A fascinating book shows how Surrealism, “from Mao to now,” served as a survival strategy for dissident artists—and sometimes a gateway to spirituality.

by Massimo Introvigne

Lauren Walden’s “Surrealism and the People’s Republic of China: From Mao to Now” (New York: Routledge, 2026) is the kind of book anyone interested in Chinese society might easily overlook, which would be a mistake. It is not just another art history book. It serves as a reminder that long before “cultural policy” became a term for ideological oppression, Chinese artists had already found a visual language that could navigate around official culture. Surrealism provided a subtle escape: a way to breathe, think differently, and, most surprisingly, seek spirituality in a system that claimed to have eliminated it.

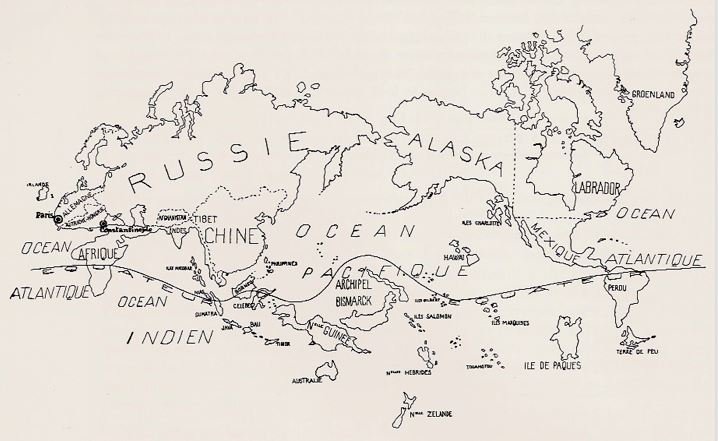

Walden’s narrative begins with an unexpected twist. Surrealism, usually seen as a curious French export, was actually engaging philosophically with China from the beginning. André Breton’s and other European Surrealists’ interest in Daoist concepts—especially “wuwei,” the practice of effortless action—was not a fleeting fancy. Walden demonstrates how Chinese literati painting, which defied the principles of realism, had practiced a form of proto‑Surrealism for centuries. When the Surrealists created their well-known 1929 “Map of the World,” reducing Europe and enlarging China, they were not just being playful. They were recognizing a shared connection.

The book then transitions into the turbulent twentieth century, a time when China’s political chaos made Surrealism oddly relevant. In Republican-era Shanghai, with its colonial enclaves and lively nightlife, Surrealism offered young artists a safe space for creative exploration. Walden highlights figures like Zhao Shou and Sha Qi, who returned from Europe (and Japan) with ideas about Surrealism and combined them with revolutionary rhetoric. Zhao founded the Chinese Independent Art Association in Tokyo in 1934, the first Chinese artistic movement to openly identify with Surrealism, believing it to be “a combination of Eastern spirit and Western techniques.” Sha Qi did not directly acknowledge his Surrealist connections, but Walden believes he acquired a “Surrealist practice” during his years in Belgium.

Next comes the Maoist era, when Surrealism, logically, should have disappeared. Instead, it went underground and transformed into a means of coping with trauma and absurdity. Walden recounts how European visitors like Michel Leiris and Marcel Mariëns struggled to reconcile their admiration for China’s revolutionary spirit with the unsettling silence of its artistic life. Meanwhile, Chinese artists reinvented calligraphy as a Surrealist act: characters blurred into unreadable forms, then reappeared as pseudo‑scripts evoking ancient spirits. Even during the Cultural Revolution, a time hostile to both independent art and mysticism, Surrealism transmitted a quiet resistance. Zhao Shou and Sha Qi tried to survive, with Sha struggling both with mental illness and his fascination with Christianity at a time when religion was proscribed.

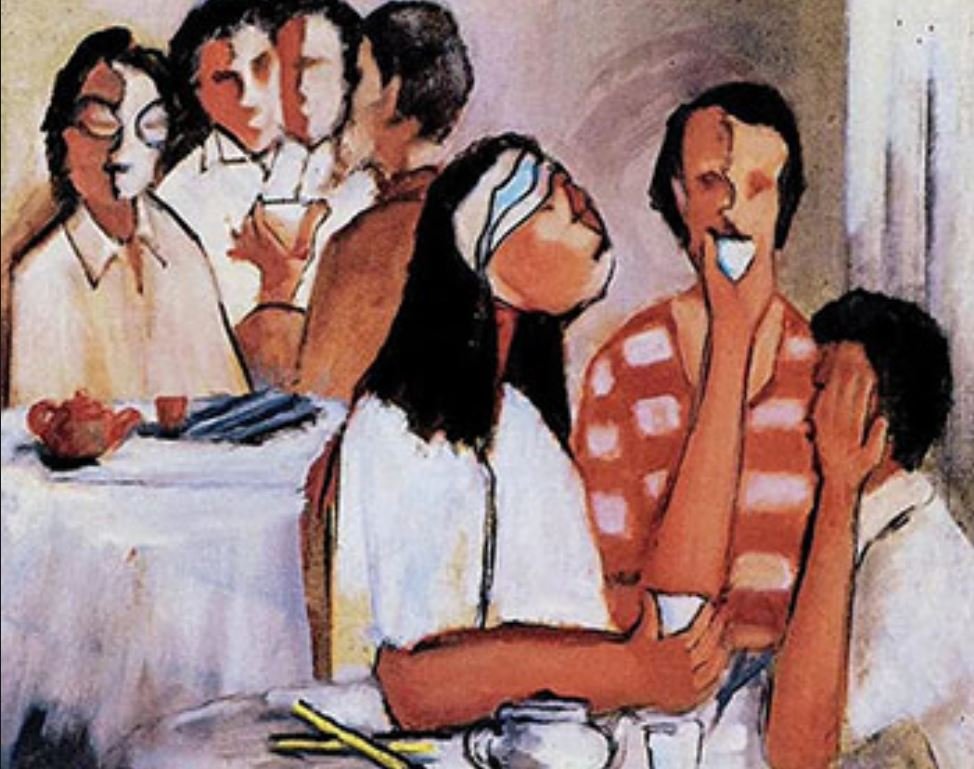

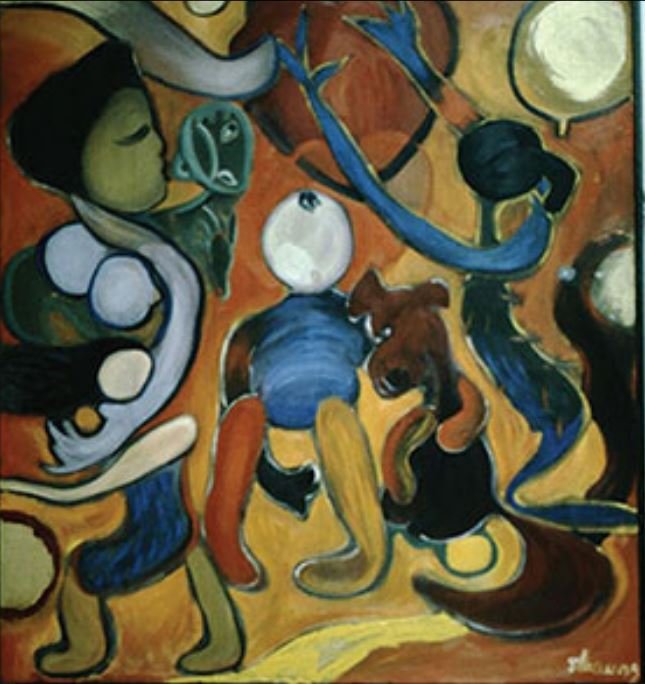

The 1980s saw a surge of repressed desires. As China opened up, artists embraced Surrealism to process the buried issues of previous decades: sexuality, spirituality, memory, and the basic human need to dream. Walden describes art collectives such as the explicitly Surrealist Red Travels group in Jiangsu and the Northern Art Group in Harbin, and painters such as Li Shuang, the first female artist to engage with Surrealism in Deng Xiaoping’s years, who merged references to religion, socialist kitsch, and gendered symbolism into a potent mix of liberation. Surrealism, once a whisper, became a loud expression.

In the current era, Surrealism has become mainstream. Today’s Chinese artists blend Daoist immortals with cartoon characters, Buddhist deities with neon lights, and mystical landscapes with consumer culture. Walden refers to this as “Surrealist Pop,” but it is more than just a style mash‑up. It continues the spiritual negotiation that has been happening for a century: how to stay human, creative, and spiritually alive in a society that swings between materialism and strict ideology.

The final chapter pulls everything together. Walden argues that Chinese Surrealism is not a simple imitation but a unique blend rooted in local traditions. It shows that Surrealism has always been cosmopolitan, open to both metaphysics and Marxism, and eager to blur boundaries—be they geographical, political, or psychological. When Chinese artists adopted Surrealism, they expanded it, adding new spiritual richness and political relevance.

What makes this book so engaging is its argument that Surrealism in China served as a survival strategy. A spiritual practice. A quiet form of defiance. A way of asserting that even when the state tries to control imagination, the subconscious will find a way to escape.

Readers interested in China, the connections between modern art and spirituality, or the unique ways art serves as a refuge will find Walden’s book enlightening. Those who think Surrealism is solely about melting clocks and lobster telephones will learn that, in China, it became something much more vital: a language for the soul.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.