After Blavatsky’s death, the artist joined Katherine Tingley’s Theosophical community in California and became one of its most prominent members.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 2 of 3 (published on consecutive Saturdays). Read article 1.

While Machell, after Blavatsky’s death, continued to produce works inspired by Theosophy, a controversy developed within the Theosophical Society, eventually impacting Machell’s life and career. William Quan Judge was one of the original companions of Madame Blavatsky and the leader of the powerful American branch of the Theosophical Society. After Blavatsky’s death, Judge claimed to receive messages from the same Masters with whom Blavatsky had been in contact. These messages were not accepted by Colonel Henry Steel Olcott (1832–1907), who succeeded Blavatsky as president of the Theosophical Society, nor by his closest associate and successor, Annie Besant (1847–1933). In 1895, Judge separated from the Theosophical Society, carrying most American members into the schismatic Theosophical Society in America. This faction had British followers, too, and London Machell’s studio at Earl’s Court was a center of strong support for Judge.

In 1896, Judge died and was succeeded by Katherine Tingley. However, some 200 members later disputed her succession and formed a branch in New York, led by Judge’s secretary Ernest Temple Hargrove (1870–1939), which continued a separate existence until 1943. In 1896, as part of her so-called World Crusade, Tingley came to Britain to gather European followers for her faction and organize a Theosophical Society in Europe loyal to the Judge-Tingley line of succession. A convention was organized in Dublin in August 1896. As he later reported, Machell’s “recognition of Katherine Tingley was as instantaneous and as thorough as [his] recognition of H. P. Blavatsky had been.” He attended the Dublin convention and followed Tingley and her closest followers when they journeyed to Killarney, Ireland. There, following Tingley’s clairvoyant lead, they eventually found the cornerstone they would use for a projected School for the Revival of the Lost Mysteries of Antiquity to be established in the U.S. Together with Machell, one participant in that fateful journey was the poet George William Russell (1867–1935), who wrote under the pseudonym of ‘AE,’ and later wrote about these “American Crusaders at Killarney.”

After the memorable journey to Ireland, Machell’s studio at Earl’s Court became a center of the Tingley faction in London. When Tingley took possession of the old London Headquarters of the Theosophical Society, at 19 Avenue Road, Machell opened a second studio there. For Machell, “the teaching of Madame Blavatsky has been made practical by Katherine Tingley. And Theosophy has been shown to be just what its name implies: Divine Wisdom, and just what Madame Blavatsky said it was, not merely a religion, but Religion itself.”

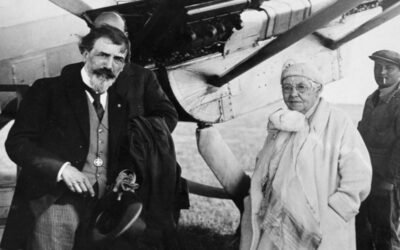

In 1897, Tingley started the ambitious project of a Theosophical “city” called Lomaland in Point Loma, near San Diego, California, which should include inter alia a school, a university, a theatre, agricultural facilities, factories, and a hotel. With her clairvoyant powers, Tingley had seen Point Loma as where the Killarney cornerstone should be laid and become the foundation of the School for the Revival of the Lost Mysteries of Antiquity. In 1900, Tingley moved the headquarters of the Theosophical Society in America, now renamed the Universal Brotherhood and Theosophical Society, to Lomaland.

The new name indicated the intention of establishing a truly international society instead of an American one. Tingley tried to attract to Lomaland members from all over the world, targeting particularly artists, since Lomaland in her project should include a Theosophical Art School. Machell was an obvious choice in England, and Tingley also recruited a lesser Theosophist painter who had exhibited at the Royal Academy, Charles James Ryan (1865–1949). Both men arrived in Point Loma on December 28, 1900. Machell brought with him his son Montague (1888–1975), leaving in England his wife and the elder son Henry Reginald, who would eventually move to New Zealand, enlist in the Auckland Regiment, and die in World War I in France on September 29, 1918. The younger son, Montague, would become a gifted musician and a loyal follower of Tingley before leaving Point Loma in 1930 to join the Phoenix Symphony Orchestra.

Tingley wanted most of all from Machell to set up a school of art as part of her Râja Yoga Academy. According to historian Bruce Kamerling, “art instruction at the Râja Yoga Academy was in the conservative academic tradition common at that time. Students began by producing charcoal drawings after plaster casts of architectural details or fragments of antique sculpture. They were also taught to look at an object and then sketch it from memory. Sculptural modeling was also integral to art training, and more advanced students could learn to work in oil, pastel, and watercolor. Landscape classes would meet at some scenic spot on the Lomaland property and begin work.”

Painting landscapes was at the center of the classes. Although this was not Machell’s specialty, he and Tingley could recruit two gifted teachers, long-time Theosophists Leonard Lester (1870–1952) and Hungarian-born Maurice Braun (1877–1941). The latter never became a resident of Lomaland but settled in San Diego to be close to the school. Tingley later helped Braun found the San Diego Academy of Art for non-Theosophist students in downtown San Diego, where Braun had among his students Alfred Richard Mitchell (1888–1972), who eventually became a well–known landscape painter.

In 1903, the faculty at the Lomaland school was joined by another Englishman, Joseph Fussel Sr. (1818–1912), a professor at the Art School of Nottingham whose son was a committed Theosophist and who, despite arriving in California at the age of 85, still taught for some years. Edith White (1855–1946), who specialized in painting roses, also became an essential teacher from 1902. In time, a real “colony” of artists emerged, whose idea of forming an artistic brotherhood led them to sign paintings with their names followed by the words “Point Loma Art School.”

“Soon after the arrival of Machell at Point Loma—reports Emmett A. Greenwalt (1907–1993) in his history of Lomaland—, it was observed that he possessed a remarkable skill in interior and exterior decoration, especially with wood surfaces,” including architectural ornamentation and carving screens, furniture, and frames for his paintings. A textbook on American craft comments that chairs, screens, and stools by Machell are “decorated with forms reminiscent of Art Nouveau, Celtic interlace, Gothic tracery, flames and wings. They are wonderfully inventive, completely unlike any other furniture made in America.” The same textbook mentions the throne Machell created for Tingley, where “the back and sides of the chair are carved into fantastic writhing shapes and the whole is painted in a cream color. In effect, the chair is a platform for a collection of carved panels, a virtuoso display of design and chisel–work. But it’s not a great example of sound construction: the joints are held together with pegs, which are notoriously prone to coming loose.” Greenwalt adds that Machell always “avoided literal duplication of nature or his work, for no two of his ritual chairs, flower stands, and desks are exactly alike.”

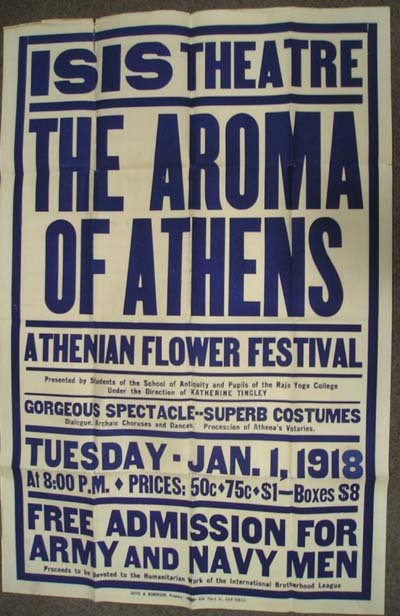

Unfortunately, some buildings were demolished after Lomaland’s demise in the aftermath of the world economic crisis of 1942. Almost nothing of Machell’s original decoration work and murals survives in the old Lomaland buildings preserved within the present-day campus of Point Loma Nazarene University, which include the original Greek Theatre, where the artist once played the Greek artist Phidias (ca. 480–430 B.C.) in Tingley’s play “The Aroma of Athens.” He also performed as Plato in “The Conquest of Death,” and Theon, father of Hypatia, in “The Wisdom of Hypatia,” both original Lomaland productions; as the ghost of Clytemnestra in “The Eumenides” of Aeschylus (ca. 525–456 B.C.), and various characters in plays by William Shakespeare (1564–1616). He also assisted Tingley in directing plays by Shakespeare, not only at Lomaland but also, in 1921, in Newburyport, Massachusetts, where Tingley organized an open–air theater, The Laurels, at her childhood home.

The Temple at Lomaland was destroyed by fire in 1952. Still, Machell’s two massive doors survive in the San Diego Historical Society archives at the Junipero Serra Museum in San Diego.

Evelyn A. Kirkley, who has studied gender issues at Lomaland, argues that the doors symbolize a quite conventional vision of maleness and femininity. However, the community was led by a woman. The figures on the doors represent “an ideal male and female, the apex of evolutionary development. In some ways, the figures are very similar. They are the same height and build. Their Indo–European facial features are virtually identical. Halos of natural vegetation rest above their heads. At the same time, there are distinct differences between them, representing ideal feminine and masculine qualities. The man is dressed in medieval armor, representing strength and aggressiveness. His horned helmet and sword suggest courage, not to mention sexual potency. A dog lies at his feet, symbolizing loyalty. The woman’s flowing robes suggest softness and sensuality; they hint at ancient Greek mysteries. She holds a key symbolizing knowledge. Lilies grow at her feet and a wreath of flowers encircles her brow, both representing purity.”

Machell’s idea was to represent Tristan and Isolde, but medieval chevaliers and dames perpetuated a vision of gender roles at odds with feminism. This is consistent with historian Penny B. Waterstone’s idea of Lomaland as a “Victorian middle class paradise based on the gendered virtues of (manly) self–control and (womanly) self-sacrifice,” where on the other hand “an ideology of woman’s morally superior nature” was used to “expand woman’s ‘natural’ sphere of influence.”

Machell was a regular and prolific contributor to Tingley’s “The Theosophical Path” and other Theosophical magazines. While most of his articles are general expositions of Theosophical themes, some deal specifically with art. An interesting idea proposed by Machell is the correspondence of colors and sounds. “The correspondence between the colors of the solar spectrum and the sounds that are employed by musicians,” he wrote, “is so strangely close that it is a matter of surprise that there has not been yet developed an art of pure color corresponding to the art of pure sound which we call music.” In Europe, the same idea, which had a long tradition, had been developed through specific references to the rules of musical composition by Lithuanian painter and composer Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis (1875–1911), who was not a member of the Theosophical Society, but was introduced to Theosophy at the Warsaw School of Fine Arts by his mentor Kazimierz Stabrowski (1869–1929). The latter was an avid reader of Blavatsky and invited to Poland Russian Theosophists, who stayed in his home and traveled with him, to make Theosophy better known in the country, and established the first lodge of the Theosophical Society in Poland.

Machell’s writings on art mostly deal with the problem that tormented Watts all his life: the question of “didactic art.” The Aesthetic Movement, popular in Machell’s time, claimed that art should not teach moral or religious values, and implied that in the opposite case, art is just dull. Machell was conscious that “didactic” art was becoming unpopular, but maintained that it should continue teaching Theosophy, even to a limited audience. “An artist who endeavors to express a mystical thought or a spiritual idea in a painting,” Machell wrote, “is necessarily appealing to a very limited public; but it may well be that his appeal will stir a desire for knowledge in the minds of some whose intelligence is awake but untrained, and also it may find a response in hearts that yearn for higher things than their education has made them acquainted with.”

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.