The former Australian Prime Minister tells us why he changed his mind on several Chinese issues and why we should take Xi’s Marxism seriously.

by Massimo Introvigne

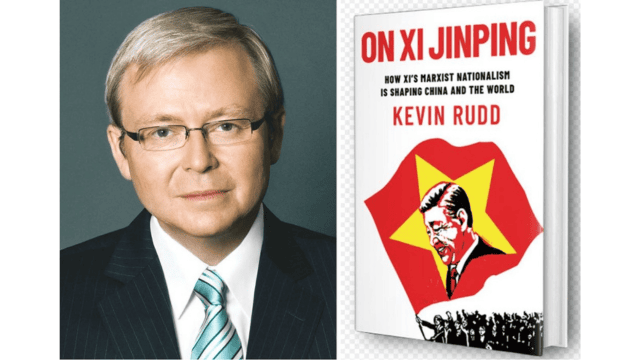

Reviewing Kevin Rudd’s new book “On Xi Jinping” (New York: Oxford University Press, 2024) is an impossible task. In more than 600 pages, he offers to us an encyclopedia on Xi Jinping’s thought on everything and a summary of Rudd’s own evolving views on China. This is, thus, not a review but a commentary on some of the book’s main themes.

First, Kevin Rudd matters. He is the former Australian Prime Minister and the current Australian Ambassador to the United States. He is also willing to publicly attest his Christian faith, which is not common for a Labor politician in Australia. Recently, he got his PhD at Oxford, and the book is a revised version of his doctoral dissertation. One thing Rudd is not is a biased and uncompromising anti-Communist. In fact, he defines himself as “a Christian socialist,” while admitting that this is an old-fashioned position that is becoming rare among Christians.

For years, Rudd advocated “strategic trust” between the West and China, which he presented not as naïveté but as willingness to take seriously the statements by the Chinese regime, totalitarian and cruel as it might be, that it was not interested in creating a major world conflict. No longer now. “Strategic trust” has been replaced in the book by the ideas that the only way to protect Taiwan is military, that a “strategic confusion” making China uncertain about how the West will react to military aggressions may be the best option in the near future, and that Xi Jinping no longer believes (if he ever did) that a major war should be avoided at all costs.

These are conclusions, but they come after hundreds of pages of detailed analysis of Xi’s ideology. Readers of “Bitter Winter” will find there two familiar themes, which should be obvious to anybody reading the writings of Xi but aren’t to many Western media and politicians.

The first is that Xi Jinping is a committed Marxist and Communist, much more than any of his post-Mao predecessors. Most of the mistakes made by Westerners in dealing with China derive from the refusal of acknowledging that Xi is really an orthodox and almost fanatical Marxist rather than simply a pragmatist going through the motions of being Communist. Ninety million members of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) should download an app allowing them to study Xi’s thought and Marxism daily, and they should prove they use it religiously—or else. Marxism, Rudd tells us, does not have a clear distinction between domestic and foreign policy. He calls Xi’s “Marxist nationalism”—but so was Stalin’s brand of Communism. And Rudd can use hundreds of quotes from Xi to show how for him Marxism is compatible with having in China tycoons and billionaires (as long as they are strictly controlled by the Party).

The second key point in the book is that Xi had a leading role in the CCP’s analysis of the collapse of the Soviet Union. To many, it was evidence that Marxist theory predicting that Communism could not fail had been proved false. To Xi, it was evidence of the contrary. It was because the Soviet leaders had become less strictly Marxist and less ideological that they fell, a mistake the CCP should avoid at all costs, Xi said. He added, since the years after the fall of the Berlin Wall, that Communist parties can only survive by putting their trust in a strong leader, and he obviously had in mind himself.

The book is not specifically about religion, but it reiterates that part of Xi’s analysis of what went wrong with Eastern European Communism is that it left free rein to the civil society, including in some countries to Christian churches, which would eventually destroy it. No such mistake should be repeated in China.

Since ideology matters for Xi Jinping, Rudd’s book matters for those who want to understand him. The alternative is reading daily Xi’s quite boring prose.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.