Understanding where Hamas comes from is essential to read recent events correctly. A new “Bitter Winter” series.

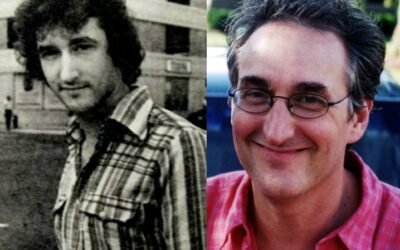

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 1 of 8.

While several valuable studies are devoted to the recent policies of Hamas, this series aims to reconstruct its origins, and the period from its foundation to the terrorist attacks of 9/11 2001. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, I visited Israel and the West Bank repeatedly and interviewed both Israeli and Palestinians scholars, police and intelligence officers, and militants. This was at the origin of a book on Hamas I published in Italian and Czech in 2003, and sections of subsequent books I published on Islamic “fundamentalism,” a contested category in itself.

Hamas constitutes the largest Muslim Sunni “fundamentalist” movement in the Middle East today. Understanding it therefore requires an analysis of Islamic “fundamentalism” in general.

The category of “fundamentalism” originated with reference to the Protestant Christian world and only by analogy was later extended to other religious traditions. Some common definitions of “fundamentalism” in general—for example, “Fundamentalism believes that a sacred scripture is infallible and needs no interpretation”; or “Fundamentalism believes that a clear distinction between the political and religious spheres is difficult”—are of little use in identifying a specific subcategory within Islam, because they would rather apply to Islam in general. If we adopt these definitions, we must conclude that most Muslims are fundamentalists (with the exception of a minority of liberals). Instead, we can give a fairly precise definition of Islamic fundamentalism, if we refer to a specific movement that arose between World War I and World War II, in 1928 in Egypt, the date of the founding of the Muslim Brotherhood by Hassan al-Banna (1906–1949), and in 1941 in the Indian subcontinent, where Maulana Sayyid Abul Al’a Maududi (1903–1979) founded the Jama’at-i Islami.

In turn, twentieth-century fundamentalism has its roots in the “Salafist” (from salaf, the “pious ancestors” to whom Muslims must return) movement of the 19th century, which aimed to raise Islam from the state of decadence into which it had fallen. In fact, from this Salafist revival led by figures such as Djamal el-Din Afghani (1839–1897) and Muhammad Abduh (1849–1905), different strands fed into the 20th century. Some of them read the 19th-century Salafiyya through its late exponent Rashid Rida (1865–1935). He was a key figure who represented, according to French scholar François Burgat, “the transition from the Salafiyya to the conceptions of the Muslim Brotherhood.”

The Islamic fundamentalist movement (I will skip the brackets from now on, but remain aware that the category is controversial), at least in its more radical ideologists, set three ambitious goals in sequence. First, the enforcement of Islamic law (shari’a) in every Islamic community. Second, the unification of Islamic-majority countries into a single politico-religious reality led again by a caliph. Third, the resumption by the restored caliphate of the original dream of spreading Islam outside its present boundaries. Outside observers often add a fourth characteristic: fundamentalism is a movement with a populist character. It distrusts the powers that be in Islamic countries, seen as guilty of not fully enforcing the shari’a. It theorizes the possibility of overthrowing them by force, often in an apocalyptic and millenarian key. It has no sympathy for the ulama and other professionals of the sacred either, whom it considers as subservient to political authorities. The latter are also held responsible for the social injustices prevalent in Muslim-majority countries and contrary to the egalitarian character of the Qur’an.

Obviously, not all Muslims are fundamentalists. In the Islamic world, to reduce to a simple scheme a much more complicated situation, four currents are different from fundamentalism and sometimes its opponents. The nationalists advocate within the Islamic world nation-states, which are distant from the dream of the caliphate. The conservatives and the traditionalists often agree with the fundamentalists on shari’a but can be distinguished from them by the profound respect they pay to constituted authorities, based on the principle that many lesser evils are tolerable in order to avoid the greater evil which is civil war among Muslims. The modernists advocate the adoption of Western models and only in some countries have a real following; elsewhere, their main supporters are Western media. Some of the political expressions of the complex world of Sufism are also hostile to fundamentalism. Some, not all, because there was historically no shortage of Sufis who were fundamentalists and fundamentalists who were Sufis, such as the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood himself, Hassan al-Banna (1906–1949).

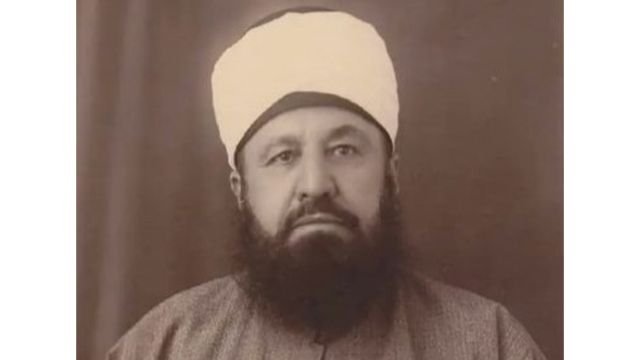

Hamas literature claims as its precursor Shaykh ‘Izz-Id-Din al-Qassam (1882–1935), for whom the movement’s military branch was named. Al-Qassam was born in Jebla (now Jableh), in Syria’s Latakia district, in 1882. His father was the murshid of the Sufi Qadiriyya brotherhood in Jebla. According to some biographers, he was also initiated into the Naqshbandiyya, a brotherhood that will later play a prominent role in anti-colonial resistance in Syria. Al-Qassam was trained in the school attached to the mosque whose imam his father was. He then went to Cairo to study at the prestigious al-Azhar University. There he met Rashid Rida, whose ideas on the restoration of shari’a are important for the whole fundamentalist movement.

Returning to Jebla in 1909, al-Qassam devoted himself to teaching in a school run by the Qadiriyya. The ensuing revival demonstrated the full compatibility of a certain interpretation of Sufism with the call to jihad. Indeed, the revival around al-Qassam, while retaining distinct Sufi characteristics, immediately presented itself as militant and military. Al-Qassam sought a cause around which the need to defend the threatened Islamic community in arms could manifest itself. He believed he had found it in the Italian invasion of Libya in 1911. He called the faithful to jihad and gathered a battalion estimated at between 60 and 250 mujahidin. They went only as far as Alexandretta, where the Ottoman government forced them to return to Jebla.

The appointment with jihad was, however, only postponed. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire after World War I prompted al-Qassam’s militia to armed struggle in an anti-colonial vein, first against the Syrians of the Alawite faith, believed to be allies of the French occupier, then directly against the French. Sentenced to death in absentia by a French military tribunal, in 1921 and having abandoned all hope of success in the anti-colonial struggle, al-Qassam left for exile in Haifa, Palestine.

The Haifa period was decisive for the elaboration of al-Qassam’s ideas. There, he joined the Jamiat Islamiyya (“Islamic Association”), where he collaborated with another Syrian anti-colonialist exile and disciple of Rashid Rida, Kamal al-Qassab (1853–1954). The two Syrians became notorious for a polemical campaign against a number of funeral practices considered superstitious and un-Islamic. They were accused of being “Wahabis,” i.e., followers of the traditionalist movement founded in Saudi Arabia in the 18th century by Muhammad Ibn Abdul Wahab (1703–1792) and closely linked to the Saudi ruling house. They retorted that they were not Wahabis, since Saudi-style Wahabis are opposed to Sufism in general, while they only wanted to fight against its degenerations. In fact, in those very years al-Qassam was initiated into the Sufi Tijaniyya brotherhood, which will remain a decisive influence on his spirituality until his death.

The Muslim Brotherhood organization was founded, as mentioned earlier, in 1928. That al-Qassam formally belonged to it is rather unlikely. However, a similarity of ideals can be found in the common reference to Rashid Rida, from whose heirs the founder of the Muslim Brothers, al-Banna, had acquired the ownership of the periodical “al-Manar,” to which Rida’s fame was inseparably connected. In addition, al-Qassam became the president of the Haifa branch of an organization considered close to the Muslim Brotherhood, the Young Men’s Muslim Association (YMMA; the name recalled the Young Men’s Christian Association, YMCA, founded in London in 1844).

Al-Qassam’s ideas about how an Islamic state should look like in the late 1920s were not particularly elaborate, He certainly envisioned for Palestine, freed from foreign influences, a “Qur’anic” society in which Muslims loyal to the shari’a could coexist with Christians who would accept the subordinate status of “dhimmi” and cooperate loyally with the Islamic majority. At the same time, al-Qassam strongly opposed any form of Jewish settlement in Palestine.

Gradually, the struggle against Jewish settlers and the British power accused of protecting them became the new priority that al-Qassam presented as the duty of the entire Islamic world. Starting in 1930, he organized a secret military group, which, however, encountered recruitment difficulties in the predominantly bourgeois circles of the YMMA. On November 2, 1935, al-Qassam participated in a public political demonstration, but soon thereafter, presaging imminent arrest, went into hiding. On November 21, 1935, he was killed in a skirmish with British police near Jenin.

Beyond the mythological character that the figure of al-Qassam has taken on in Palestine, its importance lies in the dissemination of Rashid Rida’s thought in Palestinian circles, where it paved the way for the later presence of the Muslim Brotherhood and Hamas. Al-Qassam also gave Palestinian fundamentalism a certain pragmatic character, where the urgency of the struggle against Jewish settlers and the British prevailed over grand theorizing, He also argued that clothing, male and female, was less important than participation in the jihad.

Finally, like his contemporary al-Banna, al-Qassam was both a fundamentalist and a Sufi, who reinterpreted Sufism critically by considering an “original” (perhaps mythical) Sufism compatible with the fundamentalist ideal, and presenting Sufi “deviations” as recent and surmountable. Indeed, it should not be forgotten that the Muslim Brotherhood originated in Egypt, a country that has been called “the home of Sufi brotherhoods,” which have millions of members there.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.