“Psychobiographies and Godly Vision” argues that Paul the Apostle, Muhammad, and most founders of religions were no less mentally disturbed than “cult” leaders.

by Massimo Introvigne

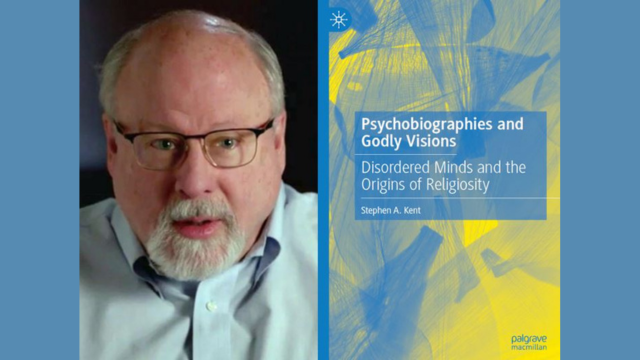

If you were hoping for nuance, subtlety, or even a flicker of intellectual generosity in Stephen Kent’s latest book, “Psychobiographies and Godly Visions: Disordered Minds and the Origins of Religiosity” (Palgrave Macmillan, 2025), you’re in for a disappointment as stark as a fluorescent light in a monastery. Kent, long known for his crusade against so-called “cults,” has finally dropped the pretense: it’s not just some fringe movements he’s after—it’s religion itself. All of it. From the desert prophets to Catholic saints, Kent’s verdict is in: hallucinations, the lot of them.

He does include a late disclaimer on the last page of the book: “I am not saying that all religions are founded by mentally disordered minds, but I do say that a good number of them are.” However, he references numerous religions but fails to provide a single example of one that was “not” founded by mentally ill individuals.

Kent—longtime sociologist and self-styled scourge of “cults”—finally sheds the last layer of academic restraint and delivers a sweeping dismissal not just of fringe spiritual movements, but of religion. Kent’s critics have long accused him of using anti-cultism as a tool to promote a broader hostility toward religion, and this book reads like a spectacular confirmation. All religious leaders are painted with the same brush: deluded, dangerous, and diagnostically compromised. This worldview is so totalizing that it leaves no room for metaphor, mystery, or the possibility that spiritual experience might be more than just neurological noise.

The book reads like a manifesto penned by a man who’s spent too long in the echo chamber of his own skepticism. Revelations? Hallucinations. Visions? Psychotic episodes. Spiritual experiences? Neural misfires. Kent doesn’t analyze religious phenomena as much as bulldoze them with the subtlety of a wrecking ball in a stained-glass factory.

His tone is clinical, but the subtext is unmistakable: believers are dupes, mystics are mad, and the sacred is just the brain misbehaving. It’s a worldview so reductive that it makes Freud look like a theologian. One might admire the audacity—if only it weren’t so intellectually claustrophobic.

Kent’s thesis is as stark as it is unyielding. Religious experience, he argues, is not a window into the transcendent but a symptom of cognitive malfunction. He places Joseph Smith’s foundational visions for Mormonism and Ellen G. White’s Adventist beginnings alongside Charles Manson’s apocalyptic ramblings, suggesting that all stem from similar psychological distortions. The comparison is not subtle—and that’s the point. Kent isn’t interested in theological nuance or historical context. He’s here to flatten the sacred into the clinical.

It’s no surprise that, in his diagnostic zeal, Kent labels Reverend Moon and L. Ron Hubbard as “malignant narcissists”—he’s spent much of his career engaged in such clinical name-calling. But this time, the net is cast wider. Joseph Smith, founder of the Latter-Day Saints, is said to suffer from a “personality disorder associated with deceitfulness, inflation of their own achievements, and using others for their own end.” John Wesley and Billy Graham, among others, are explained away as products of “battered child syndrome,” their teachings allegedly shaped by early corporal punishment. Ellen G. White, the prophetic voice behind Seventh-day Adventism, is reduced to a textbook case of “histrionic personality disorder.” Even the Biblical prophet Ezekiel is not spared: he “suffered from forms of schizophrenia or the closely related condition (schizo-affective disorder),” unless it was “epilepsy.”

The longest and most elaborate diagnoses are reserved for Paul the Apostle and Muhammad. Paul, Kent insists, “suffered from epilepsy,” evidenced by his vision of “a great light from heaven” (Acts 22:6), which Kent interprets as an “epileptic aura.” Jesus’ voice that Paul and other apostles claimed to hear after his death was, for Kent, “suggestive of another common aspect of seizures—auditory auras or auditory hallucinations.” Paul’s prolific letter-writing is chalked up to “hypergraphia,” a symptom “well known to epilepsy researchers.” Yet Kent’s argument stumbles: many of the epistles attributed to Paul are widely believed by Biblical scholars to have been written by others, and modern academics—including Kent himself—have written far more than Paul ever did. Should they, too, be diagnosed?

Kent’s historical imagination is vivid. He laments that early Christians failed to recognize Paul’s epilepsy, a failure he sees as historically catastrophic. “If the early Christians in Galatia had followed the culturally normative reaction to an epileptic having a seizure and spit on or near Paul, then Christianity would not have developed as it did and may not even have survived its first few generations.” One is left to wonder what Kent might have advised the Galatians, had he been available.

Kent’s psychiatric lens extends to sexuality. Paul’s advocacy of chastity is interpreted as evidence of being “hyposexual,” which Kent claims “would be in line with someone who had epilepsy.” Meanwhile, Muhammad’s revelations are also linked to epilepsy, though Kent notes his multiple marriages. No contradiction here for Kent’s pop psychiatry: “Paul had hyposexuality and Muhammad had hypersexuality, which connects their sexual dysfunction with the affliction that the two of them most assuredly had.”

Kent’s conclusion about Paul and Muhammad is sweeping. “The medical and neurological evidence seems indisputable that their hallucinations were epileptic, and their historical contexts were of importance only because they provided them and their communities options for interpreting them. Other than providing those options, their cultural contexts were of minor consequence, since both religious figures lived in times before scientific interpretations (not to mention treatments) were available.” Based on such diagnoses, had Paul and Muhammad lived today, their communities would have been raided, their leaders institutionalized, and their followers subjected to deprogramming.

A chapter on Jesus might be anticipated as well. Following similar reasoning, his claims of walking on water and raising the dead could be seen as psychotic delusions. Yet, Kent wisely chooses to ignore Jesus. He’s not alone in this. As an Italian, I recall the epitaph on the grave of the well-known 16th-century anti-religious poet Pietro Aretino: “Di tutti disse mal fuorché di Cristo / scusandosi col dir ‘Non lo conosco,’” which translates to “He badmouthed everyone except Christ / and apologized by saying ‘I don’t know him.’”

The scope of Kent’s vituperation is staggering. “Simply looking at the current estimated populations of Christianity and Islam, over four billion people claim affiliations with those faiths, and nearly fifteen million more identifying with Judaism. If we add to those numbers people belonging to [other] traditions founded or built by figures with mental health issues, then the influence of religious figures with disorders becomes even more startling.” And it doesn’t stop there. “There is clinical reason to assume that people who believe that they are having extraterrestrial contact may be demonstrating a symptom of schizophrenia.” Nor are ordinary believers spared: “people who maintain that non-material spirits and forces do exist” and “offer prayers for divine intercession” are said to harbor “magical” beliefs and may unknowingly suffer from “mental disorders.” The cure, it seems, would require a program of unprecedented scope.

The effect is cumulative and corrosive: by the end, the reader is left with the impression that religion is little more than a global outbreak of untreated mental illness. “Perhaps God exists,” Kent cynically concludes, “but if He (or She or It or They) do, then one wonders why God chose so many revelations to come through disordered minds.”

What’s striking is not just Kent’s skepticism, but his apparent delight in dismantling centuries of spiritual tradition. There’s a performative edge to his prose, a kind of academic swagger that borders on contempt. He doesn’t merely question the veracity of religious experience—he ridicules it. It’s the kind of rhetoric that would make even Richard Dawkins wince.

In passing, Kent rehashes his long-standing grievance against scholars of new religious movements, whom he accuses of forming a protective lobby that stifles academic discussion of brainwashing. His familiar refrain, largely ignored by these scholars over the decades, hardly demands renewed attention here.

And yet, for all its bravado, the book feels oddly dated. The idea that religious visions are reducible to brain chemistry is hardly new—it’s been circulating since the Enlightenment, and neuroscientists have been poking at it for decades. Kent’s contribution is less original insight than polemical fervor. He’s not advancing the conversation; he’s ending it with a gavel strike.

There is, however, a silver lining to Kent’s aggressiveness. Future lawyers facing him as an expert witness in cases against so-called “cults” may find unexpected ammunition in this book. They could reasonably argue that Kent’s antipathy toward the supernatural is so sweeping and unrelenting that it undermines his credibility as a neutral observer. His standards of culpability are so severe, one suspects he’d have had no qualms about indicting Muhammad or Saint Paul had they crossed his courtroom threshold. In this sense, the book offers not just a critique of religious leaders—it inadvertently becomes a liability for its author.

There’s a certain irony in Kent’s approach. In his zeal to expose the irrationality of belief, he adopts a kind of dogmatism himself—one that’s every bit as rigid and unyielding as the fundamentalism he critiques. The result is a book that’s less a work of scholarship than a manifesto of disenchantment. It doesn’t invite dialogue; it shuts it down.

For readers who already see religion as a dangerous delusion, Kent’s book will feel like vindication. For everyone else—believers, seekers, or simply those curious about the complexities of faith—it’s a joyless, monochrome portrait of human spirituality. And for a subject as rich and multifaceted as religion, that’s not just reductive. It’s dangerous.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.