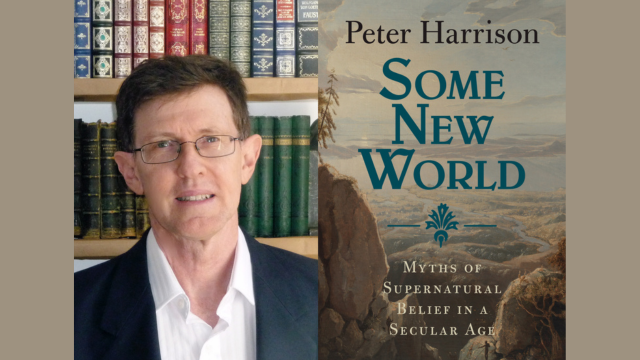

The Australian scholar has produced what may well be the most important book on religion in recent years.

by Massimo Introvigne

Peter Harrison’s outstanding “Some New World: Myths of Supernatural Belief in a Secular Age” (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2025) is not just a book—it’s a philosophical scalpel, slicing through centuries of intellectual sediment to expose the fragile bones of modernity’s most cherished assumptions. It’s dazzling, dense, and deliciously subversive. If you thought you knew what “belief” meant, prepare to be unmoored.

The book opens with David Hume, Enlightenment icon and patron saint of skepticism, who famously dismissed miracles as violations of the natural law all peoples believe in and therefore inherently unbelievable. But Harrison calls Hume’s bluff. The majority of people in Hume’s own time believed in miracles as much as they believed in natural laws—as do most humans today, Harrison notes. Hume’s real move was not statistical but sociological: he shifted from the number of witnesses to their supposed quality. Miracles, he claimed, were the domain of the ignorant—Africans, Asians, and medieval Europeans—while the enlightened elite knew better. Harrison doesn’t flinch from pointing out that some of Hume’s remarks would earn him a swift cancellation today.

But Harrison’s real quarry is deeper. He argues—brilliantly—that “belief” as we understand it today is a modern Western invention. In premodern Europe, people didn’t “believe” in abstract propositions; they believed in people. Belief was relational, not epistemological. It was about trust, not syllogisms. The same goes for “faith,” which was once a synonym for loyalty and confidence, not assent to doctrinal statements.

This matters because it reframes the entire history of Christianization. Early converts didn’t grasp the Trinity or transubstantiation. They had “fides implicita”—implicit faith in the Church and its teachers. They trusted the community to get the theology right. “Christianisation in early Medieval Europe was not understood in terms of adoption of a distinctive set of Christian beliefs,” Harrison writes. Theology itself was suspect for centuries, a term reserved for pagan speculation until Abelard dared to rehabilitate it.

And no, Harrison insists, this wasn’t an apology for ignorance. Medieval Catholics believed that faith would awaken reason, not obstruct it. “Fides quaerens intellectum”—faith seeking understanding—was their motto. Trust came first, but it was the beginning of a journey toward intellectual refinement. Converts were expected to grow in knowledge, not wallow in blind obedience. By the way, early Christian apologist Tertullian never said “Credo quia absurdum,” “I believe because it’s absurd.” As Harrison illustrated in a previous article, this was yet another Enlightenment fabrication.

Harrison anticipates a common objection to his theory that “belief” was originally interpreted as trust: didn’t Catholic theologians offer “proofs” for the existence of God long before the Reformation? Yes—but these were not modern-style apologetics aimed at persuading skeptics. They were “spiritual exercises,” preaching to the converted. The very concept of “atheism” didn’t appear until the 16th century. When unbelief did arise, the standard rebuttal was “universal consent”—the idea that all peoples, everywhere, believed in a divine source. Protestants dismissed this too, fearing it lent credence to Catholic ideas of tradition. Locke and the Enlightenment rebranded it as “clerical imposture.”

Enter the Protestants, who launched a crusade against “fides implicita,” mocking it as “la foi du charbonnier”—the coalman’s faith. They demanded intellectual assent, not trust. Baptism now required doctrinal comprehension. The word “belief” was redefined to mean agreement with specific theological propositions. Ironically, this made belief more vulnerable. Trust can’t be disproven by logic; doctrinal statements can. By trying to rationalize faith, Protestants exposed it to the very skepticism they hoped to avoid.

This shift had seismic consequences. “Religions” (plural) became sets of beliefs competing with other belief systems. “Supernatural” was carved out as the irrational residue of faith—miracles, angels, divine interventions. And “progress,” once a moral journey of the soul, became a sociological ladder: from magical to religious to scientific. Auguste Comte’s ghost still haunts undergraduate textbooks, Harrison notes, perpetuating colonialist assumptions about non-Western societies stuck in the “magical” stage.

And let’s not forget the natural/supernatural binary itself. Harrison shows that this opposition—and the idea that the “supernatural” is inherently irrational—is a modern invention. Before Locke and the Enlightenment, such a dichotomy would have made little sense. The world was enchanted, yes, but not divided into neat epistemological categories. The supernatural (by any other name) wasn’t a violation of reason—it was part of the fabric of reality.

Harrison dismantles another myth: the war between science and religion. Galileo’s trial, often cited as Exhibit A, was massively weaponized for this purpose only in the 19th century. Many scientists, even then, were devout. They saw the elegance of nature as evidence of divine craftsmanship. Reason itself was once revered as a divine gift, which the Protestants found more trustworthy than popes or councils. But as its divine origin faded from memory, reason became a secular tribunal—one that eventually condemned Protestant doctrines as irrational too.

Harrison is no nostalgic reactionary. He acknowledges modernity’s gifts. But he warns against monochrome narratives of progress. One of his most provocative claims is that science, too, relies on “fides implicita.” Most of us don’t understand quantum mechanics or vaccine development. We trust scientists—until we don’t. The COVID pandemic revealed a crisis of trust. Anti-vaxxers didn’t abandon “fides implicita” either; they redirected it to conspiracy theorists and influencers. Trust didn’t die—it changed address.

As a scholar of new religious movements, I find Harrison’s thesis electrifying. He doesn’t mention my field, but I’ll extend his argument: many new religions are a renaissance of “fides implicita.” Converts don’t join because they’ve dissected theological treatises (although some may read them later). They join because they trust a guru, a prophet, a community. Just like early Christians and Muslims. The intellectual scaffolding may come later—or not at all.

So, is “fides implicita” obsolete? Has secular science vanquished religion? Harrison—and I—say: not so fast. Belief, in its ancient form as trust, is alive and well. It’s just wearing new clothes.

And if you think this book is merely a historical romp, think again. It’s a mirror held up to our modern certainties, asking whether we really understand what we mean when we say we “believe.” Harrison’s answer is subtle, subversive, and—yes—somewhat miraculous.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.