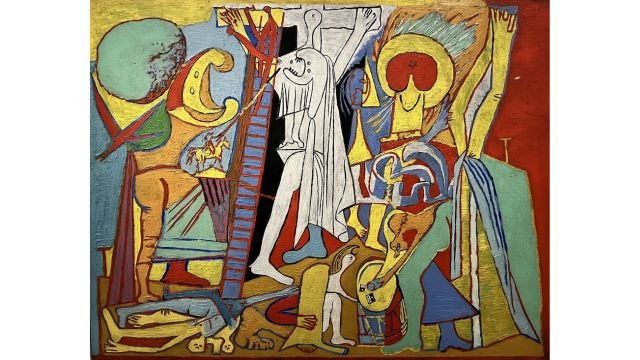

A great and difficult work, it has been called “a blind spot in Picasso scholarship.” What does it really have to do with religion?

by Massimo Introvigne

I was recently at Paris’ Picasso Museum for the Pollock exhibition, but I could not resist going to see again one painting of the permanent collection whose surprises are never exhausted, Picasso’s 1930 “Crucifixion.”

Art historian Charles F.B. Miller has called it “a blind spot in Picasso scholarship”: “it gets reproduced in color and large format, it has been the centerpiece of exhibitions, the literature in general extols it as exceptional; yet, in the scant commentary, timorousness undercuts the lofty claims, historicism defers to ‘Guernica’, discourse lapses without self-criticism.”

Basically, there are two irreconcilable interpretations of the painting. In an influential article published in 1969 in “The Burlington Magazine,” another art historian, Ruth Kaufmann, asked whether the work is really “as enigmatic as most authorities have claimed it to be.” Her answer was that it is not enigmatic at all and has very little to do with Christianity. Picasso depicts human cruelty and sadism by amassing in the paintings references to “primitive religious practices” and to something he was interested in, the worship of Mithra.

At the opposite extreme of the critical debate, Jane Daggett Dillenberger and John Handley, who are both art historians and theologians, in “The Religious Art of Pablo Picasso” (University of California Press 2014) see in “Crucifixion” one of Picasso’s works that are “profoundly Christian insofar as the Christian narrative resonates in the paintings and drawings.”

I am not a Picasso scholar but believe the truth is somewhere in the middle. There is no doubt Picasso was an atheist. On the other hand, as Dillenberger and Handley note, like almost every artist of the 20th century he could not ignore centuries of Christian imagery and indeed was fascinated by it. Several critics have seen in “Crucifixion” reminiscences of Grunewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece, perhaps even citations.

Yet, “Crucifixion” does not entirely follow the Christian narrative of the death of Jesus. Picasso knows the traditional iconography of the Crucifixion but is not interested in reproducing it. He seems more interested in the context and in the other characters than in the Christ. This is why he takes several liberties with the Evangelical narrative.

Not that interpreting the figures in the painting is easy. Almost everything is conjectural and disputed. For instance, we know from the preparatory drawings for the painting that Picasso was interested in including Mary Magdalene. But where is she? She has been seen in different parts of the work, perhaps because Picasso has represented her twice, a possible allusion to her duality as saint and sinner. Several critics agree that the Magdalene is the white figure with a claw-like mouth on the cross. If we assume that she is licking the blood from Christ’s wounds, this has precedents Picasso surely knew in Medieval imagery and devotion. Christ’s upper wounds were compared to a lactating breast. Both give life, the latter in the material and the former in a spiritual sense.

But the Magdalene has also been seen in the tall figure resembling a praying mantis on the right. Her dramatic attitude both connects Earth and Heaven and cries in desperation.

Some traditional characters are more recognizable. We see on the right a drum with dices, and figures of the soldiers who “gambled for Jesus’ clothes by playing dice” (Matthew 27:35), although the expressive white figure on the left of the drum has also been identified with John the Baptist. On the left, at the foot of the ladder, are the contorted bodies of the two thieves. The two small t-shaped crosses on the left and the right are the empty crosses of the thieves.

Higher up, on the left of the ladder, we see Longinus with his spear represented as a Spanish picador, which supports the idea that Picasso compared the sacrifice of Christ to the sacrifice of the bull in the corrida and perhaps in ancient rituals. There is a character on the latter driving a nail on Christ’s arm, and the huge shape in the upper left hand corner may be the sponge of the vinegar.

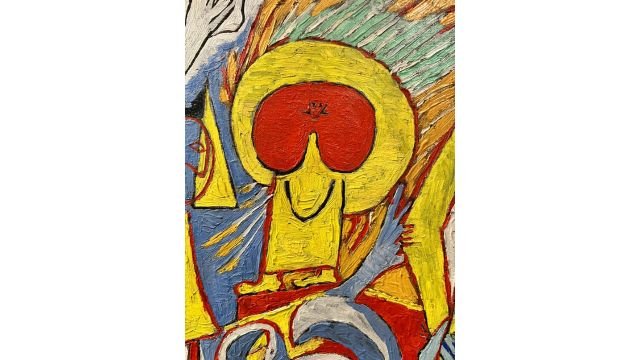

Other characters are indeed enigmatic. There are all sorts of interpretations for the huge figure on the left of the cross, and even more for the vaguely caricatural one on the right of the same cross, the yellow-red character with deformed head and body, yet recognizable as human by the feet. It has been interpreted as the risen Christ, as a humanized skull (from which the Golgotha was named), and even as a sexual allusion.

Between this figure and the cross there is another character difficult to read, with a blue female face above what looks like a yellow dress. Some see here the Virgin Mary, although all these characters have also been interpreted as astrological allusions.

Paradoxically, much less discussed is the Christ himself. I believe there is a reason for this. It is not the real center of the composition. Picasso does not have much to say about him, and for this reason this cannot really be called a Christian painting—a conclusion for which Picasso’s biography would not be an insurmountable obstacle, as the history of art is full of Christian images produced by non-Christians.

I am not inclined to follow Dillenberger and Handley in calling the painting “profoundly Christian.” On the other hand, it “is” a Crucifixion, not a Mithraic rite or a catalogue of “primitive” rituals. It is, simply, “another” Crucifixion, a non-Christian gaze on a Christian theme. One Christians can engage with, yet cannot, I believe, claim as their own.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.