The Aum case proved that the “anti-cult measures” based on deprogramming methods did not work, and ended up adding fuel to the fire.

by Toshihiro Ota*

*A lecture given at the symposium organized by the Institut français de recherche sur l’Asie de l’Est (IFRAE), Paris, March 20, 2025, “L’héritage de l’affaire Aum à la société japonaise: 30 ans après les attentats au gaz sarin du métro de Tokyo.”

Article 5 of 5. Read article 1, article 2, article 3, and article 4.

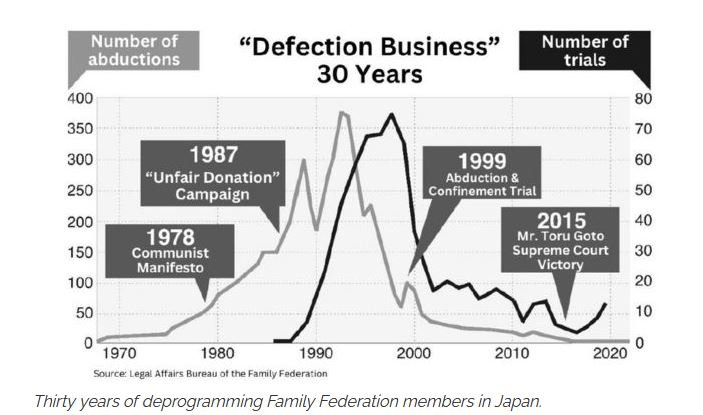

Perhaps due to the shock of the Aum incident, deprogramming became unstoppable, and in 1995, the longest case of deprogramming began. This is the case of Toru Goto, a member of the Unification Church, who was imprisoned for 12 years and 5 months from 1995 to 2008. During his captivity, Goto was not given adequate food and was released in a state of starvation. This case was not prosecuted as a criminal case, but was contested as a civil case, and 22 million yen in damages were determined in 2015.

According to a report by the Unification Church, which has been the main target of deprogramming, the number of abductions and captivity cases has changed, as shown in the figure below. It started in 1966 and peaked in the late 1980s and early 1990s. In the 2000s, reports by some journalists and the spread of the Internet made the reality of deprogramming known to society, leading to a sharp decline. In total, it is estimated that there have been over 4,300 such cases.

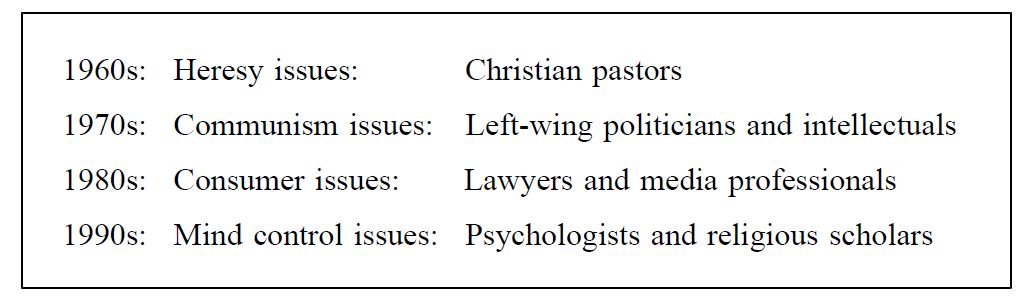

The deprogramming movement in Japan truly deserves to be called “dark history.” The media has rarely reported on it, and there are many unclear points. I want to reexamine it, but at present, I believe that the deprogramming movement expanded its influence by changing its themes from one era to the next. I call this force the “deprogramming network.”

When deprogramming began in 1966, it was carried out by Christian pastors who attacked the Unification Church as a dangerous heresy that had come from Korea. In the 1970s, the struggle over communism began, and left-wing politicians and intellectuals joined the anti-Unification Church movement. In the 1980s, “spiritual sales” became a theme, and lawyers and the media got involved. Then, in the 1990s, the Aum incident led to the spread of “mind control” theories, and psychologists and religious scholars also began to support and accept the deprogramming movement.

The undercover spread of deprogramming movements and networks in Japan naturally impacted the Aum incident. Here are two of the most prominent cases.

The first case is the murder of Attorney Sakamoto and his family. Attorney Sakamoto established the “Aum Shinrikyo Victims Defense Group” in June 1989 and was at the forefront of the opposition to Aum. Negotiations between Attorney Sakamoto and Aum quickly became strained, and in November of the same year, Aum murdered not only Attorney Sakamoto, but also his wife, Satoko, and son, Tatsuhiko. It was a harrowing incident that makes my heart ache whenever I look at it.

What is not widely known is that Sakamoto was a member of the “National Network of Lawyers Against Spiritual Sales” and worked also on the Unification Church issue. Inevitably, Sakamoto’s countermeasures against Aum were based on the method of deprogramming. The idea was that, since “cult” members have lost their free will due to “brainwashing” and “mind control,” they cannot be granted “freedom of religion,” and they must be forced to leave the “cult.” The deprogramming framework is thought to have played a role in the rapid deterioration of negotiations between Sakamoto and Aum.

Furthermore, Attorney Sakamoto belonged to the “Japan Lawyers Association for Freedom” (JLAF), a lawyers’ group affiliated with the Communist Party. As a result, he was in conflict with the government, defending left-wing labor unions and criticizing the public security police for wiretapping the Communist Party. When Sakamoto’s family went missing, members of the JLAF asked the police to investigate Aum, but the police were reluctant to act, and the case went cold. The background to this was that many of the people at the forefront of “anti-cult” efforts were actually communists and leftists.

The second case is that of Aum follower Masami Tsuchiya, who played a key role in the development of sarin. Tsuchiya was originally a doctoral student in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Tsukuba, but he became obsessed with Aum’s faith, and his lifestyle became noticeably disordered. Worried about this, his parents asked an organization called “Busshoin” to help him leave the group. In 1991, Tsuchiya was confined to the organization’s facility for more than a month and subjected to deprogramming.

Busshoin was a facility established by a Nichiren Buddhist priest, offering rehabilitation services for individuals who have emotional disorders or a history of domestic violence. However, these rehabilitations were often accompanied by coercion, confinement, and threats. Tsuchiya himself was reportedly threatened with the words, “If you don’t renounce Aum, we will kill you,” during his confinement.

Tsuchiya’s pride was hurt by being treated as a person lacking judgment, and he began to feel great anger toward his parents and Japanese society. He escaped from captivity and fled to Aum’s dojo, where he became a monk. He was recognized within Aum as a talented chemist. He became involved in the production of sarin to destroy Japanese society and of LSD to induce believers to experience mystical states of consciousness.

From my perspective, the Aum incident was a case in which the “anti-cult measures” based on deprogramming methods did not work well and ended up adding fuel to the fire. However, it is unfortunate that Japanese society did not understand this.

This can be attributed to the complex structure surrounding the fantasy of mind control. First, it has become clear that Aum repeatedly conducted experiments attempting “brainwashing” and “mind control.” On the other hand, anti-cult groups attacking Aum had been developing theories and practices for “deprogramming” to rescue followers from “brainwashing” and “mind control.” Seeing the confrontation between the two, Japanese society came to believe that “cults truly possess mind control techniques,” and that was why Aum had committed such a terrible terrorist attack.

In this way, after the Aum incident, the fantasy of mind control spread even more powerfully and widely in Japanese society. The Unification Church also became the target of conspiracy theories claiming that it used “mind control” to recruit followers and manipulate politicians. The details are unclear at this point, but I think these conspiracy theories may have played a role in the assassination of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe in 2022.

Through my research to date, I have come to realize that what is truly frightening is not “mind control” itself, but the “mind control fantasy.” When people become obsessed with such fantasies, they try to manipulate others to get what they want and end up resorting to unreasonable violence. I hope the Japanese people become aware of the dangers of pseudoscience, such as “brainwashing” and “mind control,” as soon as possible.

Toshihiro Ota was born in 1974. He specializes in religious studies and intellectual history. He received his PhD from the University of Tokyo for his research on Gnosticism and published “The Thought of Gnosticism: The Fiction of the ‘Father’” (Shunjusya, 2009). He subsequently researched Aum Shinrikyo, publishing “The Spiritual History of Aum Shinrikyo: Romanticism, Totalitarianism, and Fundamentalism” (Shunjusya, 2011) and “The Roots of the Modern Occultism: The Light and Darkness of Spiritual Evolution Theory” (Chikuma Shobo, 2013). He currently teaches liberal arts as a part-time lecturer at Saitama University. He has also published a volume collecting lectures on the history of Western religious thought, “The Brief History of Monotheism” (Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2023).