Some of the works and documents of the most significant early Theosophical painter perished this year when the flames destroyed Altadena’s Theosophical Society. Others survived.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 1 of 3 (published on consecutive Saturdays).

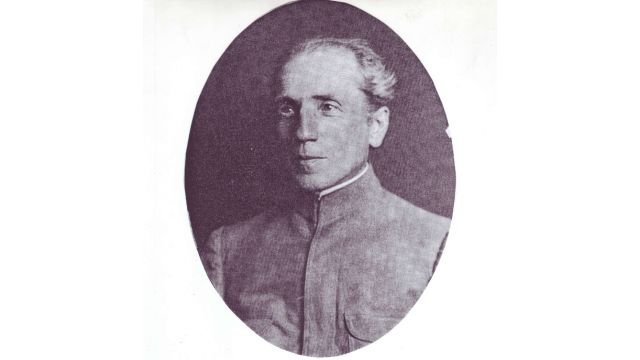

In January 2025, the horrible news came that the Los Angeles fire had almost destroyed the Altadena headquarters of the American independent branch of the Theosophical Society. Along with thousands of precious manuscripts and letters, documents and works of art by the most important early Theosophical painter, Reginald Willoughby Machell (1854–1927), were destroyed. I contacted the Society and was happy to learn that Machell’s masterpiece, “The Path,” had survived. However, other works that my wife and I had seen when visiting the Altadena headquarters in 2014 were lost.

Machell was perhaps the artist closest to Madame Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831–1891) and later became a key associate of Katherine Tingley (1847–1929), epitomizing the complex journey where Theosophy and the arts came together. Machell today is not a household name in Theosophical circles, although several Theosophists have seen one or another reproduction of “The Path.” Shortly before the time of his death in 1927, however, a then popular fantasy novelist, Kenneth Vennor Morris (1879–1937), himself a Theosophist, wrote that “in all the history of the Theosophical movement in modern times it is probable that, except the three Leaders [who for him were Blavatsky, William Quan Judge (1851–1896) and Tingley], no one has reaped a larger harvest of love and admiration’ than Machell.”

Machell was born on June 20, 1854, at Crackenthorpe, Westmoreland, England. His father, Richard Beverley Machell (1823–1903), was a canon at the Cathedral of York. The Machells were one of the most prominent families in North-West England. They claimed to descend from a fifth-century centurion, Marius Catulus, and exhibited a remote but real relationship with the British royal family. Crackenthorpe Hall, the ancestral home of the Machells, had been sold outside the family in 1786. Reginald’s uncle, Captain James Octavius Machell (1837–1902), who made a fortune as the most successful racing horse owner of Victorian times, repurchased it in 1877. Reginald’s mother, Emma Willoughby (1823–1903), came from North-West England’s rural gentry. A brother of Reginald, Colonel Percy Wilfrid Machell (1862–1916), had a distinguished military career and died in the battle of the Somme during World War I.

Percy married Countess Victoria “Valda” von Gleichen (1868–1951), a daughter of Prince Victor of Hohenlohe (1833–1891), who was a nephew of Queen Victoria (1819–1901) and a well-known sculptor, confirming how the Machell family was evolving in both high-class and artistic circles. The life of the family focused on the ancestral estate, Crackenthorpe Hall, which had its ghostly legends connected to Elizabeth Sleddall, “Peg Sneddle,” wife of Lancelot Machell (17th century), who was said to haunt Crackenthorpe Hall, and to appear to the unfortunate heads of the family before their respective deaths. Peg’s ghost was also seen driving furiously at night in a six-horse carriage, which suddenly disappeared.

Reginald was an excellent student, first at Uppingham School under famous headmaster Edward Thring (1821–1877) and then at Owen’s College, Manchester, where teachers noted his precocious inclination to the arts. Like many other promising artists, he was sent to study in Paris at the Académie Julian. “Pour le Marché de Londres,” painted while at Julian’s, shows Machell as an exceptionally gifted student.

In 1880, at age 26, he returned to London and started a painting career, specializing in portraits. With his wife Ada Mary (1848?–1931), he still visited Paris, where his first son, Henry Reginald Machell (1880–1918), was born in 1880. “Timidity,” currently at the Wolverhampton Art Gallery, is one of his first London works. “Little Angels,” a typical work of this period, is dated 1883. Eventually, Machell became a fellow of the Royal Society of British Artists and had works exhibited at the Royal Academy.

Like many young British artists during the 1880s, Machell was influenced by the symbolist painter George Frederic Watts (1817–1904). Some sources report that Watts was a member of the Theosophical Society, but there is no confirmation of this.

It is difficult to say whether Watts’ artistic influence favored Machell’s contact with the Theosophical Society. Reportedly, through a friend of one of his aunts, Machell was introduced to Madame Blavatsky. According to the artist himself, “it was in 1886 that I made the acquaintance of Madame Blavatsky in London and visited her at the house in Lansdowne Road, where she was then living. In 1888, I joined the Theosophical Society and attended the meetings of the Blavatsky Lodge, which met at the house of the foundress of the Society in Lansdowne Road, at that time. Madame Blavatsky was present on all the occasions of my weekly visits, and took part in all the proceedings, answering questions as to the teachings of Theosophy, and incidentally speaking on a great range of topics more or less connected with the main subject of study, Theosophy.”

Later, in an article published in 1918, Machell would explain his almost instantaneous acceptation of Blavatsky through reincarnation: “How can we account for the fact that many who heard her message accepted it at once, as if an old friend has come and recalled memories of former lives, if reincarnation were not a fact in nature? Even that very doctrine of reincarnation, which came to some as a strange, improbable theory, was to others a self-evident truth as soon as heard. How was that if it was indeed a new idea?”

When Machell first met her, Blavatsky had only five more years to live, but the relationship with her was crucial for the artist. It was not unimportant for Blavatsky either: she asked Machell to decorate the interior of her Regent’s Park London residence, in 19 Avenue Road, with symbols of the great religions of the East. “Adam and Eve,” completed one year after Blavatsky died, represents the new style of Machell, quite different from his old signature portrait paintings and influenced by both Watts and the Pre-Raphaelites.

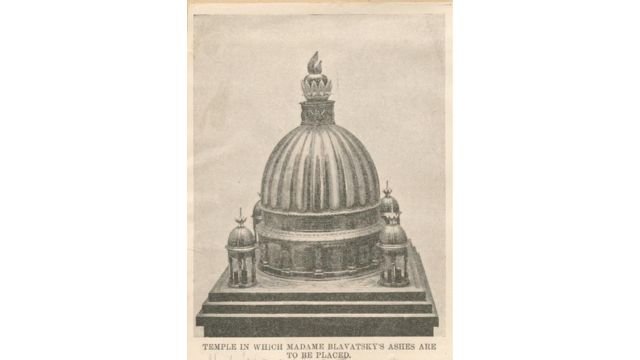

At Blavatsky’s death in 1891, her ashes were divided into three parts: one portion was kept in London, one sent to New York, and the other sent to Adyar, India. Machell was asked to design the urn for the London portion, which was executed by the Swedish Theosophist sculptor Sven Bengtsson (1843–1916). According to a contemporary account, “beneath the flaming heart rising from an unfolded lotus, wrought in silver, is a square block bearing the dates 1831, 1875, 1879, 1891, the dates of her birth, of the founding of the T.[heosophical] S.[ociety] in New York and India, respectively, and of her passing through the gateway of death. This block rests on the fluted copper dome, round the base of which runs the motto of the T.S., ‘Satyât nâsti paro dharma’ [There is no religion higher than truth]. The pedestal of the dome is carved in panels, with Theosophical emblems graven thereon; the Tau with the Serpent, the interlaced Triangles, the Triangle of the initiate, the Elephant of Wisdom, and others. The whole stands on a three–stepped square block, at each corner of which is a small dome on light pillars, with a square black clock occupying the centre of the space under the dome.”

The two-foot-high and quite impressive urn was later transferred to the headquarters of the Theosophical Society in Adyar. The urn is still there, but not Blavatsky’s ashes, which were finally deposited in the Ganges River in Benares.

After Blavatsky’s death, Machell continued his membership in the Theosophical Society and produced explicitly Theosophical paintings, including “The Dweller on the Threshold,” “The Birth of the Planet,” and “Lead, Kindly Light.” “The Dweller,” in Machell’s explanation, shows a man confronted with a threatening figure, in fact “the shadow of [him]self outside the path,” made out of his “sins.” Yet, through this vision, the initiate, who is “climbing the mountain of matter,” reaches at the same time “the vision of his own higher self—the knowledge of true occultism.”

Machell also started a career as an illustrator of Theosophy-related books, illustrating “An Idol’s Passion” (1895) and “The Chant of the Lonely Soul” (1897), two books by the American poet and novelist Irene Osgood (1875–1922), who was mostly known for her novel “The Shadow of Desire,” featuring the character of Madame Lermanoff, “an active Theosophist, and one of the most perfect pieces of unselfish womanhood.” The novel also commented, “papers and magazines devoted to Theosophy were eagerly bought up now at the principal shops and stations all over the civilized world, and yet only a few years ago such topics had been shudderingly ignored by the general public.”

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.