Gauguin’s iconic nativity is also an apology for religious liberty. And we ask you all to support religious liberty this Christmas.

by Massimo Introvigne and Marco Respinti

Dear Readers:

For the seventh time in its history, “Bitter Winter” celebrates Christmas with its loyal readers. Seven years passed quickly. When we started in 2018, we had in mind a magazine dealing with religious liberty issues in China only. It was a niche subject, and we did not expect to have a substantial number of readers. We had a strength, though, our contacts in China and the willingness of several dozens of citizen journalists to risk their liberty to send to us unique stories, pictures, and videos. Some of them indeed went to jail.

Our success went beyond our own expectations. Not only we reached 100,000 unique visitors per month and more, but we also became the most quoted source on religious liberty in China in the yearly reports of the U.S. Department of State for several years in a row. We were also routinely quoted by British, Dutch, Italian, and other governmental reports as a believable and authoritative source on China. This is not due to our being smarter than somebody else, but to the bravery and resilience of our correspondents from inside China.

In 2020, we decided to lengthen our stride and expand “Bitter Winter” beyond China. We started publishing every day one article on China and one on other countries. We also decided to often include a Saturday feature article devoted to the visual arts and culture, always connected with religion and spirituality.

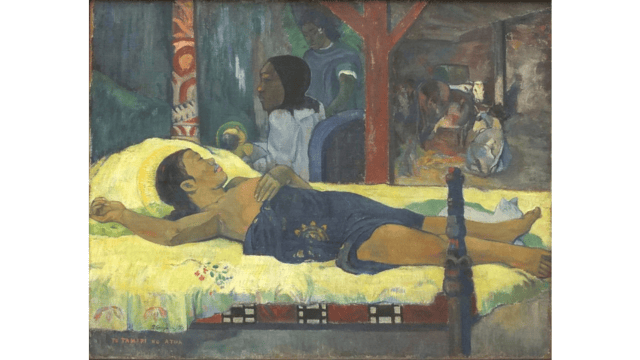

It is by acknowledging that these art articles have gathered a loyal following too that we celebrate this Christmas with a reproduction of “Te Tamari no Atua,” painted in 1896 in Polynesia by Paul Gauguin. “Te Tamari no Atua” can be translated as “The Birth of the Son of God,” or (in the language of the missionaries) “The Birth of Christ, Son of God.”

Gauguin was no friend of the missionaries. Although not a member of the Theosophical Society, he came to Polynesia with the works of Madame Blavatsky in his luggage and shared her criticism of Christian missionaries who lacked cultural sensitivity and tried to eradicate local traditions. Yet, he had known and represented with nostalgia the simple popular Catholicism of the peasants in Brittany, which resonates in his Polynesian nativity.

Mary is a Tahitian woman, who sleeps under a Tupapaù, the totemic pole of life and death in Polynesian indigenous spirituality. The son of God sleeps in the arms of a woman whom Gauguin himself identified as an angel. The classical manger scene is reproduced on the right.

The painting is not significant only because of Gauguin’s usual mastery of colors and shapes. In its own way, it has to do with religious liberty. It calls for respect for different religions: Christianity, which some of Gauguin’s anticlerical friends treated with contempt, and Tahitian spirituality, which some missionaries repressed as “heathen” and perhaps demonic.

It reflects the approach of “Bitter Winter.” Its editor-in-chief and director-in-charge are both active Roman Catholics. We do not feel the need to apologize for this. At the same time, we know that freedom of religion or belief is the first political human right. It is not rooted in the content of what is preached but on the natural right to preach, to worship, to believe, or not to believe. For this reason, “Bitter Winter” defends freedom of religion or belief as a right for all, including unpopular minorities and some whose theology is very much far away from our own.

Not everybody understands or shares these points of view. It is one more reason to give voice to them. It seems from its very success that “Bitter Winter” serves a useful purpose. We repeat it at every Christmas, but the number of donors is still far away from the number of readers. We do appreciate that we are all solicited to give to many worthy causes, and that giving online takes some time and we are all very busy. This is why we continuously try to make giving to “Bitter Winter” simpler. The current average time to complete the online donation form is three minutes.

We are thus not ashamed to ask once again for your three minutes this Christmas. If you read what you like, like what you read, and agree with us that religious liberty is the most important of all political causes, please support us. We need your help. Merry Christmas and may God bless you all.

Massimo Introvigne, editor-in-chief

Marco Respinti, director-in-charge

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.