The word “right” has a fascinating history dating back to the Neolithic and the Bronze Age. We can learn from it what went wrong with Tai Ji Men in Taiwan.

by Massimo Introvigne*

*A paper presented at the international webinar “The Tai Ji Men Case: Human Rights vs. Human Wrongs,” co-organized by CESNUR and Human Rights Without Frontiers on December 10, 2024, UN Human Rights Day.

Celebrating Human Rights Day, I would like to start with some comments on one of the most fascinating words in Indo-European languages, “rights.” I believe we can also learn, as it often happens when we deal with words, why our individual and collective “rights” are the cornerstone of society.

In the proto-Indo-European language, supposedly emerging during the late Neolithic period and the Bronze Age, one very important word was “reg.” This was originally a verb: “to straighten” or “to rectify.” It had already a deep meaning, since it could be used in the physical world, as in making a wall straight, and in a metaphorical sense, as in straightening or rectifying something that was wrong. “Rectify” also includes the root “reg” and means “to make something right.” Then, “reg” was used as a noun to indicate something that was straight, perhaps because it had been straightened. This was a desirable quality, both in the physical world and in the metaphorical use, and “reg” acquired the meaning of “right.”

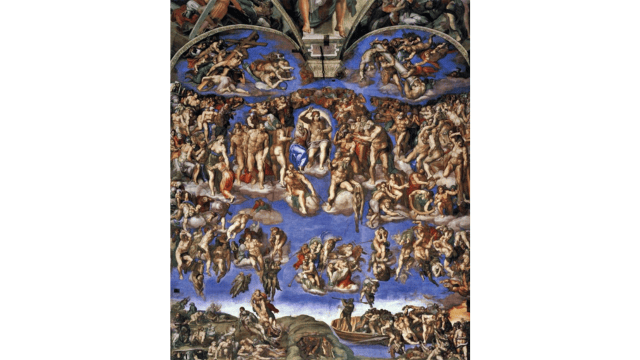

However, the richness of the Indo-European word “reg” does not end here and has fascinated generations of scholars. “Right,” in the sense of straightened, is opposed to “twisted.” In the metaphorical or moral use, “right” is the opposite of “wrong.” But “right” is also a direction, as opposed to “left.” This is already an interesting question: why the language indicates that “right” is a good direction and “left” is not? Note that this idea does not exist only in Indo-European languages. We found it in Hebrew and Aramaic texts of books of the Bible, where God in the Last Judgement sends the saved to the right and the damned to the left. All Christians know the prophecy of the Gospel of Matthew 25:41, when Jesus through the image of a king tells of when God “will say to those on his left, ‘Depart from me, you who are cursed, into the eternal fire prepared for the devil and his angels.’” Those “on his left,” indeed, while those “on his right” will be saved. This is because the “right” is the place of people whose lives were straightened or rectified and the “left,” by opposition, the place of twisted, unrectified lives.

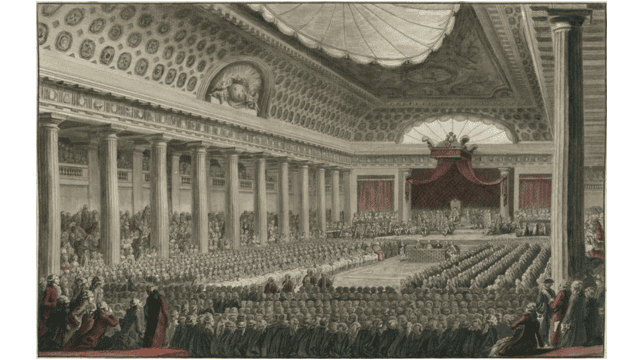

At this stage, we may be tempted to jump to politics, and indeed the pun “the right is right, and the left is wrong” has been used at various times in various versions. However, it is more than a joke. We know that we use in politics the words “right” and “left” because at the time of the French Revolution in the Estates General of 1789 the monarchists and the conservatives were seated on the right and the radicals on the left. But this was not coincidental. The conservatives were mostly cultivated people who knew that “rex,” in Latin “king,” comes from the same root of “right,” with the idea that the king should guarantee the harmony of a righteous and rectified society. So those in favor of the “rex,” the monarchists, should seat at the right and identify themselves as the political “right.”

Finally, “rule” comes from the Latin “regula.” The same root “reg,” again. The “regulae,” the “rules,” offer a map to make our lives and society right. And in a traditional society the “rex,” the king, supervises the application of the “regulae,” the rules, which are in this sense “things of the king.”

As opposed to all this, “rights of Man,” which became “human rights” in the 20th century to underline they also included women (but French still use “droits de l’homme”), is a comparatively recent expression. It was introduced by the Enlightenment in the 18th century to replace the older “natural rights” and consecrated by the French Revolution. Some Enlightenment philosophers did not like the expression “natural rights” as it was used by the Catholic Church, which they opposed. The next generation of secular philosophers also raised doubts on the concept of a universal human nature. Finally, however, the expression “human rights” was generally accepted (including by the Catholic Church) and separated from its ideological origins. “Human rights” are just the rights all human beings have as humans without distinction.

When we speak of “human rights,” however, we should not forget the origin and the very long history of the word “rights.” It indicates that what is twisted should be rectified. A just society is founded on making right what was wrong. This is the aim of justice and, when “human rights” have been violated, of transitional justice.

When Taiwan incorporated the Two United Nations Human Rights Covenants into its domestic law in 2009 it undertook to create a system where past wrongdoings should be rectified or “made right,” and in the future human rights should be affirmed and human wrongs should be punished. This has obviously not happened in the Tai Ji Men case, a noticeable collection of wrongs. The wrong perpetrated against Tai Ji Men since 1996 has not been rectified or made right.

The right has not triumphed over the wrong by punishing those who wronged Tai Ji Men either. On the contrary, the worst perpetrator, Prosecutor Hou Kuan-Jen, has not been punished but repeatedly promoted. The idea of “right” is the cornerstone of a free, harmonious, and just society but this idea is denied every day in Taiwan as long as the Tai Ji Men case is not solved.

I would like to conclude by praising the Tai Ji Men dizi (disciples) who fight for justice by studying in depth legal and tax issues but also by continuing their spiritual struggle to bring peace, love, and conscience to the world. By doing this, they affirm what is also a Christian idea, that rectifying wrongs is ultimately a spiritual achievement that comes from God but also requires the daily efforts of women and men of good will.

Christians still sing the “Golden Sequence,” which dates back to the 13th century, where they call on the Holy Spirit to come and “rege quod est devium,” “straighten what is twisted”—and note the use of “rege,” again. Taiwan should “straighten what is twisted” too. It is a legal fight, but it is also a spiritual fight—where conscience will one day prevail.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.