A graphic novel, available in Italian and English, illustrates how comics can effectively communicate profound religious narratives.

by Massimo Introvigne

Saint Agatha of Sicily is one of the most revered Christian martyrs. She is celebrated for her unwavering faith and profound suffering. Her story, filled with devotion and resilience, has consistently inspired artists over the centuries. From Byzantine mosaics to Baroque masterpieces, her image has been depicted in various styles, emphasizing martyrdom and divine grace.

One of the earliest depictions of Saint Agatha can be found in the Byzantine mosaics (6th–7th century CE) at the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna. In these artworks, she appears as a noblewoman adorned with a veil and jewelry, illustrating the Byzantine artistic style.

During the Renaissance and Baroque eras, artists began to portray Saint Agatha with greater realism and emotional depth. Notable depictions of the Saint include Francisco de Zurbarán’s (1598–1664) “Saint Agatha,” a Spanish Baroque masterpiece that highlights her calm yet mournful expression and spiritual resilience.

The more dramatic “Martyrdom of Saint Agatha” by Sebastiano del Piombo (1485–1547) powerfully represents her suffering and the cruelty of her oppressors.

Some contemporary artists have provided unique artistic viewpoints of Saint Agatha. One notable figure is Brother Arturo Olivas, OFS (1958–2017), who crafted Catholic imagery influenced by the style of 18th and 19th-century New Mexican religious folk artists.

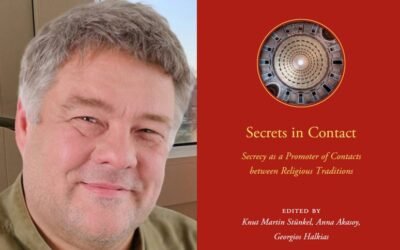

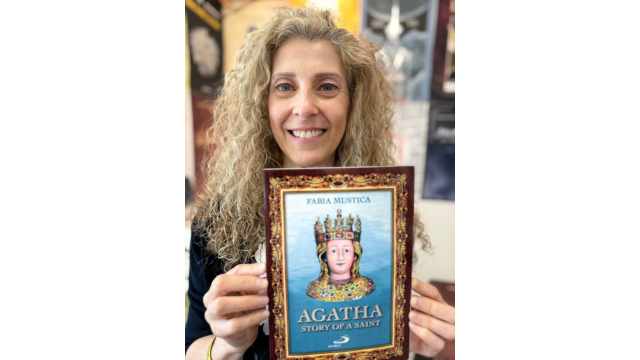

Now, it’s the comics. Fabia Mustica is a comic artist from Catania who published “Agatha: Story of a Saint” in Italian and English with Edizioni San Paolo, the most prominent Italian Catholic publisher. I met her at this month’s Etnacomics, the Catania comic convention, and Italy’s third-largest.

Mustica recounts a promise made to Agatha years ago, following the moment her cherished cousin awoke from a deep coma caused by a car accident. This event coincided with the night the hospital chaplain circulated the Veil of Saint Agatha in the intensive care unit. This relic, treasured by the residents of Catania, is believed to be the same veil that endured while her tormentor, Quintianus, forced Agatha to walk over scorching coals and burn.

Mustica vowed to dedicate a graphic novel to the saint. However, distracted by her busy life, she delayed fulfilling this promise until the saint reminded her during her prayer before her statue in Catania Cathedral.

Mustica, an elegant comic artist, provides context about Roman Sicily and the 3rd-century persecution of Christians before recounting Agatha’s life.

The saint was born in Catania, Sicily, in the early 3rd century. Coming from a noble family, she was known for her beauty and devotion. As a dedicated Christian, she committed her life to God, rejecting all marriage proposals, including one from the Roman governor Quintianus. Enraged by her refusal, Quintianus took advantage of the prohibition against Christianity and imprisoned Agatha. He then offered her the choice of marrying him or facing execution.

After Agatha still refused the governor’s advances, he inflicted severe torture upon her. Nevertheless, Agatha remained steadfast in her convictions despite the pain she experienced.

Mustica recounts Agatha’s martyrdom in a traditional narrative. She illustrates the mutilation of Agatha’s breasts during her persecution, which becomes a potent symbol of her suffering and strength. Saint Agatha’s imagery prominently features breasts, reflecting the brutal torture she faced. In artistic representations, she is frequently depicted holding a platter with her severed breasts, symbolizing both her torment and her unwavering faith. This imagery connects to themes of nourishment, sacrifice, and purity. Some artists portray her suffering with vivid realism, whereas others present her image with a tranquil dignity, emphasizing her spiritual resilience over her physical pain.

When depicting Agatha’s martyrdom, there is a risk of falling into poor taste and Grand Guignol. Mustica skillfully avoids the dual temptations of sanitizing the brutality and focusing solely on the most morbid details, providing a believable representation of the traditional story.

Next, the comic artist illustrates Saint Peter’s visit to Agatha in prison, during which he miraculously healed her wounds. However, her pain persisted, and she was ultimately martyred by being placed on burning embers. Her death was marked by an earthquake in Catania, which leads many to view her as a protector against natural disasters, particularly the eruptions of Mount Etna.

The graphic novel concludes with the citizens of Catania in outrage against Quintianus for the murder of an innocent girl. As he attempts to flee the city, he is killed by his horse. Meanwhile, Agatha is celebrated by the Christians of Catania and mysterious angelic figures who appear at her burial.

Mustica engages with centuries of rich and deeply symbolic iconography related to Saint Agatha. The comic artist, however, aims to tell a story rather than create an icon. The graphic novel does mention the miraculous, yet it remains grounded in realism. This is how the lives of the saints should preferably be depicted in comics. It is a lesson taught by one of the greatest comic artists in history, Jijé (Joseph Gillain, 1914–1980), in his 1943 life of Saint John Bosco—and one that Mustica has not overlooked.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.