Allegedly, on July 5 a paragraph of a pre-written speech by the Pope where he supported freedom in Hong Kong was not read by Francis. To avoid further wild speculations, the Vatican may publish the text of the 2018 China deal.

by Massimo Introvigne

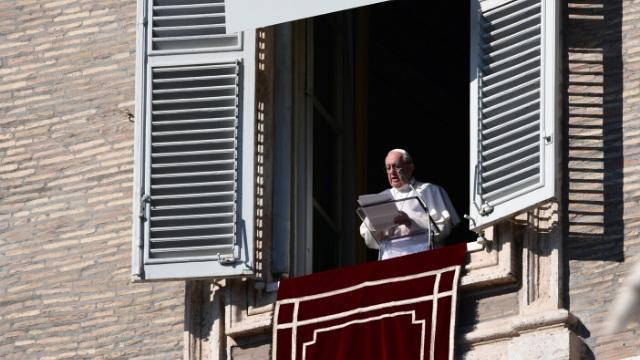

On July 5, a mysterious incident that would have pleased a Dan Brown happened in the Vatican. Speeches by the Pope are distributed to journalists “embargoed,” meaning that media can quote them only after the Pope had pronounced them. In the past, journalists who violated the embargoes lost their credentials with the Vatican.

Allegedly, the embargoed text in Italian of the usual Sunday speech of Pope Francis included a paragraph about Hong Kong. In English, it reads as follows: “In the last few days, I have followed with a special attention, and not without concern, how a complicated situation was developing in Hong Kong. First of all, I would like to express my sympathy and closeness to all those living there. What is being discussed in these days concerns delicate matters, affecting everybody’s life. Accordingly, it is easy to understand how feelings can be strong. I wish therefore that all those involved would be able to confront the issues in a spirit of wisdom and genuine dialogue. This requires courage, humility, non-violence, and respect for the dignity and rights of all. It is my desire that social and, particularly, religious life may manifest themselves in full and genuine freedom, as indeed several international documents mandate. My prayer remains constantly with the Catholic community and all people of good will in Hong Kong, so that they may build together a prosperous and harmonious society.”

When Pope Francis read this speech, however, the paragraph was omitted. Although the text was first leaked by a journalist known for his hostility to Francis, there is no reason to doubt its authenticity, nor has the Vatican denied that it is one of the usual pre-written speeches distributed under embargo. The text was quite moderate, but the reference to “full and genuine freedom” and to “international documents” China should respect might have been annoying for the Chinese, although it was balanced by the reference to a “harmonious society,” an expression frequently used by President Xi Jinping.

Critics claim that, in the few hours between the distribution of the embargoed text to the media and the speech, China intervened. This is not impossible, but would have been extraordinarily quick. One astute observer saw in the incident what in Italian I would be tempted to call, with all due respect, “avvertimento mafioso,” or mafia-style warning. According to this interpretation, the Vatican let the text circulate to warn the Chinese of what the Pope could say if they do not exercise some restraint.

All this happened in a climate where the Pope’s silence on Hong Kong was often criticized, and speculations about the renewal of the Vatican-China deal of 2018, due in September 2020, abound.

Pope Francis has enemies who are against him for reasons totally unrelated to China, and I personally do not believe in their sensational revelations on China’s alleged monetary support to the Vatican or clauses on Hong Kong in the 2018 agreement. But speculations run wild because the 2018 text is secret.

My proposal would be, before a renewal is signed, as it seems probable, or not signed, to make its text public. This would be the most effective way to eliminate rumors, fake news, and speculations. The objection that secrecy is part of the agreement itself is not a valid one, since we know that renewal is not automatic and, when renewing an agreement, clauses can always be renegotiated.

The main objection is that secret deals are part of diplomacy, and may serve a good purpose. However, Pope Francis has called time and again for a deep reformation of how the Vatican institutions operate, and advocated a new climate of transparency and synodality. It seems that very few people, even in the Vatican itself, not to mention within the Chinese Catholic Church, have read the agreement. What is happening on the ground, as Bitter Winter documents regularly, is, to say the least, contradictory. Persecution of priests and bishops critic of the CCP, and sometimes even of some who are not critic of the regime, has not stopped.

The Vatican’s is not just another government. In the name of transparency and synodality, publishing the text of the agreement, or at least circulating it among cardinals and bishops, would contribute to detoxify what is increasingly becoming a toxic, dysfunctional situation, and to protect the Pope himself from his most vitriolic critics.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.