August 14 was the 160th anniversary of the birth of the famous anarchist, who lived his political beliefs as if they were a religion.

by Massimo Introvigne

On August 14, I found myself in Rosignano Marittimo, a quiet Tuscan town with a rebellious heart, attending the 160th anniversary celebration of Pietro Gori’s birth. It included a concert and a guided visit to the “Fondo Pietro Gori,” a collection hosted by the local archeological museum.

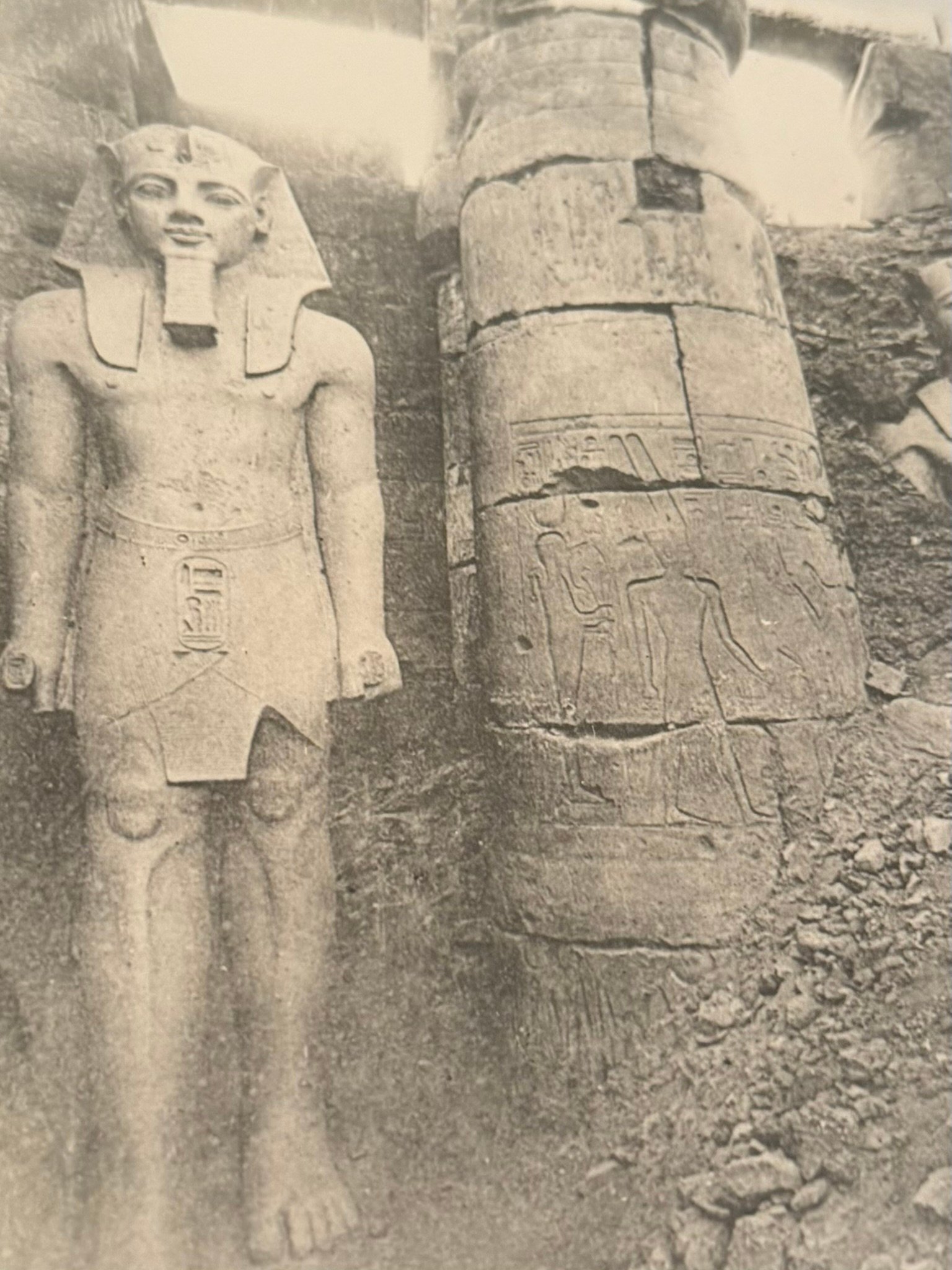

Gori (1865–1911) was Italy’s most iconic anarchist poet, lawyer, and agitator—a man whose verses stirred exiles and whose speeches unsettled regimes. Rosignano, neighbor to my own Castellina Marittima, is where his mother was from, Gori rests, and the “Fondo” preserves his desk, library, photographs, some letters, and a few relics of his globe-trotting life—including, curiously, a crocodile that may have come from South America, unless it was Egypt.

The Fondo opened its doors for the occasion. I joined a guided tour that traced Gori’s travels to the U.S., Palestine, Egypt, and Argentina, where he explored Patagonia with painter Angiolo Tommasi (1858–1923), a fellow Tuscan active in the Macchiaioli movement.

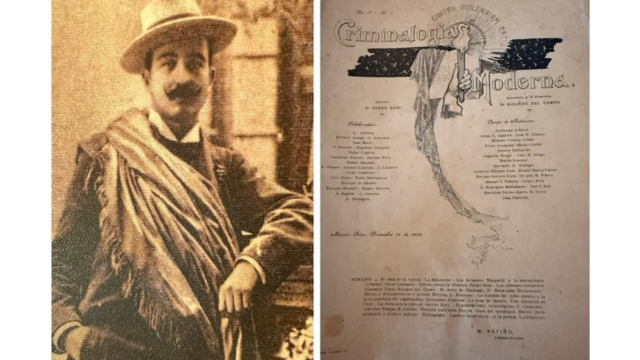

In Argentina, Gori co-founded “Criminologia Moderna,” a journal that attracted serious academic minds. His influence on the South American country was profound, yet barely remembered today.

But Gori was more than a cosmopolitan intellectual. He was a man possessed—by an idea. He never married, never pursued romantic entanglements, declaring in his song “Amore ribelle” that he was married to anarchy. Leda Rafanelli (1880–1971), his friend and fellow anarchist (who later converted to her own brand of Islam), recounted a delicious anecdote: Gori’s sister tried to set him up with a wealthy American heiress. The woman was smitten, but Gori, unimpressed, opted instead for a radical haircut—half-shaved, half-wild, and repellent to any woman—and wrote “Amore ribelle” as a declaration of fidelity to his cause. “All’amor tuo preferisco l’idea,” he sang. “To your love, I prefer the idea.” It wasn’t just a lyric—it was a vow.

Gori’s fervor wasn’t limited to poetic defiance. He was a militant anti-clericalist, and his activism often targeted the Catholic Church. In 1909, when Spanish anarchist educator Francisco Ferrer Guardia (1859–1909) was executed—falsely accused of inciting violent rebellion and reportedly at the instigation of the Catholic Church (he was a vitriolic anticlerical)—Gori joined the wave of anti-Catholic protests that swept Italy. These demonstrations weren’t just political; they were liturgical in their own way, complete with hymns, martyrs, and sacred texts.

With their rituals, songs, and uncompromising devotion, Gori and his comrades can be studied through the lens of religious movements. Their “faith” was anarchism, their “church” the barricade, and their saints were those who died resisting oppression. In this sense, Tuscan anarchism wasn’t just a political ideology—it was a spiritual rebellion.

And so, as I stood in the museum beside Gori’s desk and his crocodile, I couldn’t help but reflect on the paradox: a man who rejected religion, yet inspired a movement with all the trappings of one. A man who scorned romantic love, yet wrote verses that seduced generations. A man who died as a rebel, but whose memory is now officially celebrated, including in the very town he once had to flee, pursued by the police. Pietro Gori didn’t just live anarchism—he embodied it. And in Rosignano, on his 160th birthday, his religiously irreligious faith resonated once more.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.