Causes include the lack of scholars sympathetic to new religious movements and the post-Cold War political situation.

by Shunsuke Uotani

Article 3 of 3. Read article 1 and article 2.

One of the unique aspects of the situation surrounding the Unification Church issue in Japan is that there are no scholars of religion who conduct objective research on the church and make neutral statements about it. To put it simply, there are no scholars like Eileen Barker, who conducted participant observations, studied the Unification Church, and was able to disseminate accurate information.

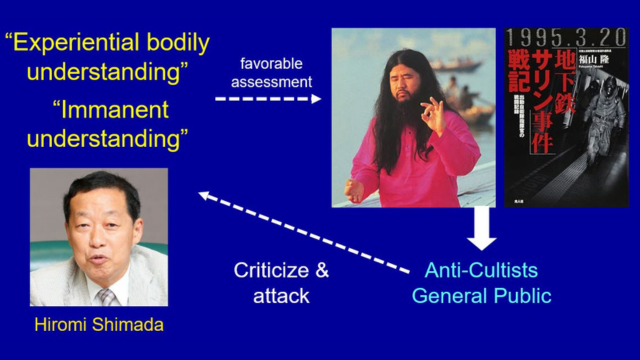

In the history of Japanese religious studies, there was a time when methods like participant observation, called in Japan “experiential and embodied understanding” of believers, and “immanent understanding,” which aims to empathize with the inner world of believers, were popular. This was driven by the goal of overcoming the divide between researchers and their subjects and bringing the two closer together. Both approaches demonstrated a very positive attitude toward the world of religion.

However, scholars of religion who used these methods to study Aum Shinrikyo faced criticism for missing the darker sides of the movement, and these research methods were criticized as being “too positive about religion,” which caused a significant setback. The trauma the Aum incident left on the study of new religions in Japan is so deep that it is no exaggeration to say it has not yet recovered (Uotani, “Rebuttal to Yoshihide Sakurai and Hiroko Nakanishi’s book ‘The Unification Church,’” pp. 751–52).

It has become very challenging for Japanese scholars to maintain a proper distance from controversial new religious groups in this situation. Even when academic research is conducted with appropriate detachment, it’s hard for the general public and anti-cult groups to see it as having maintained an “appropriate distance.”

Hiromi Shimada, a professor at Japan Women’s University and a scholar of religion, was suspended from the university after the Tokyo subway sarin gas attack due to his past favorable assessment of Aum Shinrikyo and was eventually forced to resign.

Similarly, if a Japanese scholar of religion studied the Unification Church to gather information and then wrote an impartial account, opponents might criticize him with comments like “You’re too sympathetic to the Unification Church!” or “You’re a poster boy for the Unification Church!,” leading many religion scholars to hesitate before starting such research.

In Japan, even religious scholars are expected to be “politically correct,” and academic freedom and independence are almost nonexistent. This was why research on new religions in Japan dropped significantly after the Aum Shinrikyo incident. Society refuses to tolerate research on controversial new religions unless one adopts an openly critical stance.

Finally, I would like to consider why the order to dissolve the Unification Church has been issued now.

The opposition movement against the Unification Church has been persistent over the years and has managed to harm the church’s social reputation. However, no matter how much the Lawyers’ Network urged the Japanese government to dissolve the Unification Church, the government has never seriously tried. This is because neither the Church nor its leaders were charged with a single crime.

What fundamentally changed this situation was the assassination of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe on July 8, 2022. The assassin is not a member of the Unification Church, but his mother is. The panic caused by this incident led then-Prime Minister Fumio Kishida to make an apparent judgment mistake and request a dissolution order without any criminal conviction against the church or its leaders. This is the direct cause of the current situation.

However, there was a historical context for this. The key factor was the end of the Cold War. Hiromi Shimada, who remains one of Japan’s top scholars of religion, examined the Unification Church as a religion rooted in the Cold War period. The theology of the Unification Church, which views world events as a battle between God’s side and Satan’s side and sees communism as being on Satan’s side, was compelling during the Cold War. “Conservative forces and the VOC resonated with each other in terms of developing an anti-communist movement, and in particular, they aimed to criticize the Communist Party domestically and suppress its influence,” he wrote (“A History of Postwar Political Struggles of New Religions,” Asahi Shimbun Publishing, 2023, p. 23).

However, he continues, after the Soviet Union’s collapse in 1991 and the end of the Cold War, the significance of the VOC diminished somewhat for conservative groups, including the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP).

The LDP is primarily a conservative party, but contains more conservative and liberal factions. The Seiwakai, which Abe led, was the most conservative faction with historical ties to the VOC. Abe’s grandfather, Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi, was one of the founders of the VOC and even met Reverend Sun Myung Moon face-to-face in 1973. The Abe family has maintained ties to the Unification Church for three generations.

On the other hand, Kishida’s faction, the Kochikai, is a liberal group that has historically rivaled Abe’s faction, the Seiwakai, within the LDP. At the time of Abe’s assassination, the Abe faction had about one hundred Diet members, while the Kishida faction had roughly forty. Prime Minister Kishida couldn’t run the government without considering Abe’s wishes, so he had a complex relationship with Abe—relying on him but seeing him as a hindrance. This situation changed significantly after Abe’s death.

A local LDP assemblyman analyzed Prime Minister Kishida’s motives for severing ties with the Unification Church and even ordering its dissolution as follows: “When Abe was shot and fell, Prime Minister Kishida was shocked and disappointed. However, he mistakenly thought, ‘This will reduce the influence of the Abe faction. If all goes well, I can eliminate the Abe faction and gain a significant number of members for mine. Or I can weaken the Abe faction.’ I think he aimed to reduce the power of politicians in the Abe faction, especially those who had close ties with the Unification Church” (see Tatsuki Nakayama, ed., “Objections to the Unification Church’s ‘Dissolution Order,’” Good Time Publishing, 2025, pp. 88–9).

The historical anti-UC movement has involved a complicated mix of factors, including religious and ideological motives, as well as parent-child relationships. However, this anti-UC movement did not lead to the dissolution. According to pure legal theory, there is no legal ground for dissolving the Unification Church. The main reason for the move to order the dissolution after former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s assassination was political. The background to the LDP government’s decision to dissolve the Unification Church is that the LDP itself has shifted and become more left-leaning due to Abe’s death and the significant decline of his faction.

Shunsuke Uotani is the secretary general of the Universal Peace Federation-Japan. He studied chemical engineering at the Tokyo Institute of Technology and theology at the Unification Theological Seminary. He has held key positions since the founding of IIFWP, the predecessor of UPF. He has published and lectured widely on brainwashing, mind control, and deprogramming, and has written books such as “Mind Control as Pseudoscience” (2023) and “Rebuttal to Yoshihide Sakurai and Hiroko Nakanishi’s book ‘The Unification Church’” (2024).