The most visited exhibition of 2024 in Italy offers an opportunity to revisit the Norwegian painter’s interests in Spiritualism, Theosophy, and the demonic.

by Massimo Introvigne

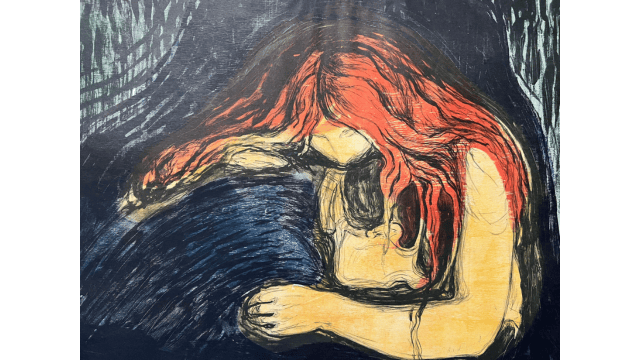

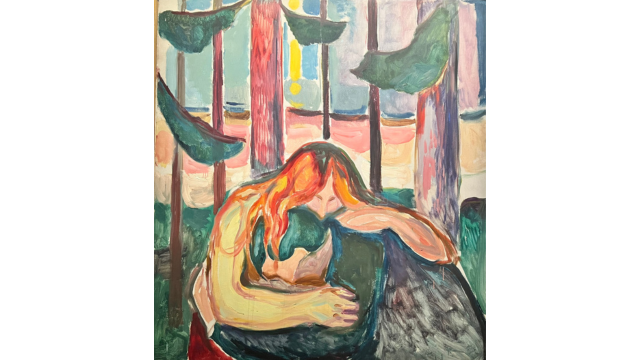

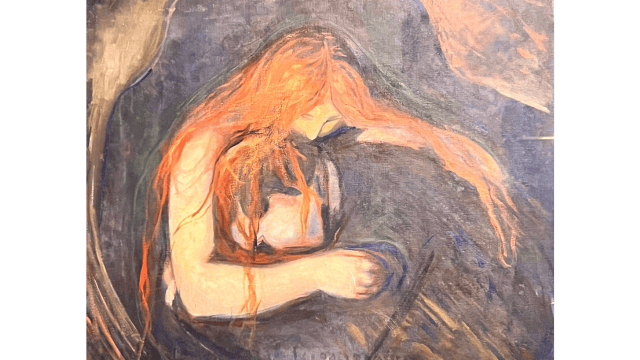

As 2024 comes to an end, the most visited exhibition in Italy has been the one consecrated to Edvard Munch (1863–1944) at the Royal Palace in Milan (open until January 26). “The Scream,” too important to attract visitors there, has remained in Oslo, but most of the other crucial works by Munch did travel to Milan, including all four versions of “The Vampire.”

The exhibition does not focus on the esoteric connections of Munch but does not ignore them either. We are well informed about these connections thanks to several articles of Per Faxneld and the doctoral dissertation of Deniz Beyhan directed by Linda Darlymple Henderson at the University of Texas at Austin in 2016.

The young Munch was exposed to Spiritualism, then something new in Norway, through his association with his language teacher, Hendrik Storjohann (1840–1915), the man largely responsible for introducing the movement to Oslo (then called Christiania), and Erik Fredrik Barth Orn (1828–1899), the vicar of the church attended by his family.

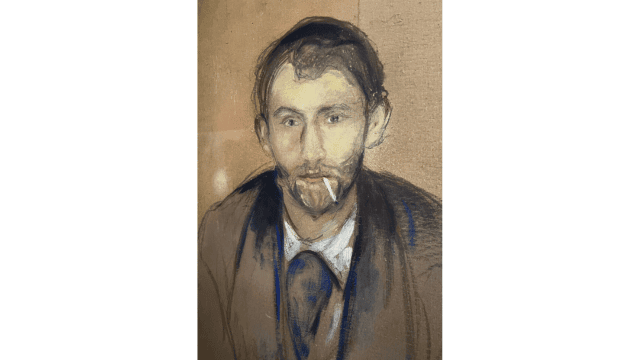

After a state-funded trip to Paris in 1889, Munch arrived in Berlin in 1892, where he developed a decisive friendship with Polish novelist Stanisław Przybyszewski (1868–1927: his portrait of the Polish author is exhibited in Milan). He has been studied by Faxneld as the man who “formulated what is likely the first attempt ever to construct a more or less systematic Satanism,” and in this sense “the first Satanist,” even if Przybyszewski either did not care or was not able to build an organized Satanist group around him.

Przybyszewski was born in Łojewo, in North-Central Poland, on May 7, 1868. After high school, he went to Berlin, where he studied architecture and medicine. He lived with Marta Foerder (1872–1896), by whom he had three children. He left her and married Norwegian writer Dagny Juel (1867–1901), famous as the model for several important paintings by Munch.

Przybyszewski had another two children by Juel, but theirs was a very open marriage. Both had several affairs, and Juel was assassinated in 1901 by a man some claimed was her lover. In 1896, Foerder had also died of carbon monoxide poisoning in Berlin. Przybyszewski was arrested and accused of her murder, although he was ultimately exonerated. By then, he had already published both fiction and philosophical texts, including the successful trilogy of novels “Homo Sapiens,” and started being recognized as a relevant voice within the new generation of revolutionary and modernist Polish writers.

It is in the middle of these circumstances that in the mid-1890s in Berlin Przybyszewski emerged as the key member of the international group of artists gathering at the tavern Zum Schwarzen Ferkel (The Black Piglet), which included Danish playwright August Strindberg (1849–1912), Munch, the Finnish painter Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865–1931), and the Norwegian sculptor Gustav Vigeland (1869–1943). Przybyszewski regularly discussed esotericism and art with the group.

According to Faxneld, it was Przybyszewski that gave to Munch’s painting originally called “Love and Pain” the title “The Vampire,” under which it became internationally famous, thus radically changing “an image that, according to the artist, originally had nothing to do with the supernatural and demonic.”

It might, however, have had something to do from the beginning with Munch’s fear of sexual relationship with women as depriving men of their vital essence, sperm, in itself an esoteric theme in addition to one that complicated his main romantic relationship, with Mathilde “Tulla” Larsen (1869–1942).

In 1902, within the bedroom of Larsen’s residence, an argument escalated, resulting in gunfire. During the altercation, Munch sustained a bullet wound to his left hand, and what exactly happened was never clarified.

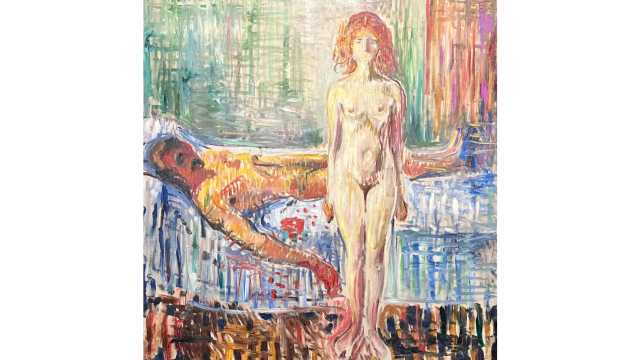

In 1907 Much painted “The Death of Marat,” paying homage to the famous painting with the same title by Jean-Louis David (1748–1825) but also representing himself as Marat and Tulla Larsen as Marat’s assassin.

The theme of the woman as dangerous temptress had already emerged in Munch’s 1894 controversial “Madonna,” where the model was Przybyszewski’s wife Dagny Juel. It was also one of the paintings that put Munch at odds with Norwegian censorship.

Beyhan reports that Przybyszewski involved Munch in psychic experiments and Spiritualist seances (something the Norwegian artist had already encountered in his home county) and shared with him occult and Theosophical literature.

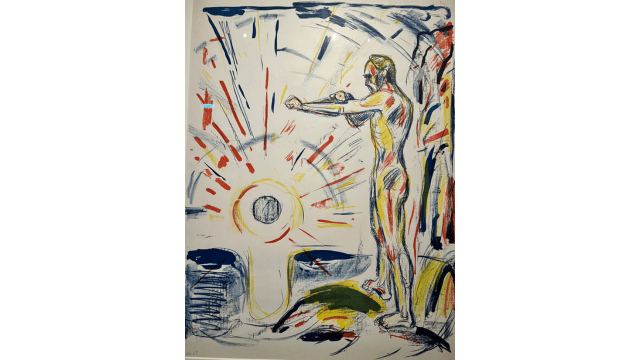

Munch’s interest for esoteric currents other than Spiritualism predate his arrival in Berlin. Greatly admired by Przybyszewski , “Vision,” which according to the curators of the Milan exhibition, Munch regarded as his most important painting and one superior to “The Scream,” already reveals his exploration of occult themes. It was painted shortly before he moved to Berlin.

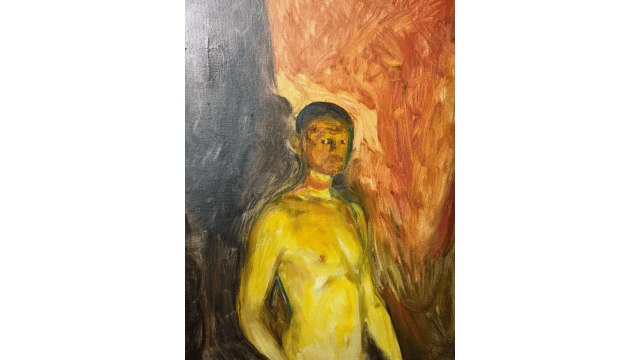

After the encounter with Przybyszewski, the demonic continued to appear in Munch’s work. His celebrated 1903 “Self-portrait in Hell,” also part of Milan’s exhibition, is the testimony of a personal crisis but also reveals a continuing engagement with demonic themes.

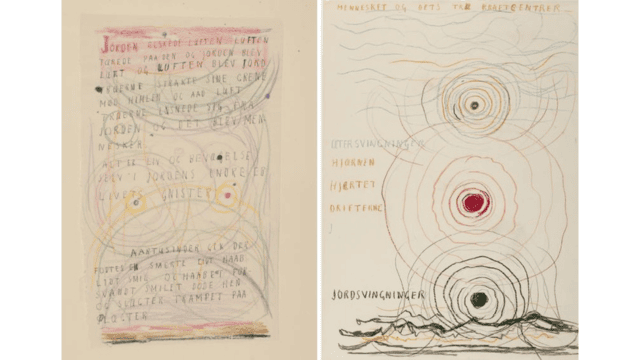

Strindberg also developed an interest in occult and parapsychology, and Munch joined him again when both were in Paris in 1896. With the new century, Beyhan sees Munch’s esoteric interests increasingly switching from Spiritualism to Theosophy, finding evidence of Theosophical influences in the late sketchbook “The Tree of Knowledge” (1930–35) and murals, although the influence of the monism of Erns Haeckel (1834–1919) also appeared.

An iconographic analysis, including of the different paintings titled “Towards the Light,” also reveals the presence of Theosophical themes.

Esotericism, Spiritualism, Theosophy, and demonic themes derived from Przybyszewski were not the only keys of Munch’s work. But they are an integral part of it.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.