The Swiss tragedy of 1994 was repeated in 1995 in France and in 1997 in Quebec.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 7 of 9. Read article 1, article 2, article 3, article 4, article 5, and article 6.

As we saw in the previous articles of this series, the leadership and the core membership of the Order of the Solar Temple self-destroyed themselves through the homicides and suicides in Quebec and in the Swiss villages of Cheiry and Salvan of October 4 and 5, 1994.

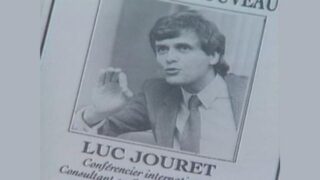

The dichotomy between suicide and murder is only part of the story, if we believe four documents sent by the OTS to the press, to former members, and to scholars through Patrick Vuarnet (1968–1995), a member of the OTS and the son of French former skiing champion turned industrialist Jean Vuarnet (1933–2017). The documents were accompanied, in some cases, by videos and by a fifth document in which Di Mambro deplored “the barbarous, incompetent and aberrant conduct of Doctor Luc Jouret” who had transformed in a “veritable carnage” what should have been a glorious Transit.

The documents, collectively referred to as “the Testament,” mentioned that some “traitors” had been “executed.” However, they also suggested that together with the killed traitors (including the Dutoits in Quebec, Di Mambro’s son Elie, and possibly Falardeau) and the core members strong enough to understand the full implications of the Transit, there were also weaker Templars. The latter did not disagree with the idea of the Transit (although they may have figured it as something different from a suicide), but needed some “help” in order to accomplish it. The Testament’s description of the different types of deaths was consistent with the findings of the Swiss official investigation .

Interestingly, very few former OTS members re-interpreted the OTS within the frame of the anti-cult worldview. Those few included Thierry Huguénin, who barely escaped the Swiss killings. The majority of the former Templars continued to express sympathy for the OTS, and some explicitly told the Swiss judges that they regretted not having been “called” by Di Mambro to participate in the Transit.

In fact, it seemed that Di Mambro had planned the survival of some “witnesses” by establishing in Avignon on September 24, 1994, yet another organization, the ARC. ARC’s meaning was Association for Cultural Research for the external world, and Alliance Rosy-Cross for initiates. The idea of having both a “public” and a “secret” name for the same organization was consistent with Di Mambro’s style and his paranoid need for secrecy.

One of the speakers at the Avignon meeting founding ARC was Michel Tabachnik, the musical conductor we had met before as a friend of Di Mambro. Despite his personal dislike for Luc Jouret that, he later claimed, prevented him from formally joining the OTS, Tabachnik had been an occasional speaker for the movement in Quebec and had kept in touch with Di Mambro. The only public figure to survive the 1994 tragedy, Tabachnik subsequently was accused by the anti-cult movement and by some media of being the hidden leader of the OTS or at least the successor of Di Mambro. His musical career was temporarily compromised.

In 1996, a criminal action was started in Grenoble, France, against Tabachnik regarded as a possible ideological source of the tragedies through his speeches and writings. He insisted that he never approved the suicides and homicides, and regarded himself, rather, as a “scapegoat.” He was eventually acquitted of all charges.

Notwithstanding the continued police interest in what was left of the OTS, a second tragedy happened in 1995. On December 23, sixteen members of the OTS, including Patrick Vuarnet and his mother Edith Bonlieu (1934–1995), a former Olympic skier like her husband Jean Vuarnet, and three children of the members were found dead in the Vercors mountains near Grenoble. The first findings of the French investigation concluded that at least some of the dead (and certainly the children) were murdered. At any rate, all died by pistol shots.

The organizer of the tragedy, and the leader of what was left of the OTS in Europe after Di Mambro’s death, appeared to have been Swiss psychotherapist Christiane Bonet (1945–1995), seconded by two French policemen in active duty who were members of the OTS, Jean-Pierre Lardanchet (1959–1995) and Patrick Rostan (1966–1995). French investigators concluded that the victims were killed by Lardanchet and by a Swiss OTS member, André Friedli (1956–1995), who finally shot themselves.

In a third incident discovered on May 23, 1997, in Saint-Casimir, Quebec, five members of the OTS committed suicide. These were Bruno Klaus (1947–1997), the former husband of vocal apostate Rose-Marie, Pauline Rioux (1943–1997), Didier Quèze (1957–1997), his wife Chantal (née Goullot, 1955–1997) and his mother-in-law Suzanne Druau (1934–1997). Druau was suffocated by a plastic bag (a trademark of OTS deaths), while the others asphyxiated from the smoke before being reached by the fire set to the home.

According to the Quebec police, there was no evidence of violence or poisoning although the victims had consumed significant doses of tranquillizers. The three children of the Quèze couple were permitted to choose whether they would participate. They decided not to die, were drugged during the adults’ suicide, and survived.

The third incident basically destroyed the OTS. Former members who survived and remained loyal to Di Mambro’s idea are still alive today, but despite occasional media claims to the contrary no organized OTS activity has continued.