All of a sudden, after Shinzo Abe was assassinated, the nisei issue became prominent in Japanese public discourse.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 3 of 4. Read article 1 and article 2.

On July 8, 2022, former Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe was assassinated by a man called Tetsuya Yamagami. The assassin claimed he wanted to punish Abe for his friendly attitude towards the Unification Church. Yamagami reported that his mother, a member of that Church, went bankrupt in 2002 because of her excessive donations and neglected to take care of her children.

In the May 2025 issue of “Nova Religio,” Japanese religion expert Adam Lyons published an article discussing how public opinion in Japan largely viewed Yamagami as a “victim” of the Unification Church. This incident highlighted the topic of “shukyo nisei,” or “nisei” (“the second generation of religion members”) in Japanese public discourse.

The issue is not new. Lyons highlighted in a conference paper a notable and impactful autobiographical novel, “Human Fate” by Kojiro Serizawa (1896–1993), published in fourteen volumes during the 1960s. The novel’s accusations against Tenrikyo, one of Japan’s oldest and largest new religions, resonate with Yamagami’s statements regarding the Unification Church. Serizawa asserts that his father destroyed their family through contributions to Tenrikyo, leading to Kojiro (referred to as Jiro in the novel) being entrusted to his grandparents so the father could dedicate himself to the religion’s missionary efforts.

Only after Abe’s assassination was the nisei issue recognized as a significant concern within Japanese society. “Nisei” does not`refer only to individuals raised in the Unification Church, regardless of their membership status (Yamagami never joined). Other religions are involved.

The criticism identified the Jehovah’s Witnesses as another primary target in addition to the Unification Church, but also extended to other new religions such as Happy Science, involved the largest Japanese lay Buddhist group, Soka Gakkai, and ultimately targeted conservative religions more broadly, including Evangelical Protestantism.

This perspective was evident in the government’s guidelines concerning “religious child abuse,” which drew criticism from United Nations Rapporteurs. The guidelines viewed certain practices, not connected with the Unification Church, as abusive—like forbidding children from celebrating birthdays (a practice typical of Jehovah’s Witnesses), attempting to prevent minor daughters from having abortions (common across all conservative Christian denominations), and sending minors to confessions where they might discuss violations of sexual norms (primarily seen in Roman Catholicism).

In essence, all those educated according to principles that contradict what Lyons calls Japan’s “dominant ethos of normative secularism” are categorized as nisei and viewed as victims of their parents’ religious indoctrination.

Lyons argues that Abe’s assassination marked the beginning of a second wave of “cult wars” spanning from Japan to other countries, including the United States. This followed the initial “cult wars,” which pitted anti-cult activists against scholars of new religious movements during the 20th century.

Lyons notes that the distinction between the first and second cult wars lies in the focus of the anti‑cultists. While the first wave was primarily concerned with the young adults who converted to new religious movements, the current wave emphasizes those born into alternative religions rather than converted.

Since he intends to define the differences between the second cult wars and the first, Lyons emphasizes that, when focusing on the converts, the primary tool of the anti-cultists was the theory of brainwashing. The issue of brainwashing and mind control is not especially prominent in most nisei accounts. Nisei blame their bad luck in the “parent lottery.”

The brainwashing narrative remains a vital part of the public debate promoted by the National Network of Lawyers Against Spiritual Sales (NNLSS), which is the oldest organization opposing “cults” and the Unification Church. This group ensured that allegations of mind control were part of the court case resulting in a first-degree verdict to dissolve the Church as a religious corporation in March 2025. Nevertheless, Lyons notes that the NNLSS’s “traditional” anti-cult stance now faces competition in Japan from new organizations that advocate for nisei, and their rhetoric differs significantly.

Another difference between the first and second cult wars is that, as Lyons notes, most Japanese scholars of religion align with the anti-cultists. In the first cult wars, scholars of new religious movements played a leading role in securing victories for groups labeled “cults” in American and European courts of law.

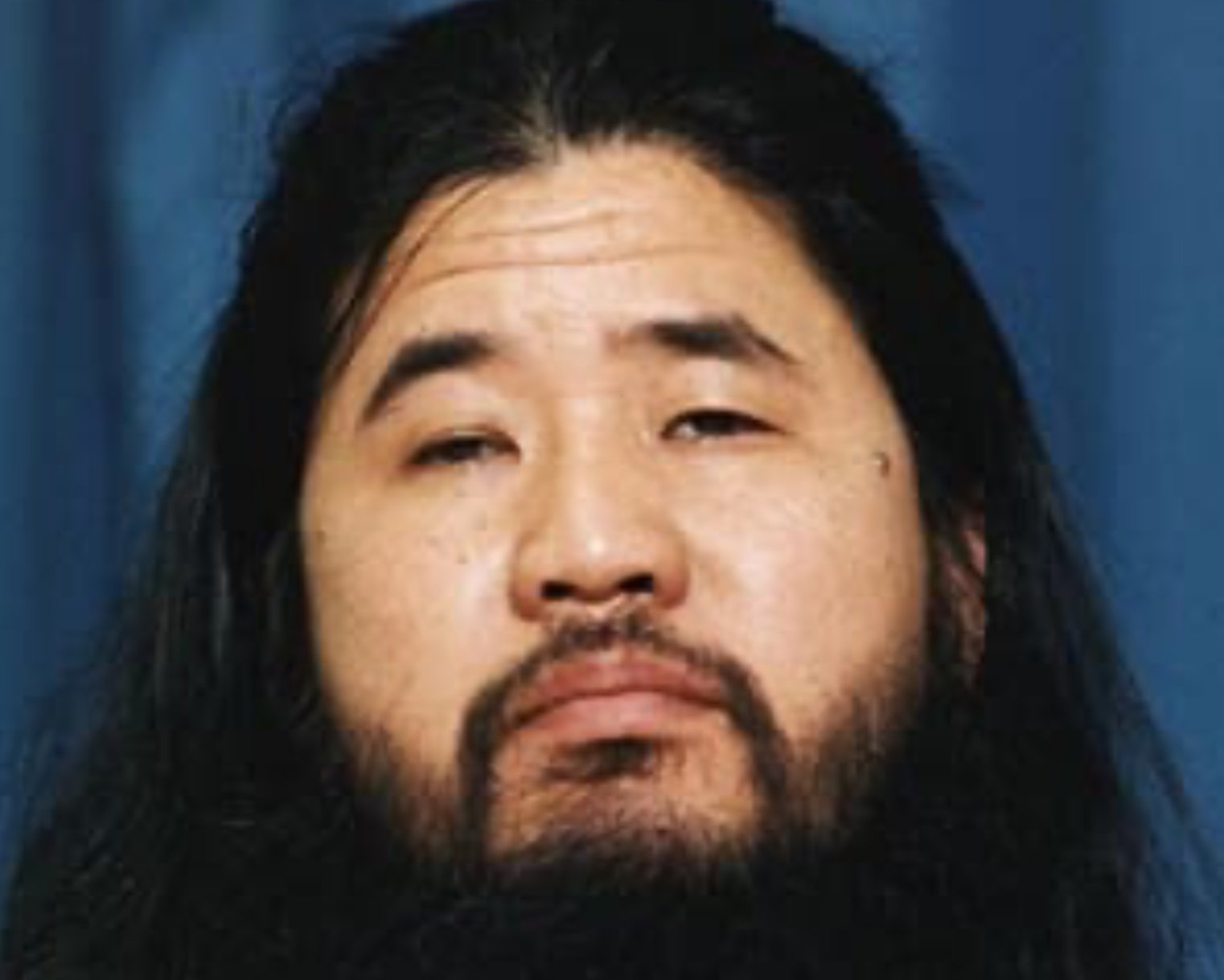

Lyons does not elaborate on the reasons for this surprising situation in Japan. I believe one reason is connected to the crimes committed by the new religious movement Aum Shinrikyo, culminating in the deadly sarin gas attack in the Tokyo subway in 1995. Some Japanese scholars participated in Aum Shinrikyo events.

After Aum’s crimes were revealed, it became impossible for Japanese scholars sympathetic to movements portrayed by the media as “dangerous cults” to continue their academic careers without facing harassment. Most scholars jumped on the anti‑cult bandwagon. Young Japanese scholars who oppose the anti-cult ideology often present at conferences only outside Japan and in English.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.