The most significant Italian new religious movement of the 19th century did not exist only in Tuscany. A book reconstructs his history in the Sabina region.

by Massimo Introvigne

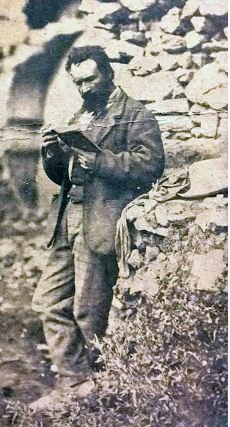

There is a substantial scholarly literature in Italian—and a handful of texts in English—devoted to David Lazzaretti, the charismatic prophet of Mount Amiata in Tuscany who was shot dead by the police in 1878 while leading a peaceful religious procession. The attention is well deserved: Lazzaretti founded the most significant new religious movement in 19th-century Italy, blending millenarian prophecy with a Christian form of communism. He has been interpreted as a “primitive rebel” (Eric Hobsbawm), a proto-socialist lacking Marxist theory, or a mystical visionary whose apocalyptic theology fused Catholic imagery with radical egalitarianism.

Born in Arcidosso in 1834, Lazzaretti began as a carter and lay preacher before experiencing visions that led him to proclaim himself the “Davidic prophet” and at the origins of the Chiesa Giurisdavidica. His movement attracted thousands of peasants disillusioned with both the Church and the liberal state, and his sermons—delivered in poetic Tuscan dialect—called for moral renewal, social justice, and divine intervention. His death at the hands of the Carabinieri turned him into a martyr for many, and his legacy has been studied through the lens of religion, politics, and popular resistance.

Yet “‘L’infame setta dell’empia dottrina’: L’avventura profetica di David Lazzaretti nella Sabina” by Paolo Lorenzetti, published in 2024 (Foligno: Il Formichiere), offers a fresh and compelling perspective. Unlike most studies, which focus on Lazzaretti’s activities in Tuscany, Lorenzetti turns his gaze to the Sabina—a rugged region straddling Lazio and Umbria—where Lazzaretti spent formative time and gathered a lesser-known circle of followers. In towns like Scandriglia, Ponticelli Sabino, and Montorio Romano, he inspired small communities of believers who saw in his message a spiritual lifeline amid crushing poverty and social marginalization.

Lorenzetti reconstructs the history of these now-defunct Sabine branches of the Chiesa Giurisdavidica with archival precision and ethnographic flair. He recounts Lazzaretti’s mystical retreat into a cave near Montorio Romano, where he secluded himself for days while a disciple passed food and water through a narrow crevice—a scene that evokes monastic asceticism and prophetic drama. These Sabine followers, like their Tuscan counterparts, were peasants searching for meaning in a fractured world. Some drifted toward Protestant communities in Poggio Mirteto and Forano, while others joined the messianic movement of Oreste De Amicis, the so-called “Messiah of Abruzzo.”

The book also enriches our understanding of Lazzaretti himself. Lorenzetti uncovers new details about his trial in Rieti and his encounter with John Bosco, the Catholic founder of the Salesian Order, in Turin. While official Catholic biographies later dismissed the meeting as insignificant, Lorenzetti cites a warm letter of support Bosco wrote to Lazzaretti during his legal ordeal—suggesting that the saint may have seen something admirable, or at least sincere, in the prophet’s mission before Church authorities branded him a heretic.

Perhaps most intriguingly, Lorenzetti documents the emergence of an early anti-cult discourse around Lazzaretti’s movement. The book’s title, “L’infame setta” (The Evil Cult), echoes the denunciation by the parish priest of Scandriglia. This language, rooted in Catholic polemics against heresy, began to morph into a secular vocabulary of suspicion. Lorenzetti shows how bourgeois critics and Catholic clergy converged in their opposition to Lazzaretti’s “Christian socialism,” anticipating the modern use of “cult” as a label for religious movements deemed subversive or criminal. Cesare Lombroso, the founder of modern criminology (and himself, paradoxically, a Spiritualist), applied this terminology to Lazzaretti’s followers, inaugurating a new lexicon of repression.

Lorenzetti’s book is a stylish exploration of a neglected chapter in Italy’s religious history. It invites readers to look beyond the familiar Tuscan epic and into the Sabine hills, where prophecy, poverty, and politics once converged in quiet rebellion. For English-speaking audiences intrigued by spiritual heterodoxy, millenarian movements, or the sociology of belief, the book offers a vivid and valuable window into the world of David Lazzaretti—and the lives he touched far from Mount Amiata.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.