Visitors to the important Paris exhibition would not learn about his esoteric connections. But they can find them in his paintings.

by Massimo Introvigne

The Paris exhibition “Jackson Pollock: The Early Years (1934–1947)” at the Picasso Museum in Paris, which closes on January 19, is a notable achievement with an agenda. This is, after all, the Picasso Museum and the curators want to attract the attention on the young Pollock’s relationship with Picasso. He struggled to be different from the Spanish artist, yet he was also influenced by him.

Visitors would not be clearly exposed to Pollock’s relationship with esotericism, a controversial theme in studies about the American painter and one he was himself aware should be handled with care.

In 1928, when Pollock was 16, his family relocated to Los Angeles, and he attended Manual Arts High School. Pollock initially learned art at Manual Arts. His teacher was Frederic John de St. Vrain Schwankovsky, a modernist familiar with the art of Cézanne and Matisse. In the same year 1928, Schwankovsky had become a member of the Theosophical Society. Through his connections, Pollock was introduced to Theosophy and the teachings of Krishnamurti and attended Krishnamurti’s camp meetings at Ojai. Schwankovsky was also a member of the Theosophy-connected Liberal Catholic Church.

As he wrote to Francis V. O’Connor, Schwankovsky “introduced students to the ideas not only of Krishnamurti, who was a personal friend, but also of Hinduism, reincarnation, karma,” and taught them “how to expand their consciousnesses.”

There are no visible allusions to Theosophy or Krishnamurti in the early works of Pollock displayed in Paris. However, the “expansion of consciousness” idea probably played a role in making him sensitive to Surrealist automatic writing and Jungian psychology.

The context to be considered is the dual relationship between Pollock and two very different characters of the American artistic milieu, art critic Clement Greenberg and painter and collector John D. Graham. The relationship has been studied in an article of 1998 by Elizabeth Langhorne. A formalist and positivist, Greenberg had little patience for esoteric and spiritual themes. He supported Pollock but dismissed any reference to spirituality as a peculiarly American deviation. Pollock was aware of the crucial importance of Greenberg’s support. When he discussed spiritual experiences with friends, he recommended they do not mention them to Greenberg.

Pollock’s relationship with Graham, a Ukrainian aristocrat whose real last name was Dombrowski, was an entirely different matter. The two met in 1940 and became great friends. Pollock later stated that Graham was the only one who had understood him. What attracted Pollock to Graham, Langhorne wrote, were the latter’s “esoteric ideas that Greenberg so disliked” and that reminded the former of his juvenile experiences with Krishnamurti and Theosophy. Graham’s interests included “Theosophy, hatha yoga, tantric yoga, numerology, systems of proportion derived from Pythagorean and Platonic sources, alchemy, and astrology.”

Graham, however, also appreciated Picasso and the Surrealists and encouraged Pollock to engage with them and experiment with automatic scripture and Jungian themes.

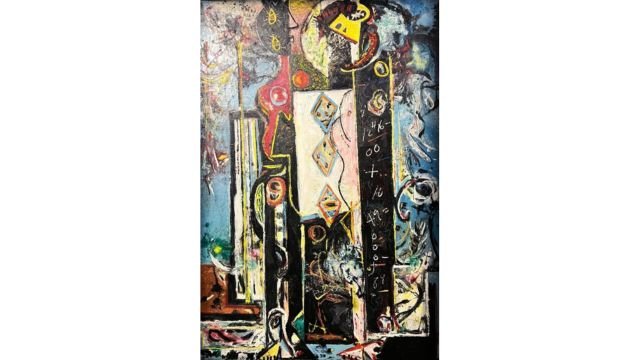

All this happened before the dippings that made Pollock internationally famous and is at the center of the Paris exhibition. A key painting there is “Male and Female” (1941–42). The exhibition insists on Picasso’s 1932 “Woman and the Mirror” as a possible source of inspiration but also acknowledges that at the time Pollock was reading Jung and represented there the Jungian presence of both feminine and masculine aspects in all individuals.

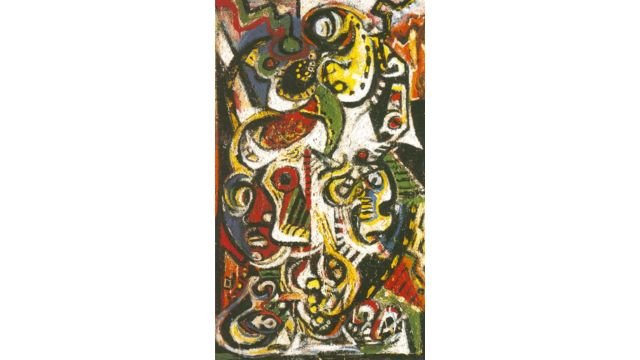

Langhorne would see here also alchemical references. She mentioned “Masked Image” (1938–41), also on display in Paris, as a passage between Picasso’s “Woman at the Mirror” and Pollock’s “Male and Female,” which introduces spiritualist and alchemical allusions absent in Picasso’s work.

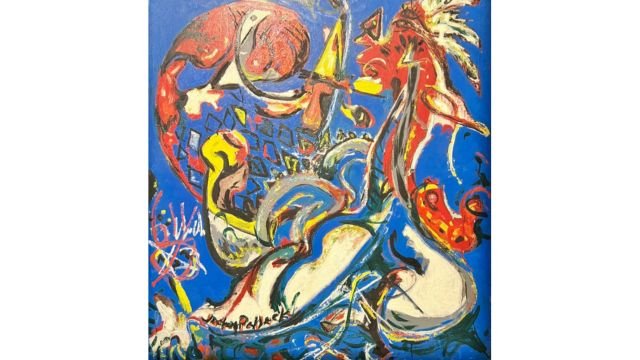

One point the Paris exhibition emphasizes is the importance of Pollock’s visit to 1941 New York MOMA exhibition “Indian Art in the United Nations.” He went there with Graham. He started drawing on Native American myths but also inventing a mythology of his own, rooted in his early esoteric experiences, as evidenced by “The She-Wolf” (1943) and “The Moon Woman Cuts the Circle” (1943). Of course, echoes of “Guernica” are also there, and of Surrealist automatic paintings (which these works of Pollock are not).

Mentioned in the Paris exhibition is also the artistic conversation between Pollock and the Mexican muralists, emerging in works such as the 1938–41 “Untitled” inspired by Orozco. As I have documented elsewhere, with all their Marxism the Mexican muralists were not uninterested in esotericism.

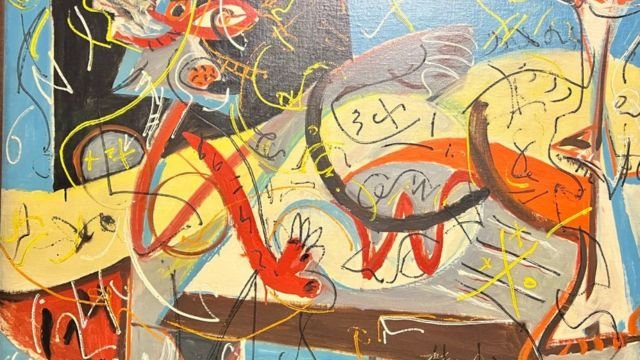

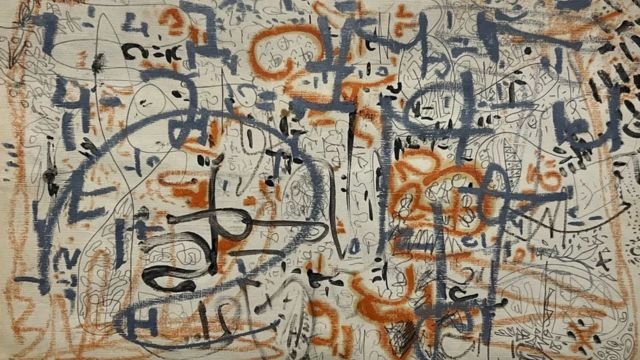

Another important piece exhibited in Paris is “The Key” of 1946. “Guernica” is there, again, but so is a discernible candle-holding woman and other more enigmatic figures that are purely Pollock’s (or perhaps Graham’s).

With “The Key,” Pollock was already transitioning to his signature style, as evidenced by works such as “Red Composition” (1946) and “Table Set” (1946–47). But the Pollock of the origins represented by these Paris paintings never really disappeared.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.