A 24-year-old student was insulted for months on social media and committed suicide. The Two Sessions’ answer: more surveillance.

by Zhou Kexin

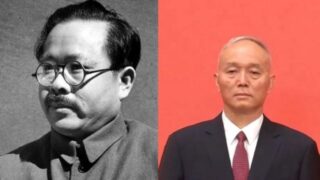

Zhou Qiang is one of the most powerful politicians in China. Once the national secretary of the Chinese Communist Youth League, he ascended to his current position of Chief Justice and President of the Supreme Court of China. Zheng Linghua was a young woman from Hangzhou, Zhejiang, who committed suicide on January 23 this year, after she had been insulted for months on social media for having dyed her hair pink. What do the two of them have in common?

Nothing, it would seem, yet that their paths had crossed became apparent at the recent Two Sessions, when Zhou delivered his report to the National People’s Congress on March 7. Zheng was one among many victims of cyberbullying in China (and around the world), yet her case created a special interest and soul-searching among netizens. Zhou used her case to promise a tougher control of social media to prevent cyberbullying—and criticism of the CCP.

Zheng was 24 when she died. She wanted to become a piano teacher, and when she was accepted as a music student at East China Normal University she believed her dream was about to come true. To celebrate, she dyed her hair pink. She posted images of herself on social media, including of a visit to her grandfather, who was then hospitalized and who had raised her after her mother died when she was six months old.

Pink hair is not that uncommon but for whatever reason thousands of netizens decided to attack Zheng with comments that the color made her look like a prostitute. Some noted that a woman with this hair color was obviously promiscuous and immoral, and should never be allowed to become a piano teacher. Others went so far as to suggest that she probably had sexual relationships with her grandfather, or the man who claimed to be her grandfather, as she was smiling at him “seductively” in the pictures. This was too much for the girl, who at first tried to fight back but in the end took her life.

The Supreme Court’s President used Zheng’s tragedy to claim that Xi Jinping is right: Internet, and social media in particular, are “chaotic,” and not regulated enough. Internet has become a “lawless space,” Zhou said. The Party should extend his control there, and Zhou vowed to impose severe punishments on those who bully others or “spread false information” or “inappropriate” comments.

Fighting cyberbullying, an international problem, is a worthy goal. But the same scheme always repeat itself in China. Every incident that leads netizens to criticize the Party is dealt with by claiming that the problem is that there is not enough control and surveillance, so more should be imposed. And the control will not target only, perhaps not even mostly, those who bully girls such as poor, pink-haired Zheng.

The repression, as Zhou said, will hit those who “spread false information,” meaning information not approved by the CCP, or post “inappropriate” comments, including those critical of the Party. From the point of view of the regime, Zheng did not die in vain. Even her death is being manipulated to impose and justify more repression.