Boarding schools for sons and daughters of the Doukhobors were a brutal attempt at eradicating their culture and identity. Canada has yet to apologize.

by Susan J. Palmer

Article 3 of 3. Read article 1 and article 2.

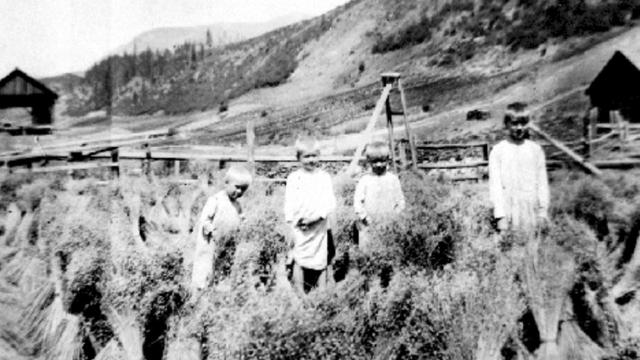

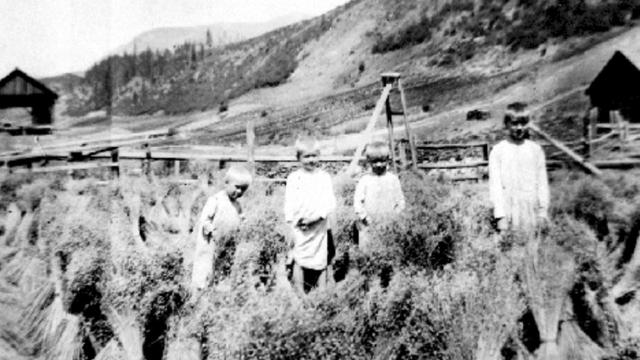

Doukhobors were already regarded as a problem before the 1950s. But in 1952, the Social Credit Party came to power under W.A.C. Bennett, who adopted a “tough on Douks” policy. Between 1953 and 1955, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, were sent out on an operation dubbed “Operation Snatch” to conduct a series of raids on the Sons of Freedom homes in or near Krestova. They apprehended around 200 children, supposedly of school age (7–14). However, since Freedomite parents refused to register births, many children as young as 4 and 5 were seized. These children were forcibly captured, loaded on buses, and driven 99 kms north to a former tuberculosis sanatorium in the village of New Denver.

Ashleigh B. Androsoff Arnosoff vividly describes the school’s conditions in her 1999 Masters thesis: “These children left a warm, Russian-speaking family-centered communal environment to arrive in a cold, disorganized, badly equipped English–speaking institution. The matrons and teachers were overworked and meting out punishments. The parents were permitted to visit only every second Sunday: a privilege taken away if a child was deemed to misbehave. Parents often drove over one hundred miles to see their children in vain, for their visit had been cancelled without informing them, due to the child’s deemed ‘misbehaviour.’ Parents and children Sunday meetings were divided by a tall chain link fence. Parents kissed their children through metal links, passing picnic baskets and blankets… over the fence.”

When our McGill team interviewed the Doukhobors in 2019, we heard many stories about the RCMP raids in the 1950s. One lady recalled how, as a little girl, she was bundled up every morning and sent out to hide on the wooded mountain all winter long to avoid police raids, not returning home until she saw smoke from the chimney, then she could run home for hot soup and bread with her parents. One evening she was running down the mountain towards home when she suddenly saw police cars drawing up in the drive. She turned back to flee and found a huge bear in her path standing on his haunches, staring right at her. She glanced back at the police cars, then looked in the bear’s eyes. “I could see he meant me no harm.” So, she walked slowly around him to go hide in the woods. The bear turned his head curiously. Other Doukhobors described childhood experiences of hiding in secret compartments, under the beds, beneath the house, in the outhouse when the RCMP came hunting for them. One described how she hid in a secret closet built by her father, and when a Mounty tapped on it, she suddenly peed her pants. The Mounty saw urine leaking across the floor but, being a kind man, he called out to his fellows, “Nobody here!” and the RCMP left.

One man in his seventies spoke of a certain matron at the New Denver dormitories who used to corner little Doukhobor boys in closets and sexually molest them until they cried or screamed. He choked up as he described how she had threatened him not to tell. There were stories about trying to kiss their parents through the icy wire fence, and about how the matrons chopped off the girls’ beautiful golden braids. There were more pleasant stories about how they played with the children of the 22,000 Japanese Canadians whose parents had been forcibly uprooted, dispossessed, and incarcerated in New Denver during World War II.

Perhaps the worst story was about a certain teacher who made no effort to teach subjects, but simple read from the Hardy Boys books and instructed her pupils to bring her candies. She would giggle and give them points. Thus, the children learned English and sports, but were behind in their education when they “graduated” from the New Denver school. Most of them found work in as farmers, lumberjacks, truck drivers, waitresses, gas station attendants, just as they would have if Operation Snatch had never happened. Only a few educated themselves and went on to university.

The notorious New Denver residence lasted from 1953 to 1959, until the last of the Freedomite parents finally signed a contract with the government promising to send their children to public school. Thus, the Sons of Freedom were finally broken, tamed, assimilated—or were they?

In 2001, the last reported arsonist from the Sons of Freedom, an 81-year-old woman named Mary Braun, received a 6-year sentence for setting fire to a community college building, causing $350,000 in damages. She immediately disrobed in court. This was her fifteenth conviction for arson.

How are these children of the Freedomites today? Around 100 of them (now in their 70s), have regrouped as The New Denver Survivors Collective (NDSC). They have been lobbying for an apology from the B.C. government since 2000.

In 1999 a B.C. Ombudsman’s report came out, stating that the Sons of Freedom children were “wrongfully removed from their families,” and “wrongfully confined to a prison-like school.”

This galvanized the NDSC to file a lawsuit against the B.C. government, alleging negligence, unlawful confinement and forcibly removal from their homes.

They also demanded an apology.

But their apology was not forthcoming, instead, B.C. Attorney General, Geoff Plant, issued a “Statement of Regret.”

In February 2012, one hundred members of the New Denver Survivors Collective stood before the B.C. Human Rights Tribunal to argue that the government had unjustly refused to apologize. They stated that they had been the child victims of a long-standing cultural battle between their community and the province. They compared themselves to the thousands of Indian Residential School survivors who, as children, also experienced psychological, physical, and sexual abuse, and were punished for speaking their own language.

This was a valid comparison, for the forcible separation of children from parents is a familiar strategy of governments seeking to undermine and assimilate their minority cultures. We have seen the Australian governments’ policies in the 1900s regarding Aborigine “stolen generation” children; also, in Canada’s 160 years of residential schools for children of the First Nations and Metis people; and more recently, in China’s “Happy Heart” boarding schools for Uyghur children. All these children, whether Aboriginal, Indigenous, or Uyghur share a common experience. They were forcibly taken from their homes and confined to crowded “residential” schools, with little or no contact with parents. Their hair was shorn for a uniform bald or “pudding bowl” institutional look. Forbidden to speak their mother tongue or to seek solace in native spiritual practices, they were severely disciplined and indoctrinated into the nationalistic values and worldviews of the ruling majority.

But there is an impressive history of government apologies.

The Canadian government, after establishing the Truth and Reconciliation investigation in 2014, formally acknowledged its fault regarding its past treatment of Indigenous peoples. On June 25, 2021, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau apologized for the “incredibly harmful” government policies after almost 1,000 unmarked mass graves of indigenous children were discovered at the sites of residential schools in B.C. and Saskatchewan.

On February 13, 2008, Australia’s PM, Kevin Rudd unexpectedly apologized to the Aboriginal peoples whose lives were blighted by past government policies of forced child removal and assimilation.

But China has yet to acknowledge its treatment of the Uyghurs of Xinjiang province, deemed as a “genocide” by eight counties, let alone to apologize for its “Happy Heart” boarding schools.

The children of New Denver are also still awaiting their apology.

This paper was initially written for and presented at the War and Peace conference at l’Université Bordeaux Montaigne in Bordeaux, France, organized by Professor Bernadette Rigal-Cellard.