The twelfth United Nations submission on the Tai Ji Men case confirms Taiwan’s problems with the Two Human Rights Covenants.

by Massimo Introvigne

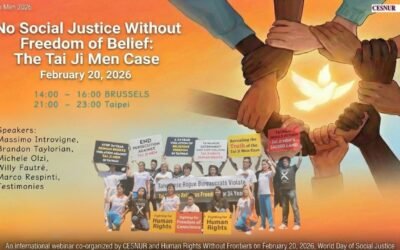

Some cases fade after a news cycle. Others hang on like an unwanted echo. Then there’s Tai Ji Men—a case that won’t leave Geneva’s corridors, regardless of how many years pass or how many Taiwanese authorities insist the issue is “closed.” During the 61st session of the UN Human Rights Council, the ECOSOC-accredited NGO Coordination des associations et des particuliers pour la liberté de conscience (CAP-LC) submitted yet another written statement regarding the ongoing human rights controversy surrounding Tai Ji Men. If the Council felt a sense of déjà vu, it was justified.

This isn’t the first time Tai Ji Men has been brought to the UN’s attention. It is the twelfth. On November 9, 2010, the Association of World Citizens—another ECOSOC-accredited NGO—filed a formal 1503 procedure with the Human Rights Council. They urged the Council to investigate the case due to serious human rights concerns. The 1503 mechanism is not casual; it is meant for chronic, credible claims of violations.

CAP-LC has been equally persistent. Between 2021 and 2025, it submitted ten written statements to the Human Rights Council regarding the Tai Ji Men case. The new statement for 2026 marks the twelfth time this issue has been presented to the world’s highest human rights body. While bureaucratic injustices may take time to age, the memory of civil society does not fade.

This year’s written statement, titled “The Two Covenants, the Abuse of Tax Law Against Spiritual Minorities, and Two Shadow Reports,” is CAP-LC’s most thorough intervention to date. It places the Tai Ji Men case in the broader context of the ICCPR and ICESCR—two covenants that Taiwan, although not a UN member state, voluntarily agreed to implement in 2009. It does this with clarity, cutting through decades of red tape.

Download the full statement in PDF (general distribution date subject to change).

The statement begins by reminding readers that the Two Covenants protect “freedom of religion or belief, equality before the law, law, due process, freedom of movement, of expression and assembly, the right to work, education, an adequate standard of living, and to participate in cultural life.” These rights are at risk “when administrative mechanisms, including taxation, are arbitrarily or unfairly used against spiritual or cultural minorities.” CAP-LC then examines Taiwan’s 2025 national report on these Covenants and two corresponding Shadow Reports prepared by civil society, which once again highlight the unresolved Tai Ji Men case.

The core of the statement calmly describes how a traditional menpai of qigong and self-cultivation became caught in a decades-long administrative maze. CAP-LC details how the National Taxation Bureau (NTB) erroneously classified disciples’ red-envelope gifts as cram-school tuition, issued tax bills without proper investigation or hearings, and continued pursuing the bills even after the Supreme Court ruled that the gifts were tax-exempt. Even after all the other bills were corrected to zero, the NTB relied on a technicality to maintain the 1992 bill. This culminated in the 2020 nationalization of Tai Ji Men’s sacred land—an action CAP-LC points out took place “despite the Control Yuan identifying multiple legal and procedural violations.”

The statement is explicit about the human rights implications. It concludes that the case inter alia violates the principles of equality and non-discrimination (Articles 2 and 26 of ICCPR), the right to due process (Article 14 ICCPR), the right to an adequate standard of living under Article 11 of the ICESCR, and the right to participate in cultural life under Article 15 of the ICESCR. It also alerts that the case shows how unchecked administrative power can be used to suppress spiritual and cultural communities, threatening freedom of religion or belief.

CAP-LC’s analysis doesn’t stop at the past. It points to ongoing structural issues: the reliance on nearly 10,000 interpretive rulings—many from the Martial Law era—that let agencies sidestep legislation, the “perpetual tax bill” problem that traps citizens in endless legal battles, and the lack of independent protections for taxpayers. CAP-LC argues these issues are not just technical flaws but systemic threats to the rights guaranteed by both Covenants.

The recommendations in the statement include: “the immediate revocation of the unlawful 1992 tax bill and the return of the seized land; the abolition of tax and enforcement bonuses that encourage the issuance of questionable tax bills; the establishment of independent oversight mechanisms for taxpayer protection and the review of interpretive letters; and comprehensive human rights education for tax and judicial officials to ensure compliance with the Two Covenants.”

Then comes the line that sums up the entire saga: “The Tai Ji Men case is a persistent issue that continues to affect the island’s human rights situation, refusing to fade because the underlying injustices remain unaddressed.”

It is a persistent issue indeed. One that has now appeared before the Human Rights Council in 2010, and again in 2021, 2022, 2023, 2024, 2025, and now 2026. This shadow is cast not by a lack of democracy but by the slow, relentless force of administrative inertia.

CAP-LC’s final warning is that taxation must never become a means of discrimination, and the Two Covenants must be upheld “in all countries that have committed to them.” The fact that this case—rooted in a 1996 crackdown, a 2007 acquittal, and a 2020 land nationalization—continues to be seen in Geneva indicates that something is deeply wrong.

It’s not just that CAP-LC has submitted another statement, but that the Tai Ji Men case has become a recurring issue in international human rights records. This case refuses to die because the injustice that created it remains unresolved.

When a tax bill turns into a human rights issue, and when a spiritual community’s land symbolizes administrative overreach, the world takes notice. And when the world notices twelve times, the matter is no longer local. It has become a global issue.

The Tai Ji Men case has reached the UN—again. And until justice is served, it seems determined to keep coming back.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.