Religion (including the presence of a Polish Pope) was not the only factor leading to the fall of Eastern European Communism, but certainly played a role. There were also religious consequences, from Russia to China.

by Massimo Introvigne*

*A paper presented at the event “From the Fall of the Berlin Wall to the Unification of the Two Germanies: End of the Cold War,” organized by Rotary Club Castelfranco di Sotto and E-Club Distretto 2071, San Miniato (Pisa), January 10, 2025.

I belong, like some others in this room, to the generation that grew up believing we would never see the end of the Soviet bloc and the Cold War. As there were the Sun and the Moon, so there were the Communist Bloc and the Free World; and in Italy, there were the Communist Party and the Christian Democrats.

Yet, contrary to my expectations, we did see the end of Communism in Eastern Europe and the end of the Communist-Christian Democrat bipolarism in Italy, which compelled us to think in entirely different political terms. There are now entire libraries on the end of the Soviet Union and the Cold War. I am, by trade, a sociologist of religions. Rather than offering general comments about these momentous events, I will confine myself to four aspects that have a connection with my specialized field: the role of religion in the fall of Eastern Communism, the religious consequences in Russia and Eastern Europe, the religious consequences in Western Europe, and the effects on China (a country of which I also happen to be a specialist).

First, we will certainly not solve tonight the question of the reasons of the fall of Soviet Union, the Berlin Wall, and Eastern European Communism. It is a matter of heated debate between historians. Four main reasons are mentioned. First, the economic crisis of the Soviet Union. Ultimately, we should acknowledge that socialism is a less effective economic system than capitalism and as modern economy advanced, socialism was simply unable to cope. Second, the action of American President Ronald Reagan exacerbated the Soviet economic problems with his Star Wars program. Russia could cope with this new American military threat only by spending enormous sums of money it did not have.

Third—and here we start entering the field of religion—there was the Soviet defeat in Afghanistan in 1989, after ten years of bloody war. The Soviet Union was not accustomed to losing wars. It lost the one in Afghanistan not only (as a certain narrative would have us believe) because the United States helped its enemies but because the Kremlin strategists largely lacked the theoretical and cultural tools to understand a new and unforeseen global actor, Islamic fundamentalism. Fourth, it is alleged that the fall of the Communist Eastern bloc was due to the pressure of civil society in some countries, starting from Poland, where it was organized by the Catholic Church and fueled by the election of a Polish Pope, John Paul II, in 1978.

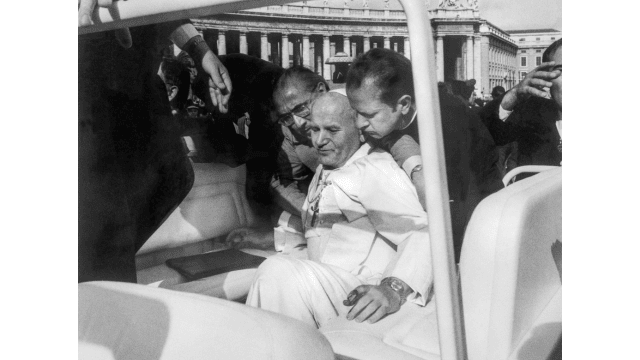

I am aware that historians are divided on this fourth cause of the events we are discussing. For some, it is the single most important cause. The Soviet Union started to fall the evening John Paul II was elected. For others, it was not so crucial. This is another debate we will not solve tonight. One aspect worth noting is that the Soviets themselves regarded the Polish Pope as a serious threat, so much so that they tried to assassinate him in 1981. There are now enough documents to confirm that the assassination attempt against John Paul II was organized by the Soviet and other Eastern European secret services. As we know, it failed, and the Pope continued in his support for the Polish workers’ movement and its resistance to the regime, which eventually set in motion a chain of event fatal to Communism in Poland and in other countries.

Lithuania is another example of a country where the Catholic Church was the soul of the struggle for independence and the end of the Soviet occupation. And in turn the events in Lithuania were crucial for the collapse of the whole Soviet Union.

The action of the Catholic Church and John Paul II alone would probably not have destroyed the Soviet Union and its system of satellite states without the defeat in Afghanistan and the economic crisis. But it was a powerful co-cause of what happened.

The second theme I would like to mention is the religious aftermath of the fall of Communism in Russia and Eastern Europe. Immediately after the demise of the Communist regimes, there was a visible religious revival almost everywhere. Taking advantage of the restored religious liberty, people queued to be baptized. Many churches were full. Even new religious movements such as the Hare Krishna and some Pentecostal churches enjoyed considerable success. However, this phenomenon was short-lived. Soon, as it would not have been difficult to predict, Westernization generated secularization. In Poland, the number of those who attend Mass is still more than double than in Italy but it is quickly declining. It was once above 50%; it is now under 30%. In Lithuania, it was 16% before COVID and some believe it went to 5% after COVID.

Russia has seen a spectacular decline. We cannot compare weekly attendance to Mass in Russia with Poland or Lithuania because Catholics have an obligation to attend Mass every Sunday and Orthodox don’t. Yet, while the most important liturgical day for the Orthodox Church is Easter, Christmas had become increasingly popular. In the last available statistics, for 2023, only 2% of Russians went to church at Easter and only 1% at Christmas.

The reasons of this decline are twofold. First, in countries such as Poland and Lithuania (much less in Russia), Christian churches were seen as the soul of the country and the bastion of resistance against Communism. Going to Mass was also a political statement. With the end of Communism, this political function disappeared. Or perhaps it didn’t, it went through a change. Although there are exceptions, many bishops and priests in Eastern Europe, both Catholic and Orthodox, are nationalist and morally and politically conservative. In Russia, of course, Patriarch Kirill and the Orthodox establishment are pillars of the Putin regime and staunch supporters of the war of aggression against Ukraine. While these positions of strong identification with the governments, or with some political parties, granted economical advantages to the churches, again particularly conspicuous in Russia, they alienated a part of the population and a good portion of the younger generations. If there was an Eastern European religious revival after the fall of Communism, it seems it came to an end.

My third subject is that a similar phenomena also happened in Western Europe. There, it existed a “cultural Christianity” that was perhaps not based on deep spiritual persuasions and a strong faith but on a process sociologists call identification. In a polarized world, exhibiting some Christian traits and practices affirmed that we were “us,” i.e., part of the Western world, as opposite to “them,” the Communist East. In Italy this had deep political consequences, as it justified the Christian Democrat system of power. Once the Cold War ended, this form of cultural Catholicism or cultural Christianity had no reasons to continue. This was not the only and perhaps not even the main reason of the decline in church attendance in all Western European countries but was one of them. To appreciate the phenomenon, we should take with a grain of salt statistics such as the one produced by ISTAT in Italy that are based on telephone surveys. They measure how many Italians “say” they go to Mass weekly when asked by a telephone interviewer. As sociologists know, this number is different from those who really go to Mass, counted at the door of the churches. While ISTAT statistics mention an unrealistic 30%, the pre-COVID effective data obtained through church door counting in representative dioceses was around 18% before COVID and may have declined under 10% after COVID. In Germany 5% of Catholics regularly went to Mass in 2024. The number of Protestants attending religious services was even lower. Surely, even many who rarely go to Mass keep forms of Catholic “identity without identification.” However, in Italy as elsewhere, the end of the Cold War (and in Germany the fall of the Berlin Wall) was a factor of secularization of religious practice (which is not necessarily a demise of religious belief).

My fourth subject, as a scholar inter alia of China, is how what happened in Eastern Europe affected the Chinese Communist Party. This has a lot to do with religion. Xi Jinping is the leader of a generation of Communist leaders who emerged by studying in Chinese Party schools the reasons why Communism fell in Russia and Eastern Europe. For them, it was a question of life and death. How to avoid that China would go the same way of the Soviet Union and get rid of the Communist Party? Some of them even went to Eastern Europe to see things with their own eyes and produced voluminous reports, which had a crucial importance in shaping Chinese policy in the 21st century. These reports embraced the fourth of the four explanations of the end of Communism in Eastern Europe I have mentioned before. They concluded that the fall was due to an excessive liberty left to civil society and in particular to one segment of it, religion, particularly in countries such as Poland and Lithuania, as well as in some Muslim parts of the Soviet Union. Since the Communist Parties failed to eradicate religion, in the end religion eradicated the Communist Parties.

Let me insist that I am not arguing that this interpretation of the events in Eastern Europe is correct. Perhaps it is not. But this is not important for China. What is important is that the new generation of Chinese leaders, the generation of Xi Jinping, believed it, because this belief generated social and political consequences. While after the death of Mao a limited religious tolerance (emphasis on “limited”) was introduced by Deng Xiaoping, and more or less continued by his successors, Xi Jinping has introduced a much stricter surveillance of all religions that becomes tougher with every new regulation on religion, and there is one almost every year. Propaganda of atheism, which was languishing, has also been revamped. The main reason of this different attitude of Xi Jinping with respect to leaders of an older generation is that the defining experience of his formation as a Communist Party bureaucrat was having to confront and interpret what had happened in Russia and Eastern Europe. Since the prevailing orthodoxy in China is that giving free rein to religion in Poland and beyond had been the beginning of the end for European Communism, reining religion in, including Islam in Xinjiang, has become a priority for Xi Jinping.

I have mentioned four themes—the role of religion in the fall of Eastern European Communism, the short-lived post-Communist religious revival in Russia and Eastern Europe and its decline, the crisis of cultural Christianity in Western Europe, and a stricter control of religion in China based on a certain interpretation of the events in Europe. These four themes certainly are just a small part of the premises and consequences of the events we are discussing tonight. But they show that also for sociologists of religions these events are crucial to understand the deep transformations of our world.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.