The Unification movement’s International Federation for Victory over Communism greatly upset the Socialists and Communists. They reacted.

by Shunsuke Uotani

Article 2 of 3. Read article 1.

The third group comprises left-wing forces represented by the Communist Party and the Socialist Party. Since the Unification Church is a conservative force opposed to communism, they oppose it for ideological reasons. Their opposition is closely tied to the activities of the Unification movement’s International Federation for Victory over Communism (VOC). The left-wing forces, including the Japanese Communist Party and the VOC, are mortal enemies.

The VOC was established in Korea and Japan in 1968. Two years later, in 1970, it began engaging in notable activities, such as supporting the “World Anti-Communist League (WACL) Rally” held at the Budokan, Tokyo, which was highly successful.

The VOC’s anti-communist theory was taught on the streets, and the VOC movement conducted an intense ideological fight against communism on college campuses.

In 1972, VOC sent an “open letter of inquiry” to then-Communist Party Chairman Kenji Miyamoto, proposing an open theoretical debate between the Japanese Communist Party and the VOC broadcast by a TV station.

However, unlike nationalist “right-wing groups,” the VOC criticized communist theory logically and offered alternatives, so the Communist Party considered it a formidable opponent. As a result, the Communists declined the debate, and it never took place (see International Federation for Victory Over Communism, “This Is How the VOC Fought,” Sekainipposha, 2025, pp. 17–43).

In 1978, an “incident” occurred in Kyoto. The communist governor, who had held the position for 28 years, was defeated. The VOC’s election campaign caused this defeat.

In response, Japan Communist Party Chairman Miyamoto stated, “Taking the lead in defeating the VOC is a sacred struggle that will be recorded in the history of future generations” (“Akahata,” June 8, 1978; see “This Is How the VOC Fought,” pp. 43–50).

What further boosted the VOC movement was the campaign to help Japan’s Diet pass an anti-espionage law.

In the 1970s, during the Cold War era, amid US-Soviet détente, the conflict between the free world and communist powers shifted from military clashes to espionage activities. Japan lacked laws to combat foreign espionage, turning it into a “spy paradise” where spies could operate freely.

The VOC actively supported the movement for an anti-espionage law, and by the end of 1986, most local governments nationwide had passed resolutions calling for its enactment. This led to the bill being submitted to the National Diet in November 1986 (“This Is How the VOC Fought,” pp. 88–114).

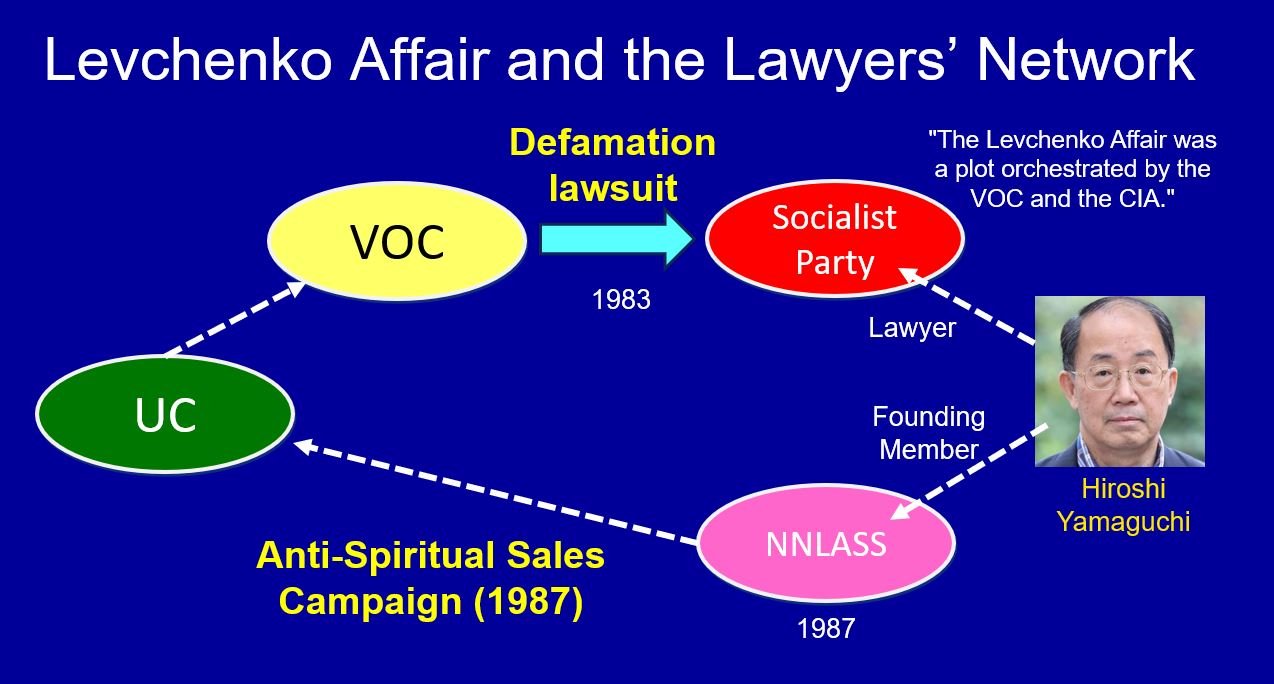

Feeling a crisis about these developments, left-wing forces formed the National Network of Lawyers Against Spiritual Sales (Zenkoku Benren). It was established to oppose the enactment of the Anti-Espionage Law, especially after the “Levchenko Affair.” However, this network of lawyers also aimed to dismantle the VOC and the Unification Church because they supported the Anti-Espionage Law (“This Is How the VOC Fought,” pp. 115–21).

The “Levchenko Affair” involved Stanislav Levchenko, a former KGB major who carried out espionage activities against Japan. In 1979, he defected to the U.S. and testified before the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence about his espionage work. During his testimony, he disclosed the real names and code names of twenty-six Japanese individuals who acted as spies for the Soviet Union, including a top member of the Japanese Socialist Party.

The VOC heavily relied on Levchenko’s shocking testimony and again called for the passage of an anti-espionage law (“This Is How the VOC Fought,” pp. 94–6).

In May 1983, the Socialist Party’s journal, “Shakai Shinpo,” published an article claiming that “The Levchenko Affair was a plot orchestrated by the VOC and the CIA.” Since this was completely unfounded, the VOC filed a defamation lawsuit against the Socialist Party and the editor-in-chief of the party’s journal.

Hiroshi Yamaguchi, who represented the Socialist Party then, later became a key figure in forming the National Network of Lawyers Against Spiritual Sales. This network primarily consisted of attorneys affiliated with the Communist Party and the Socialist Party.

The defamation trial found that the Socialist Party lied about VOC and concluded with a favorable settlement for the VOC. However, as retaliation and an extension of this conflict, the left-wing lawyers increased their efforts against so-called “spiritual sales” by the Unification Church (“This Is How the VOC Fought,” pp. 97–121).

The three groups—Christian pastors, opposing parents, and left-wing forces—collaborated in various ways.

Parents of Unification Church members paid fees to anti-Unification Church pastors for guidance. The anti-UC pastors instructed the parents on specific abduction and confinement methods. Once the parents confined their adult child, the pastors would visit the confinement site and “persuade” the member to renounce their faith.

The parents’ goal was achieved if the members accepted the persuasion and renounced their faith, but this was not the end. Former members were forced to cooperate with anti-UC activities and introduced to left-wing lawyers who persuaded them to file lawsuits against the Unification Church for damages. By representing former members in court, the left-wing lawyers could earn fees while at the same time damaging the Unification Church’s social standing (Uotani, “Rebuttal to Yoshihide Sakurai and Hiroko Nakanishi’s book ‘The Unification Church,’” p. 566).

Additionally, information about these lawsuits was made public through the mass media and used to create anxiety among believers’ parents. This way, the opposition movement became a network of professional groups, including parents, pastors, lawyers, and the media, leveraging their position and skills to corner the Unification Church.

Shunsuke Uotani is the secretary general of the Universal Peace Federation-Japan. He studied chemical engineering at the Tokyo Institute of Technology and theology at the Unification Theological Seminary. He has held key positions since the founding of IIFWP, the predecessor of UPF. He has published and lectured widely on brainwashing, mind control, and deprogramming, and has written books such as “Mind Control as Pseudoscience” (2023) and “Rebuttal to Yoshihide Sakurai and Hiroko Nakanishi’s book ‘The Unification Church’” (2024).