From Impressionist and Divisionist landscapes, the Italian artist went on to explore the paranormal, the occult, and Spiritualist seances.

by Massimo Introvigne

Not many today remember Serafino Macchiati, an Italian painter born in Camerino, in the region of Marche, on January 17, 1861. He died in Paris on December 11, 1916. Happily, twenty years after the first monograph dedicated to Macchiati, a major exhibition of the artist, curated by Francesca Cagianelli and Silvana Frezza Macchiati, has been organized at the Pinacoteca Comunale Carlo Servolini in Collesalvetti, Tuscany. It runs through February 29, 2024, and the reason I recommend it to readers of “Bitter Winter” is Macchiati’s connection with parapsychology and Spiritualism.

The exhibition’s title is “Serafino Macchiati: Moi et l’autre. The Frontiers of Impressionism Between Belle Époque Euphoria and Dramas of the Psyche.” The title needs to be explained. Some know only the “first Macchiati,” who under the patronage of his mentor Vittore Grubicy de Dragon (1851–1920) painted (mostly) landscapes and portraits, evolving from Impressionism and Post-Impressionism to Divisionism.

Grubicy, to whom the city of Livorno devoted a spectacular exhibition in 2022, was both a merchant and a critic, and a painter himself. His correspondence with Macchiati is preserved at the MART Museum in Rovereto. It includes hundreds of letters, mostly from Macchiati to Grubicy. They have been carefully studied in preparation for the Collesalvetti exhibition by Francesca Cagianelli and Dario Matteoni. The letters clarify Macchiati’s relationship with artists interested in Spiritualism and other forms of alternative spirituality, including Gaetano Previati (1852–1920) and Giacomo Balla (1871–1958). Balla, whose interests for Theosophy and Spiritualist seances are well documented, spent seven months as a guest of Macchiati in Paris.

Paris is indeed where the “second Macchiati” moved first to painting the life of the city with a gaze that was both social and socialist, as he became a close friend of poet and Marxist activist Henri Barbusse (1873–1935). By achieving a formidable success as an illustrator of novels, including by the Spiritualist creator of Sherlock Holmes, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930), Macchiati developed a taste for depicting crimes, the “artificial paradises” of drugs, the horror, the paranormal, and Spiritualism. It is a new and important result of Francesca Cagianelli’s exploration of Macchiati, documented in the Collesalvetti exhibition, that the “first” and the “second” Macchiati cannot be separated, and a “red thread” connects the distinct stages of the Italian artist’s career, which may thus be read as a whole.

Macchiati’s was a struggle for independence and modernity, best represented by his attitude to illustration. He did not see the illustrator as ancillary or subordinate to the writer but as a co-author. The exhibition documents Macchiati’s work as illustrator of books and magazines, insisting on the importance of his cooperation with the French “Je sais tout.” It is in this magazine that in 1905 the novel “Moi et l’autre” by Jules Claretie (1840–1913) was first published. Macchiati illustrated both the “Je sais tout” series and the two book versions published by Pierre Lafitte in 1908 and 1912. In fact, the correspondence with Grubicy demonstrates that Macchiati started discussing the work with Claretie while it was being written, before the publication.

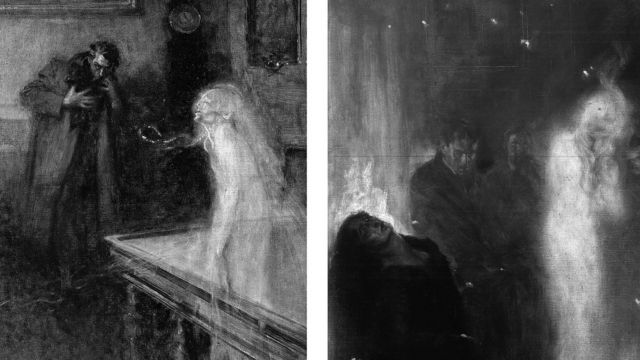

“Moi et l’autre” is a classical story of split personality, a theme explored by French-speaking psychiatrists of the Belle Époque and also used by some to explain the Spiritualist mediums. In the novel, it is a young artist, André Fortis, who alternates between two different personalities and experiences hallucinations and phenomena similar to those described in contemporary literature about the paranormal and Spiritualist seances. In what is probably the best illustration by Macchiati, during a dinner party Fortis “projects” the head of his wife wrapped in a circle of light.

Macchiati also illustrated for “Je sais tout” “The Man Who Saw the Devil” by Gaston Leroux (1868–1927) and “Notre enquête sur l’au-delà” (Our Investigation of the Afterlife) by journalist André Arnyvelde (1881–1942), which the magazine published in 1912. This allowed Macchiati to illustrate Satanic rituals, ectoplasms, and seances.

Curiosity for and even belief in the paranormal were regarded during the Belle Époque as a way of being truly modern and remaining in touch with the cutting edge and perhaps the future of science. Prominent scientists shared this attitude, but it was the artists who consigned it to future generations through evocative works who still speak to us of mysteries unsolved and unknown realms. Macchiati was an important part of this movement at the crossroad of art, literature, and esotericism.

All those regarding the movement as relevant should be deeply grateful to the organizers of the Collesalvetti exhibition (whose catalogue has been published by Silvana Editoriale) for preserving the memory and the taste of a significant character from an extraordinary epoch of Europe’s cultural history.

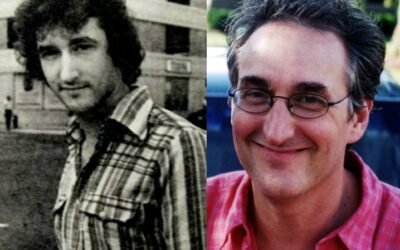

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.