Henrik Bogdan and Manon Hedenborg White’s edition of Hirsig’s diaries demonstrates that Leah was not just a footnote in Crowley’s life but a significant force in her own right.

by Massimo Introvigne

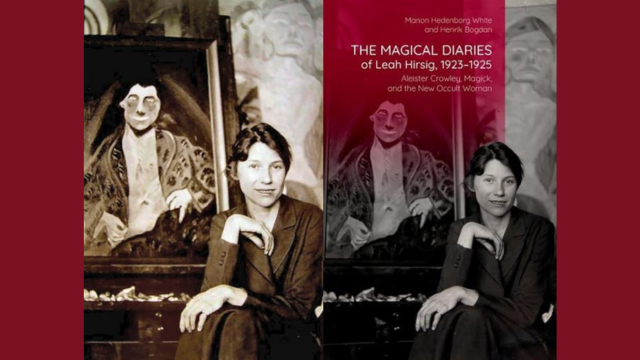

In the annals of Western esotericism, few figures are as compelling—and as long obscured—as Leah Hirsig. With “The Magical Diaries of Leah Hirsig, 1923–1925: Aleister Crowley, Magick, and the New Occult Woman” (New York: Oxford University Press, 2025), editors Manon Hedenborg White and Henrik Bogdan have not only published the first complete and annotated edition of Hirsig’s diaries but also reconstructed a biography that had, until now, remained frustratingly elusive. The result is a landmark work that offers a vivid portrait of a singular woman and a critical contribution to the study of gender and spirituality in the early twentieth century.

Born in Trachselwald, Switzerland, in 1883, Leah Hirsig emigrated to the United States with her family at two. Raised in New York City, she became a schoolteacher—a respectable profession for a woman of her time. But Hirsig was never content with convention. In 1918, one of her older sisters introduced Leah to Aleister Crowley, who then lived in Greenwich Village.

Crowley said they were already making love by their third meeting in January 1919. In 1920, she gave birth to her and Crowley’s daughter, Anna Leah (“Poupée”), who would survive only for eight months. Crowley, the self-styled “Great Beast 666” and prophet of Thelema, saw in Hirsig not only a lover but a spiritual partner. In 1920, she was consecrated as his “Scarlet Woman,” with her magical name Alostrael. This title was not merely symbolic—it marked her as Crowley’s feminine counterpart in ritual and revelation, and the earthly avatar of Babalon, the Thelemic goddess of sacred transgression.

Hirsig’s dedication was absolute. This commitment was a spiritual declaration and a rejection of bourgeois morality. Hirsig was embracing a path of ecstatic self-destruction and divine transformation—a path few dared to walk.

In 1920, Hirsig and Crowley founded the Abbey of Thelema in Cefalù, Sicily. Here, Hirsig’s role as initiatrix and spiritual steward reached its zenith. She helped Crowley through periods of illness, addiction, and despair, and presided over his attainment of the grade of Ipsissimus—the highest level in his magical system. Crowley acknowledged her power himself.

Hirsig was not merely a consort or assistant. She was the beating heart of the Thelemic experiment in Cefalù, guiding rituals, transcribing texts, and holding the community together through chaos. Her magical practice was rigorous and deeply personal, blending invocations of Ra Hoor Khuit with meditations on suffering, sacrifice, and divine union.

Yet the Abbey was also a site of scandal. The death of Raoul Loveday, a young English disciple, and rumors of bizarre rituals led to public outrage and Mussolini’s eventual expulsion of Crowley and his followers from Italy in 1923.

The diaries presented in this volume cover 1923 to 1925, a period of transition and transformation for Hirsig. By 1924, she had been replaced as Scarlet Woman, yet she remained devoted to Thelema. Her writings from this time are raw, poetic, and often painfully honest. They chronicle her magical practices, her emotional struggles, and her attempts to renegotiate her role within the movement.

By the late 1920s, Hirsig’s relationship with Crowley had frayed beyond repair. In 1930, she formally withdrew from the Thelemic movement. She returned to teaching, in Bern, and lived quietly until her death in Meiringen, Switzerland, in 1975.

Hirsig’s entries reveal a woman grappling with spiritual doubt, romantic disillusionment, and physical hardship. She documents her diet, health, and sexual encounters with unflinching candor. She invokes Chaos as her divine consort and recommits herself to the Great Work, even as her relationship with Crowley deteriorates.

The editors have supplemented the diaries with a selection of previously unpublished letters and poems between Hirsig and Crowley. These materials offer further insight into their volatile partnership and the broader dynamics of the Thelemic community. They also highlight Hirsig’s literary gifts—her prose is often lyrical, and her imagery is haunting.

Manon Hedenborg White and Henrik Bogdan are uniquely qualified to undertake this project. White, known for her work on gender and esotericism, and Bogdan, a leading scholar of the Thelemic current, bring both rigor and empathy to their editorial work. Their introduction situates Hirsig within the context of early twentieth-century occultism, the New Woman movement, and the shifting roles of women in religious leadership.

They argue convincingly that Hirsig embodied the ideals of the New Woman: educated, sexually autonomous, spiritually radical. She lived, loved, and suffered on her terms, defying the constraints of her era. Yet she also faced the limitations imposed by gender inequality—even within a movement that claimed to transcend societal norms.

The editors’ reconstruction of Hirsig’s biography is a significant scholarly achievement. For decades, her life was shrouded in mystery, overshadowed by Crowley’s mythos. But White and Bogdan have pieced together her story from archival sources, letters, and unpublished manuscripts, offering the most complete account of her life and legacy.

“The Magical Diaries of Leah Hirsig, 1923–1925” is more than a historical document. It is a spiritual autobiography, a feminist testament, and a literary artifact. It reveals the inner life of a woman who dared to live as a goddess—and who paid the price for it.

For scholars interested in religion, gender, and esotericism, this book is essential. For those curious about the boundaries of mysticism, it provides a breakthrough. And for anyone seeking to understand the human side of spiritual extremes, it makes a lasting impact.

Leah Hirsig was not a footnote in Crowley’s life. She was a force in her own right. Her voice has finally been restored thanks to White and Bogdan—and it sings with power, pain, and transcendence.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.