Religious liberty is a key test to assess the democratic nature of a government. It remained a difficult test for Taiwan even after the end of the Martial Law.

by Tsai Cheng-An

Article 5 of 7.

Read article 1, article 2, article 3, and article 4.

What happened in 1996 was a clear violation of democratic principles and freedom of religion or belief (FoRB), as religious and spiritual movements were targeted for political reasons. Even after 1996, the political party in power still mobilized many media, judicial organs, and national tax authorities with their powerful overall power putting together party and government, judicial system and tax administration.

“Religion” is usually associated with one or more specific beliefs and worship systems, either theistic or non-theistic. However, in human rights law, “religious freedom” also includes the right to support unconventional beliefs and non-religious beliefs, such as atheism or agnosticism. In 1993, General Comment no. 22 by the United Nations Human Rights Committee, interpreting article 18 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, explained that “article 18 protects theistic, non-theistic and atheistic beliefs, as well as the right not to profess any religion or belief. The terms ‘belief’ and ‘religion’ are to be broadly construed.”

Beliefs about religion offer hope and comfort to billions around the world and have an enormous potential for peace and reconciliation. However, they may also be a source of great tension and conflict. This complexity, and the difficulty of an inclusive definition of “religion” and “belief,” are reflected in the ongoing struggle to protect freedom of religion or belief in the context of international human rights.

The United Nations recognized the importance of freedom of religion or belief in article 18 of its 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Similar provisions followed in other well-known United Nations documents.

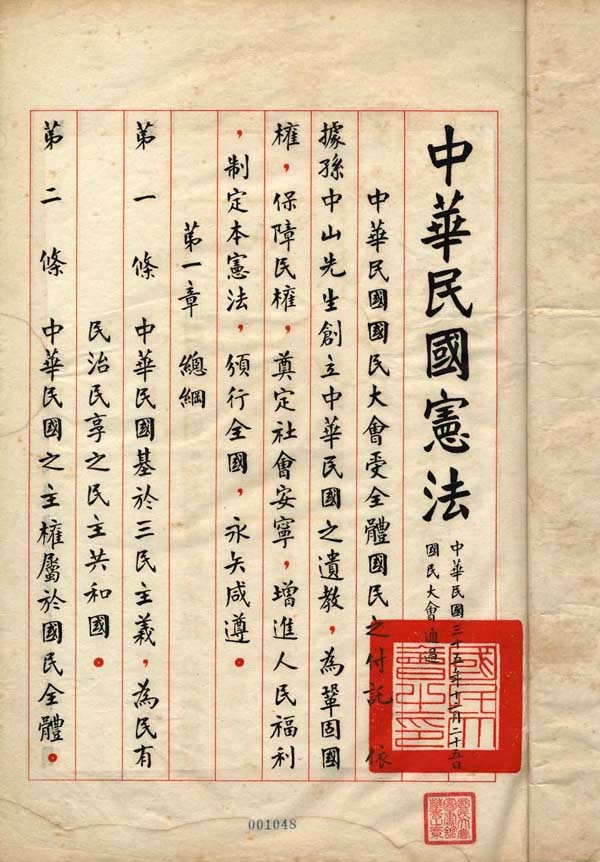

The Constitution of the Republic of China (Taiwan) also includes the principle of freedom of religion in article 7 (“The people of the Republic of China are equal in law, regardless of gender, religion, race, class, or political party”) and article 13 (“The people shall have freedom of religious belief”). According to Judicial Interpretation no. 573, “The state shall observe the principle of neutrality and tolerance towards religion.” Interpretation no. 490 has a similar statement about freedom of religion: “its scope of protection includes the freedom of inner belief, the freedom of religious conduct, and the freedom of religious association.” Accordingly, Taiwan’s Constitution does guarantee the citizen’s freedom of religion or belief (FoRB). But in fact, do people in Taiwan really enjoy FoRB?

According to a study conducted by the Hudson Institute’s Center for Religious Liberty, FoRB in various countries is statistically correlated with the existence of fundamental human rights and the success of democracy. The Pew Research Center noted in 2012 that data collected between 2007 and 2012 showed that religious minorities were still the target of government restrictions and hostile acts in 61% of the countries around the world. FoRB and democracy are so inextricably linked that democracy can only last where FoRB is guaranteed. Thus, it is important to understand the relationship between the development of democracy in Taiwan and FoRB.

Under the Martial Law regime, i.e., before 1987, the authoritarian government in Taiwan did not fully guarantee FoRB. The Martial Law allowed “restricting or prohibiting religious activities that interfere with public security,” established the authoritarian government’s control over religion, and offered a legal justification for multiple FoRB violations, despite the wording of Taiwan’s Constitution.

Although the Kuomintang (KMT) government claimed to give all religions freedom to develop, this was conditional. If religious groups agreed with the government, or were not suspected of not supporting it, most of them could enjoy religious freedom. However, if religious groups had different political views from the government, or if the KMT party felt it was not supported by certain groups, repression followed. We have seen how Yiguandao and the New Testament Church were persecuted, but others such as Soka Gakkai, the Unification Church, the True Jesus Church, the Jehovah’s Witnesses, and the Presbyterian Church also saw their activities limited by the KMT governments, as documented by Canadian scholar André Laliberté.

At the end of the Martial Law period, the KMT and government institutions gradually began to adopt relatively relaxed policies. At the same time, some oppressed religious groups became important forces that promoted the lifting of the Martial Law.

During the post-authoritarian period from 1988 to 2016, the relationship between political and religious conflicts gradually changed. Many social groups, and experts and scholars, demanded that the ruling government should not persecute religious groups without legal basis, and insisted that human rights should no longer be violated for political reasons as it had happened under the non-democratic authoritarian system. However, in the early stage of the post-authoritarian system, the protection of human rights was not a core value of the governance. The purge culture of the authoritarian system was still prevalent. The political purge and crackdown on religious movements after the 1996 presidential elections tried to eradicate several religious groups, showing that contradictions still existed.

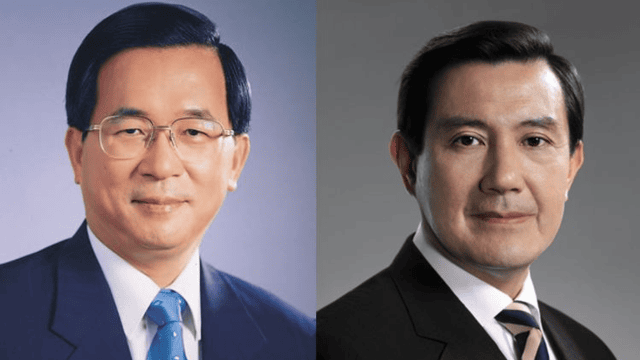

A case in point was the relationship between the government and the Presbyterian Church, which criticized the authoritarian rule and several aspects of the KMT’s cross-Strait policies. Even in the year 2000, when the first non-KMT president, Chen Shui-Bian (b. 1950), was elected, the Presbyterian Church in Taiwan was still anxious about both the governmental approach to religion and cross-Strait policies. When in 2008 the KMT recaptured the presidency with Ma Ying-Jeou, this anxiety became more intense as the Presbyterian Church, like others, perceived Ma as favorable to a reunification with Mainland China.

Why was Taiwan’s implementation of FORB delayed? Italian scholar Massimo Introvigne compared Taiwan to South Korea, noting that the two countries were born under the threat of China and North Korea respectively, which explains why they were ruled by authoritarian regimes for many years and their democratic allies did not object. Due to this external threat, it was more difficult for Taiwan and South Korea to walk towards democracy than it was, for example, for Italy after Fascism. In Taiwan and South Korea, the transition from the autocratic regime to a democratic system was realized gradually. During the transition period, the old habits, ideas, and behaviors of the old bureaucrats still remained. One of the great tests for the new democracies was to accommodate religious minorities. Both South Korea and Taiwan restricted the activities of religious and spiritual movements during their transition to democracy, with consequences still at work today, as evidenced by the Tai Ji Men case.

Tsai Cheng-An received his Ph.D. in Technology Management from National Chengchi University and his MS in Industrial Engineering from National Tsinghua University in Taiwan. He teaches innovation management, business model analysis, and new business development strategies at Shih Chien University, Taipei, Taiwan. Prior to his academic career, he had 18 years of practical experience in the industry, and his research interests are in decision making, business model innovation, and corporate entrepreneurship, as well as in the area of transitional justice and freedom of religion or belief. He has published in the International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviors & Research (SSCI), Technology Analysis and Strategic Management (SSCI), Logistics (SCIE), Management Review (TSSCI), Journal of Management (TSSCI), Sun Yat-sen Management Review (TSSCI), Journal of Science and Technology Management (TSSCI) and Forum for Industry and Management (TSSCI).