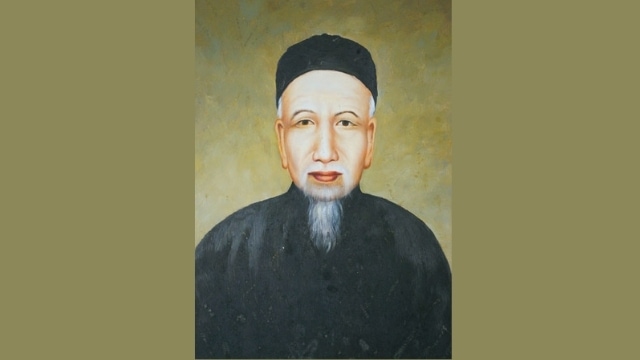

As many other new religious movements, the Taiping started with a founder and his (or her) extraordinary religious experience. Hong Xiuquan (1814–1864), the future Heavenly King of the Taiping, was born as Hong Huoxiu on January 1, 1814, in Fuyuanshui village (now the Fuyuan Reservoir area) in Huaxian county (now Huadu district), Guangdong province, thirty miles north of Guangzhou (at that time called Canton). His parents were farmers from the Hakka minority, a subgroup of the Han Chinese. Besides speaking a different variety of the Chinese language, the Hakka were different from the Cantonese because their women did not bind their feet to make them small, which was regarded as attractive in the Chinese tradition. This detail will be eventually important for Hong. He will find thousands of dedicated followers among the Hakka, who felt somewhat discriminated. Conversely, the Hakka will be ferociously repressed after the failure of the Taiping Rebellion for the support they had given to Hong.

Soon, the Hong family moved to another village of the area called Guanlubu, in present-day Huadu district, Guangdong province. The home where the future religious leader grew up, and indeed the entire village, were destroyed during the repression following the Taiping Rebellion, but the residence has been reconstructed by the CCP as a museum honoring Hong.

Hong Huoxiu was the fourth child in his family, but his father believed him to be the brightest, and destined him to be a scholar, unlike his two brothers and one sister who helped with the family farm (the sister, Hong Xuajiao, 1830?–1856?, will eventually become a general in her brother’s Taiping army). Hong Huoxiu devoted himself to studying the classics, supplementing the meager allowance his parents were able to give him by teaching in the local school.

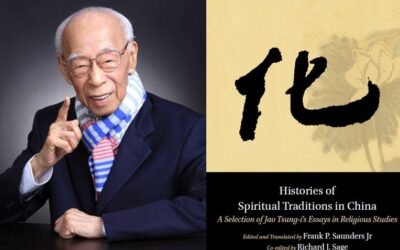

Scholars prepared for examinations at the local and provincial level, which if passed would lead to a career in the imperial bureaucracy. Exams were extremely demanding, and quotas made only a small fraction pass among thousands of candidates. Hong passed the local examination in Huaxian county three times, and went to Canton for the provincial one. In 1836, when he was entering Canton for his second examination, he was given by a traveling Western missionary, probably American Congregationalist minister Edwin Stevens (1802–1837), a set of Christian pamphlets, Good Words to Admonish the Age, written by the Chinese convert Liang Fa (1789–1855). Too busy with his examination, Hong just flipped through the pamphlets. But he kept them, and they will become very influential on him later.

In 1837, Hong learned that he had not passed his provincial examination for the third time. By all testimonies, this did not make him a bad scholar. On the contrary, his knowledge of the Chinese classics was extensive and deep. Only one to two percent of the candidates passed the provincial examination at that time. Yet, he had expected to pass, and had a nervous breakdown. He was delirious for more than one month, and his relatives expected him to die. But he recovered, and reported what would today be called a near-death experience.

He had entered Heaven, and had been greeted by a tall man dressed like a high imperial dignitary, who revealed to Hong that he was his physical father as well as the universal father of all humanity. He also introduced the astonished young Chinese to an extended family, including Hong’s mother, Hong’s own celestial wife, called the First Chief Moon, Hong’s and the First Chief Moon’s celestial son, and Hong’s elder brother, who in turn had a wife and children in Heaven. The father told Hong that he used to be worshipped as the only God in ancient times, but the demons corrupted China and made it fall into polytheism and demon worship. For this reason, Hong, as the younger son of God, with the new sacred name of Hong Xiuquan, will be sent back to earth with the mission of slaying the demons and restoring the old religion.

Hong struggled for several years to understand what the vision meant, and in the meantime decided to try the provincial examination a fourth time. He failed again in 1841, which led him to a period of soul-searching. In 1843, a friend visited his home, noticed Liang Fa’s pamphlets, and asked to borrow them. When he returned the booklets, he told Hong he should read them too. He did, and found there the key to his vision. He understood that the “Father” he had met was the Christian God, the One True God, and that the Father’s elder son was Jesus Christ. That made Hong himself God’s second son, and Jesus’ younger brother.

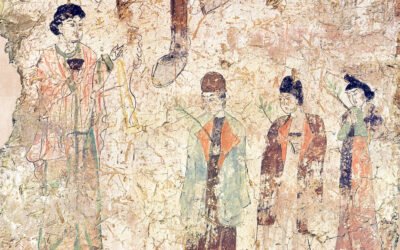

Hong also understood that ancient China had practiced true monotheism, recognizing only one God, Shangdi, who in fact was one and the same with the Christian God. Unfortunately, one after the other, China’s imperial dynasties had been misled by demons and had started worshiping other gods, in fact demons, coming from Taoism or Buddhism. Worse still, the emperors had decided to call themselves divine, a blasphemy against the One True God, and one of which the Manchu emperors of the Qing dynasty who reigned in Hong’s time continued to be guilty of. Hong, as God’s younger son, had been sent to earth to literally destroy the demons, smashing the idols in which they resided in temples throughout China, defeat the Qing dynasty that blasphemously claimed to be divine and continued to spread the worship of the demonic gods, and install a new Heavenly Kingdom with himself as king.

As other religions, what was initially called the religion of the “God-Worshippers” started with a first vision. The first Western missionaries who were told about it found it heretical and blasphemous, as they believed that Hong was claiming to be God. However, they misinterpreted his theology. For Hong, being the “son of God” did not mean to be God, and calling any human being God would violate the monotheistic principle of God’s unicity.

Later missionaries who approached Hong understood that what they saw as his heresy rather consisted in rejecting the divinity of Christ. According to the Taiping, neither the elder son of God, Jesus Christ, nor his younger son, Hong, were part of the deity, although they were exceptional and exalted human beings with a special mission. Hong also maintained that, as elder brother, Jesus had a superior position in the heavenly hierarchy with respect to the younger brother Hong. But both were just creatures.

When in his later years he was criticized by a missionary who accused him of Arianism, Hong answered that, in insisting that Jesus was subordinated to God the Father, and not “of the same substance” with him, Arius (256–336) was right and the Council of Nicaea that condemned him was wrong.

But how did this theology gather tens of thousands of Chinese followers? We will try to answer the question in the next articles of the series.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.