The judge’s reconstruction of the experience of a young woman whose father started the case was crucial in his decision to declare the defendants innocent.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 2 of 3. Read article 1.

Few cases in Argentine legal history have been as polarizing—or as misrepresented—as that of the Buenos Aires Yoga School (BAYS). Judge Roberto Corvalán de la Colina’s 2000 ruling, which acquitted the School of all charges, was not merely a legal decision. It was a moment of reckoning with the dangers of ideological prosecution and the fragility of personal testimony under public pressure.

At the origin of that case stood one woman. For ethical reasons, and in contrast to some media outlets that have published her full name, we will refer to her only as V.L. Her testimony, psychological evaluations, and life trajectory offer a window into the human cost of misjudgment.

V.L. was not a typical student. By the time she joined the BAYS, she had already endured years of trauma. In her testimony for the case decided in 2000, she recounted being physically assaulted by both her mother and her stepfather. She described the BAYS not as a place of coercion but of refuge. “Since she joined the School, she felt better,” the court record states. She explicitly denied the existence of sexual abuse within the School, contradicting the central claims of the prosecution.

Her testimony was not taken at face value. Multiple professionals, including María Cristina Vila, a specialist in family violence, corroborated it. Vila conducted four in-depth interviews with V.L. in 1999, each lasting two hours. Drawing on these sessions, previous reports, and materials provided by V.L. herself—including videos—Vila concluded that V.L. had suffered psychological, physical, and sexual abuse in her childhood and adolescence. She even used the term “incest.” Crucially, Vila rejected the notion that V.L. had been “brainwashed” by the BAYS. Like Judge Corvalán, and unlike mainstream scholars of new religious movements, she believed in the existence of “brainwashing,” yet she found no evidence of it.

Other professionals echoed Vila’s findings. María del Carmen Pérez de Caputo, who treated V.L. between the ages of 15 and 17, noted her depression and her fraught relationship with her stepfather. While she did not mention sexual abuse, she identified a deep trauma stemming from the separation of V.L.’s biological parents and her mother’s new relationship. V.L. perceived her stepfather as an obstacle to maternal affection—a dynamic that shaped her emotional landscape.

Even V.L.’s half-brother, M.P.S., who opposed her involvement with the BAYS, reinforced her narrative. He described a “familial intervention” (in fact, an attempted deprogramming) orchestrated by their parents and a psychologist named María Lourdes Molina, affiliated with the anti-cult group SPES. This deprogramming attempt led V.L. to leave her maternal home, with the help and escort of the police. M.P.S. also revealed that V.L. had attempted suicide three times before joining the BAYS and struggled as a student. She did not refer to her stepfather as “papá,” underscoring their emotional distance.

These testimonies painted a consistent picture: V.L. was a young woman escaping a toxic home environment, not a victim of spiritual exploitation.

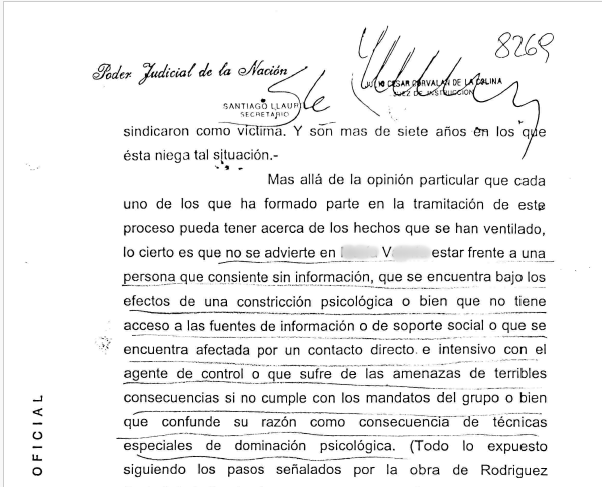

Judge Corvalán de la Colina’s analysis of V.L.’s case was meticulous. He found no signs that V.L. had been manipulated. “Facing V.L., we do not perceive her as somebody who is persuaded easily without being informed,” he wrote. She was not under psychological constraint, lacked no access to social support, and was not subjected to threats or intensive control, Corvalán concluded.

The judge emphasized that V.L. had improved since leaving her home. Her suicide attempts ceased, and she remained committed to the BAYS for years, long after others had left. “In so many years, she might have changed her opinion,” Corvalán noted. But she hadn’t. She insisted she was not a victim of the School.

The prosecution’s suggestion that BAYS had molded her into a brainwashed “adept” was dismissed. “Of this there is no convincing evidence,” Corvalán wrote. V.L.’s own statements undermined the claim. A forensic medical examination conducted in 1994 found no signs of severe pathology or personality change. What it did reveal was a pattern of depression and familial conflict.

For over two decades, V.L. maintained her position. She continued to live independently, worked in BAYS’s cafeteria, and rejected the accusations made by anti-cult activist Pablo Salum—accusations that included her name. Her consistency was remarkable, especially given the media pressure and social stigma surrounding the School.

Her story, as told in 2000, was not one of victimhood but of survival. She had found in the BAYS a community that respected her autonomy and supported her healing. The psychologists who examined her did not find a manipulated follower—they found a woman reclaiming her life.

Prosecutors, the media, and V.L. herself are challenging that narrative in 2025, as we will detail in the next (third) article of this series.

The attempt to reframe V.L.’s story is part of a broader effort to revisit the 2000 decision. The new case against BAYS relies heavily on testimonies and theories that have already been examined and dismissed. The new BAYS case is part of a broader trend in Argentina, which blurs the line between protection and persecution, turning therapeutic language into prosecutorial tools. In V.L.’s case, the danger is not just legal but personal. Her life, once a testament to resilience, is now being used to undermine the very community that helped her heal.

V.L.’s story, as told in 2000, was one of pain, escape, and recovery. It was validated by experts, upheld by a judge, and sustained by her words for over two decades. Her recent reversal must be approached with caution. The stakes are too high—and the history too clear—to allow emotion to override evidence.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.