Hamas saw the 1993 Oslo Accords and the establishment of the Palestinian National Authority as an Israeli-American plot against the Islamic movement.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 6 of 8. Read article 1, article 2, article 3, article 4, and article 5.

The first Hamas attempted suicide bombing, in April 1993, did not cause any victim. A car bomb driven by a Hamas militant exploded between two Israeli buses, from which, however, the passengers had disembarked.

On September 13, 1993, the PLO and Israel signed the first of two Oslo Accords, which paved the way for self-rule by the Palestinian National Authority in the Territories. Hamas led the “rejection front” to the peace accords, but must take into account the fact that a significant part of the Palestinian population was showing war-weariness and supported the agreements. Hamas leader Yassin was still in jail, from where he issued an appeal urging to avoid a civil war with the PLO. The issue was serious and concerned the very survival of Hamas, confronted simultaneously with the end of the Intifada, a peace agreement supported by the majority of the Palestinian public opinion, and Arafat’s commitment to restrict terrorists’ freedom of movement in the Territories. The Hamas leadership publicly condemned the Oslo Accords, but it had to take into account the new reality and move with renewed caution.

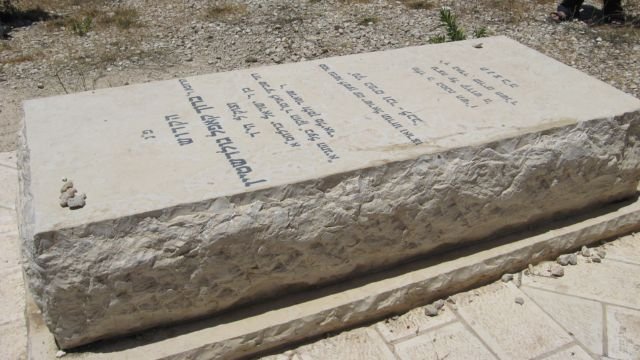

A tragic and unforeseen episode, however, allowed Hamas to argue that terrorism remained a necessity in the face of specific Israeli provocations. On February 25, 1994, an Israeli settler, Baruch Goldstein (1955–1994), opened fire on praying Muslims in Hebron, killing twenty-nine. Hamas responded, beginning in April, with a series of suicide bombings against Israeli regular buses.

On May 4, 1994, with the Cairo Accords, Arafat pledged to prevent organized attacks against Israel from the territory controlled by the newly formed Palestinian National Authority, which took office in June. A few days after the Cairo Accords, the al-Qassam Battalions of Hamas and Fatah’s military wing signed a non-belligerence pact. The pact, however, as well as the Cairo Accord, covered only attacks organized from the Territories. If there were attacks in Israel organized by terrorists operating within Israeli territory, the responsibility for preventing them laid with the Israeli police and services, not with Arafat.

Thus, when on October 19, 1994, Hamas pulled off its most spectacular suicide bombing in Tel Aviv, killing twenty-one Israeli civilians and a Dutch citizen in the explosion of a commercial bus, everyone was quick to declare that it was the initiative of an “autonomous” cell operating exclusively in the Israeli territory. This was not the case, and Hamas and the PLO suspected each other of violating the agreements. Hamas also accused Arafat of transmitting information about fundamentalist leaders to the Israelis. Violent clashes erupted a month later, on November 18, 1994, at the end of the Friday prayers in a Gaza mosque. A confrontation between Islamic militants, many of them linked to Hamas, and Palestinian National Authority police left fifteen dead and about two hundred wounded on the ground.

A detailed study of Hamas terrorist operations before 9/11, which produced several hundred deaths, is beyond the limits of this series. The three-player game between Hamas, the PLO, and Israel continued according to a tragically predictable pattern. To each progress in the Israel-PLO peace talks Hamas responded with attacks, which were followed by an Israeli crackdown, a fragile moratorium agreed upon between the PLO and Hamas in an attempt to loosen the grip of repression, a resumption of PLO-Israel peace talks, and new Hamas attacks that reopened the cycle.

In 1995, Hamas political leader Abu Marzuq—with whom, in fact, the United States had tried in past years to negotiate—was arrested in New York. In May 1997, despite a 1996 decision by a U.S. judge in favor of his extradition to Israel, he was freed and deported to Jordan with the agreement of the Israeli government. Abu Marzuq’s detention came at a critical time for Hamas, which had to decide whether or not to participate in the Palestinian elections set for January 20, 1996. In the fall of 1995, Hamas was in possession of polls that put it at fifteen percent. The conspicuous decline, compared to the 1992 professional and student elections, was attributed to the popularity of Arafat, who had at least gained a semblance of an autonomous Palestinian entity, but also to the Palestinian National Authority’s tight control over all media. From a lively internal debate about whether or not it was convenient to participate in the elections emerged the possibility of a “proxy” participation through a political party, the National Islamic Salvation Front, of which Arafat himself—aware that an election without Hamas will be considered by many as not representative—contentedly announces the founding in November 1995. The Front was not controlled by Hamas, but by the Muslim Brotherhood. All members of its Political Bureau were part of Hamas, but some of the founding members of the Front were not.

The Front’s participation in the elections, however, was made conditional by the Hamas leadership on the outcome of negotiations that took place in Cairo in December 1995 with the Palestinian National Authority. They failed, mainly because of disputes over the voting mechanism and electoral constituencies, which seemed to Hamas to be tailor-made to ensure Fatah’s success anyway. In reality, a complex game for hegemony within Hamas was also being played around the elections between the “external” leadership (in exile in Jordan and Syria), which was less inclined to any form of compromise with Arafat, and the “internal” leadership, grappling with the daily life in the territories controlled by the Palestinian National Authority and tending to be more accommodating.

The “outside” leadership prevailed, and Hamas announced that theological reasons prevented it from participating in the elections. It explained that the elections descended from the Oslo Accords and participation implied recognition of those agreements, including the doctrinally illicit principle of the coexistence of two states, Israel and a Palestinian state, in Palestine. Hamas held firm to the prospect of a single Islamic state from the Mediterranean to the Jordan, and continued to declare that this was due to theological more than to political reasons. Fatah, thus, participated in the elections having as rivals only two small secular parties, one communist and one social-democratic, and, of course, won them overwhelmingly. Two months after the elections, in March 1996 the Palestinian National Authority officially registered the National Islamic Salvation Front among the recognized parties. The formation did not gain any particular political visibility independent of Hamas, but remained a vessel that could be used in future elections.

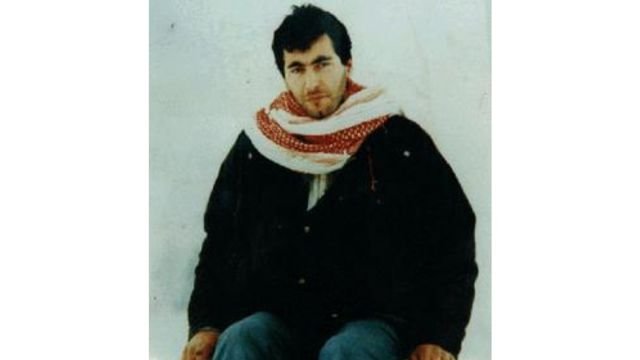

The election debate and negotiations with Arafat resulted in a moratorium in Hamas suicide bombings, which effectively ceased from July and August 1995—marked by two additional bus attacks in Ramat Gan and Jerusalem—until the elections. However, on January 5, 1996, Israeli intelligence, which had already succeeded in assassinating Palestinian Islamic Jihad leader Fathi Shiqaqi in Malta on October 26, 1995, killed Yahya ‘Ayyash (1966–1996) in Gaza. This leader, the brain behind the suicide strategy within the al-Qassam Battalions, had been ironically called the “engineer” in one of his speeches by Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin (1922–1995), a nickname later adopted enthusiastically within the fundamentalist movement.

The climate was already red-hot in the aftermath of the assassination of Rabin himself, who was killed by an Israeli extremist on November 4, 1995. Hamas announced revenge. On February 25 and March 3, 1996, two suicide bombings perpetrated against buses on the same Route 18, in Jerusalem, killed forty-five passengers. This was the most dramatic terrorist act against Israel up to that time. There ensued, according to the usual pattern, a campaign of repression led by both the Israelis and the Palestinian National Authority, followed by negotiations between Hamas and Arafat for a new moratorium on terrorist attacks.

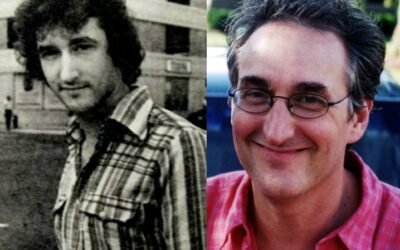

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.