Following an economic dispute with the School, the woman who debunked the accusations in the 2000 case now claims they were true. Can we believe her?

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 3 of 3. Read article 1 and article 2.

In the final installment of this series, we confront a troubling reality: the past is no longer safe. The 2000 acquittal of the Buenos Aires Yoga School (BAYS), once considered a settled matter of law and fact, is now being re-litigated—not in court alone, but in the court of public opinion. Part of this revisionist wave is a familiar figure: V.L., whose testimony once helped dismantle the accusations against the BAYS, and who now, after more than two decades, has reversed her story.

This reversal is not merely personal. It is symptomatic of a broader trend—one in which spiritual minorities are targeted through expansive interpretations of trafficking laws, and where ideological actors seek to criminalize difference under the guise of protection. The ghosts of the past have returned, not to haunt the guilty, but to unsettle the innocent.

As explored in the previous article, V.L. was a key witness in the 2000 case. Her testimony, supported by psychological evaluations and forensic reports, painted a picture of a young woman escaping a violent home, not a victim of spiritual exploitation. She denied any sexual or economic abuse within the BAYS, and experts asserted that her mental health had markedly improved after joining the School. Her story was consistent, corroborated, and compelling.

In 2025, that narrative has changed. Following a financial dispute with the BAYS over an alleged labor debt, V.L. joined the new case against the organization. She now claims she was sexually and economically abused, and that the declarations of anti-cult activist Pablo Salum, which she previously dismissed as fantasy, were accurate all along.

This reversal raises serious questions. For 25 years, V.L. denied being a victim and defended the School. Her new testimony contradicts her own past statements and the findings of multiple psychologists and a judge who examined her case in depth. While her current condition—marked by struggles with alcoholism—deserves empathy, it also necessitates caution. The stakes are too high to accept such a dramatic shift without scrutiny.

V.L.’s revisionist story is supported in the media by María Lourdes Molina, a figure whose involvement in the original case was anything but neutral. As mentioned in our previous article, Molina, affiliated with the anti-cult group SPES, participated in a failed “familial intervention” (in fact, a deprogramming) in the 1990s aimed at removing V.L. from the BAYS.

In a recent interview, Molina claimed she does not believe in deprogramming. Yet her actions in the 1990s—documented in court records—suggest otherwise. Deprogramming, a practice that involves forcibly removing individuals from spiritual groups and subjecting them to ideological “de-conversion,” has been widely condemned as unethical and coercive. Courts in the United States and the European Union have declared it a criminal practice.

Molina’s involvement in propagating V.L.’s revisionist story suggests not a neutral reassessment but a continuation of an ideological campaign—one that failed in 2000 and is now being repackaged under the language of trafficking.

V.L.’s half-brother, M.P.S., also talks to the media, supporting the revisionist version and denying that the relationship between the woman and her stepfather was abusive and toxic. As we have seen in our previous article, his testimony in the case decided in 2000 differed. At that time, M.P.S. was already hostile to the School and had no reason to offer arguments supporting its defense.

The current case against the BAYS is built on a familiar anti-cult foundation: accusations of sexual exploitation, psychological manipulation, and trafficking.

The 2000 ruling by Judge Corvalán de la Colina examined these very claims. He found no evidence of coercive persuasion, no signs of psychological servitude, and no credible testimony of sexual abuse. To reopen what is substantially the same case after more than twenty years is not justice; it is legal recursion.

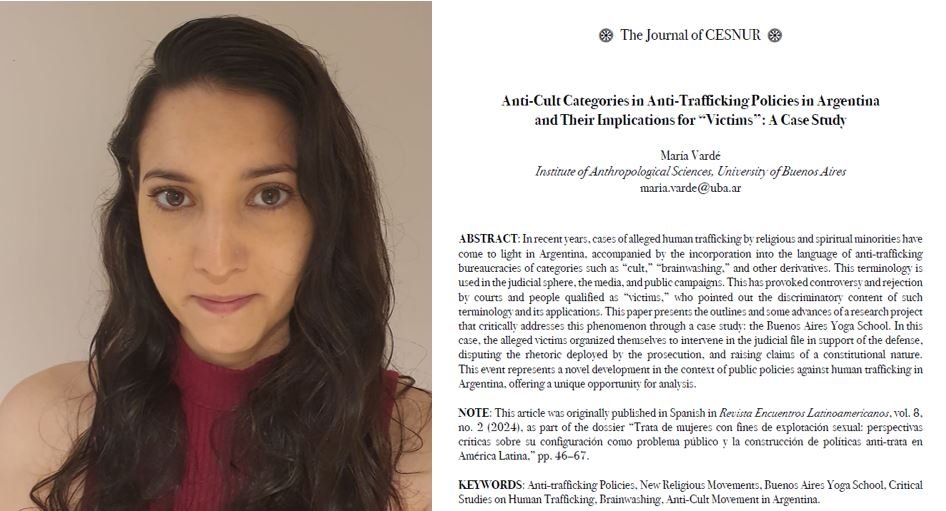

What has changed is not the facts but the framing. The concept of “trafficking” has been expanded in Argentina (and elsewhere) to include a wide range of behaviors—some dangerously vague. As María Vardé argues in a recent article for “The Journal of CESNUR,” this expansion risks criminalizing spiritual affiliation and economic participation within minority religious movements.

This trend is particularly troubling in the case of the BAYS. The School has long been a target of ideological actors who conflate unconventional beliefs with criminal intent. The new case, relying on recycled testimonies and discredited theories, threatens to undo decades of legal clarity.

The role of the media in this revisionist wave cannot be ignored. An article that recounts V.L.’s “return home” does so with a tone of triumphalism, as if her reversal validates the original accusations. It fails to mention the extensive psychological evaluations that once confirmed her mental competence, or the forensic reports that found no signs of pathology. It omits the fact that she remained in the BAYS freely for decades, long after others had left, and that she consistently denied being a victim.

This selective storytelling is not journalism; it is advocacy. It seeks to rewrite history by erasing inconvenient facts and elevating ideological narratives. It treats trauma as a rhetorical device, not a clinical reality. And it does so at the expense of truth.

The attempt to reframe V.L.’s story is not just a personal tragedy but a political act. It reflects a broader effort to use the language of trafficking and abuse to target spiritual minorities. It exploits vulnerable individuals to advance ideological agendas. It also undermines the principles of justice that the 2000 ruling sought to uphold.

Obviously, I do not argue that the BAYS should be above scrutiny—no organization is. But scrutiny must be based on evidence, not emotion, on facts, not fear. The 2000 case was one of the most thoroughly examined in Argentine legal history. To revisit it now, without new and compelling evidence, is to put justice itself on trial.

As this series concludes, one truth remains clear: the Buenos Aires Yoga School was acquitted in 2000 not because of pressure, ideology, or sentiment—but because the evidence did not support the accusations. That decision, rendered by a seasoned judge, deserves to be remembered and respected.

The current case, built on revisionism and ideological fervor, threatens to undo that legacy. It weaponizes trauma, distorts memory, and criminalizes difference. It is not a pursuit of justice but a repetition of error.

The judges who will decide the second BAYS case would do well to resist the ghosts of revisionism, defend the integrity of the past, and remember that justice, once rendered, is not a suggestion. It is a foundation.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.