Deprogramming continued in Japan after it was banned in the West. Lawyers and left-wing activists supported it.

by Toshihiro Ota*

*A lecture given at the symposium organized by the Institut français de recherche sur l’Asie de l’Est (IFRAE), Paris, March 20, 2025, “L’héritage de l’affaire Aum à la société japonaise: 30 ans après les attentats au gaz sarin du métro de Tokyo.”

Article 4 of 5. Read article 1, article 2, and article 3.

It was not only Aum that was obsessed with the mind control fantasy. In the “anti-cult” movement that arose after the war, concepts such as “brainwashing” and “mind control” were widely used, and from these concepts a technique called “deprogramming” was further developed.

Ted Patrick, a prominent anti-cult activist in the United States, first proposed the concept of deprogramming.

After World War II, various new religious movements flourished, and many of these groups caused friction with society.

In response to this situation, Ted Patrick argued in the early 1970s that people who had joined “cults” had their free will taken away through “brainwashing,” so they needed to be forcibly removed from the group and unlearn what was deeply programmed in their brains. Because of these theories and practices, he is called “the father of deprogramming.”

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s in the United States, it was common for parents worried about their children joining cults to hire “deprogrammers” to force them to renounce their faith. However, deprogramming often involved kidnapping and imprisoning believers and subjecting them to violence, which gradually became a social problem in the United States. The number of cases in which deprogrammers were convicted of violence also increased.

Activists and deprogrammers, including Ted Patrick, formed the “Cult Awareness Network” (CAN) in 1978. However, this organization was also subject to numerous lawsuits and was ordered to pay $1 million in damages in 1995. As a result, CAN went bankrupt and dissolved in its original form in 1996.

You probably know more about the situation in France than I do so that I won’t go into it here. Suffice it to say that I have heard that deprogramming was carried out sporadically in France during the 1970s and 1980s, but it was immediately criticized as illegal and eventually ended.

In the United States and other Western societies, the pseudoscientific nature of theories about “brainwashing” and “mind control,” as well as the dangers of deprogramming, gradually became known, and a common understanding was formed that these theories and practices were inappropriate as “countermeasures against cults.” However, in Japan, a very different situation has developed. That is to say, from the 1960s to the present, the deprogramming movement has spread strangely.

It is said that the first person to perform deprogramming in Japan was Satoshi Moriyama, a pastor at the Evangelical Church of Christ in Japan. This church is a devout evangelical organization that descends from the Holiness movement. Before the war, the state oppressed Holiness Christians, and Moriyama also had a history of bravely resisting it. And after the war, he turned his efforts toward confronting the proliferation of “heretical” new religious movements, taking a strong stance against them.

Among the religious groups Moriyama saw as particularly dangerous was the Unification Church (now known as the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification), which entered Japan in the late 1950s. Moriyama authored a book criticizing the Unification Church and started a movement to get young people who had joined the church to leave. This gradually escalated, and in 1966, with the help of family members, believers were confined in the church and forced to renounce their religion. In his book published in 1985, Moriyama claimed to have “rescued” more than 130 Unification Church believers.

In 1967, the “Asahi Shimbun” carried an article entitled “The Principle Movement That Makes Parents Cry.” The article claimed that students had been “brainwashed,” prompting them to join the “Principle Movement” (i.e., the Unification Church), run away from home, and abandon their studies. This increased parents’ anxiety, so in September of the same year, the “National Association of Parents of Victims of the Principle Movement” was formed. Consultations with Moriyama and other pastors also increased, and the network of pastors engaged in forced conversions began to expand.

In the 1970s, issues surrounding the Unification Church developed into a political issue in conflict with communism. This was because Sun Myung Moon organized the “International Federation for Victory over Communism” (IFVOC) in South Korea in 1968, and from the 1970s onwards, he also launched an active anti-communist movement in Japan.

In 1978, a left-wing governor was defeated in the Kyoto election due to the efforts of the IFVOC. Threatened by this, the Japanese Communist Party declared a “holy war” against the IFVOC and called for popular and ideological unity. In response, the “National Association of Parents of Victims of the Principle Movement” was formed, and a wide range of left-wing forces, including professors, journalists, lawyers, pastors, and members of parliament, joined forces to oppose the Unification Church.

In the late 1970s, forced deconversion from the Unification Church became widespread, with many members being confined to psychiatric hospitals under the guise of treatment. This trend continued until 1986, when Unification Church members won a civil lawsuit, and later until the Toru Goto Supreme Court decision of 2015.

In the 1980s, Japan experienced a period of great prosperity known as the “bubble economy.” During this time, the Unification Church seemed to have a strategy of promoting worldwide missionary work while using Japan as a source of funds. For this purpose, members of the Unification Church widely sold items such as “spiritual” vases and name seals (hanko) as tools for bringing good fortune.

In response, the anti-Unification Church forces launched a campaign targeting what they called “spiritual sales,” and many media outlets, including television, newspapers, and magazines, joined the movement. In 1987, about 300 lawyers formed the “National Network of Lawyers Against Spiritual Sales.”

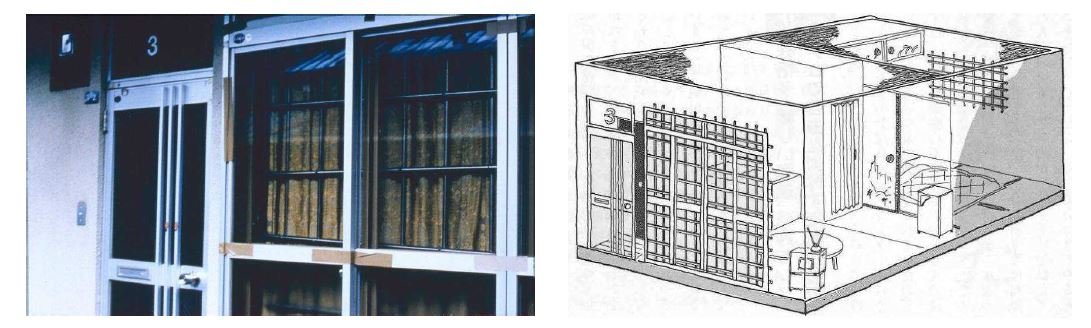

As the issue of the Unification Church became more widely known, the deprogramming movement peaked during this period. Apartments and houses were remodeled into detention facilities one after another throughout Japan. The photo below shows an apartment called “Homei Jutaku” in Hokkaido, where all six units were transformed into confinement rooms fitted with iron bars. A method was also established in which, after being forced to renounce their faith through deprogramming, those deprogrammed would file lawsuits against the Unification Church as “victims of brainwashing.”

Around 1990, the anti-cult movement in Japan faced the issue of Aum Shinrikyo in addition to the Unification Church. However, Aum was a far more violent group than the Unification Church. In 1989, they killed Attorney Tsutsumi Sakamoto and his family, who led the opposition movement against Aum. As we will discuss later, strangely enough, this case remained unsolved, and Aum continued to run wild thereafter. Eventually, in 1995, they carried out the Tokyo subway sarin attack.

Due to the influence of the Aum incident, Japanese society began to voice loud fears about “brainwashing” and “mind control” by cults. In 1993, Steven Hassan’s “Combating Cult Mind Control” had already been translated into Japanese, and in 1995, social psychologist Kimiaki Nishida’s “What is Mind Control” was published. In this way, psychologists, psychiatrists, and religious scholars also began to join the anti-cult movement, and the theorization of mind control progressed. In 1995, the “Japan Society for Cult Prevention and Recovery” (JSCPR) was established as the central organization in this movement.

Toshihiro Ota was born in 1974. He specializes in religious studies and intellectual history. He received his PhD from the University of Tokyo for his research on Gnosticism and published “The Thought of Gnosticism: The Fiction of the ‘Father’” (Shunjusya, 2009). He subsequently researched Aum Shinrikyo, publishing “The Spiritual History of Aum Shinrikyo: Romanticism, Totalitarianism, and Fundamentalism” (Shunjusya, 2011) and “The Roots of the Modern Occultism: The Light and Darkness of Spiritual Evolution Theory” (Chikuma Shobo, 2013). He currently teaches liberal arts as a part-time lecturer at Saitama University. He has also published a volume collecting lectures on the history of Western religious thought, “The Brief History of Monotheism” (Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2023).