There is no happy end in “The Elected of the Dragon.” Both Clotilde and her lover, American President Garfield, incur the wrath of the Ninth Circle.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 4 of 6. Read article 1, article 2, and article 3.

In “The Elected of the Dragon,” Garfield is depicted as a bad character, but with some redeeming features. He is genuinely in love with Clotilde, and tries to protect her by terminating her dangerous service as High Priestess of the Ninth Circle. Clotilde and the Dragon himself do not appreciate the well-intentioned move, and plot the ruin of Garfield. They are helped by a group of French politicians who formed the tip of the Ninth Circle, including Jules Ferry (1832–1893), who was twice Prime Minister of France, Jules Grévy (1807–1891), at that time the French President of the Republic, and Pierre Emmanuel Tirard (1827–1893), who was also Prime Minister for two short periods.

This group of Satanist politicians convinced Garfield to create an autonomous American branch of the Grand Lodge of the Illuminati. The organization, in turn, would get him elected as President of the United States.

Garfield, thus, should leave the real center of the Ninth Lodge, Paris, where Grévy became his successor, but the revenge of Clotilde and the Dragon was not finished. After having been elected as President, Garfield was killed on September 19, 1881, in an attack in Baltimore, whose organizers of course took their orders from the Grand Lodge of the Illuminati, or so the book claimed.

Clotilde believed she had won her battle, but in fact she had lost, and will later regret bitterly her time with Garfield. Grévy tried to summon the Dragon by himself, dispensing from her services. Other initiates started refusing taking orders from a woman. A painter, Chéret, openly rebelled, forcing Clotilde to a duel with a foil in Bern, which was mortal for the artist since the Elected was still under the protection of the Dragon. The allusion, here, seems to be to popular Parisian painter Jules Chéret (1836–1932), who, however, did not die in a duel with a woman in the 19th century but peacefully in his villa in Nice many years later, in 1932.

The worst problems for Clotilde began when a priest, a certain Father Mazati, was admitted into the lodge. Mazati consecrated the holy wafers to be later desecrated, thus eliminating the problem of stealing them from churches. The priest began to evoke himself the Dragon, summoning him “in the name of the Holy Trinity.” This surprised Clotilde, who wondered how “the Spirit [Satan] was compelled to surrender to an evocation made in the name of an inferior Catholic divinity.”

Serious doubts started to torment Clotilde, although she was still busy with political intrigues, which included manipulating the French elections of 1881 and organizing the assassination of Tsar Alexander II (1818–1881) in Russia.

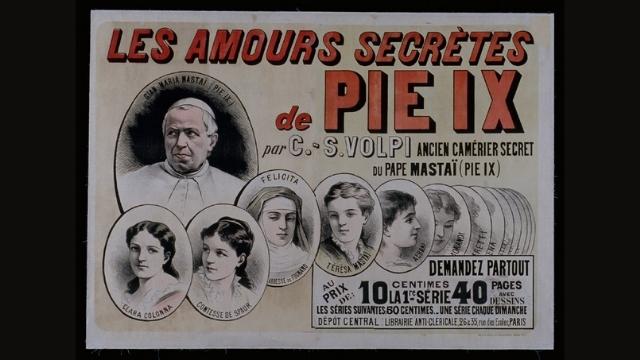

Under the impulse of the Dragon, which appeared to her in a visible form, and sometimes animated his statue in the lodge, Clotilde also gave inflammatory anticlerical speeches. She reported that these speeches were plagiarized for his books, including “The Secret Lovers of Pius IX,” by a certain Léo Taxil (at that time still a Freemason and not yet “converted” to Catholicism), who did no more than copy the “more perfidious and shameless” discourses pronounced by the young Italian woman in the lodge.

Finally, however, Clotilde decided to ask the Dragon why he had to obey a wretch such as Father Mazati. The Dragon, as the Catholic reader to which the book was directed had already understood, at this point should have confessed that the power of the priesthood of the Roman Catholic Church, even in its worst priest, was stronger than his own power was. He did not want to admit this, however, and more simply organized the ruin of Clotilde.

A conspiracy was thus prepared against the Italian inside the Satanist organization. Slogans were spread such as “No more skirts at the Masonic Table” or “Down with Clotilde Bersone!” The poor Italian girl was sent to Grenoble to work as an upscale prostitute in a brothel secretly managed by Freemasonry, where she should try to steal the secrets of the local powerful.

Clotilde was still obedient, and did what she was told. She found some form of comfort in the fact that the “filthy establishment” at least had “some exterior décor, for the use of upper bourgeoisie and high-ranking military”: “it was not exactly the vulgar public brothel.”

She performed her job as a prostitute, and did it well, obtaining important revelations from her clients, which she passed to the Ninth Circlers in Paris. They eventually informed her that her exile was finished, and they were waiting for her in Macon. But Clotilde was afraid that in Macon she would simply be assassinated.

Besides, reflecting on the episode of Father Mazati, she had by now understood that Roman Catholicism was the true religion, and in her heart she had already converted. She was also pregnant, and gave birth to a child, who died soon thereafter. She thus knocked on the door of a convent, went to confession, was hidden by the nuns, and began to write her memories.

In the convent worked, however, a strange gardener, who was probably an agent of the Seventh Circle. This was where the first French edition of the novel ended, while in the second edition a sinister piece of information was included: “Bersone was kidnapped from the convent, where she was working as a receptionist, by the false gardener. He took her to a Satanist lodge, where she was crucified.” It is not clear when this macabre detail was included and whether it was found at the end of the “manuscript” signed by Clotilde Bersone—admitting such a manuscript ever existed.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.