That Shambhala can be established on earth was an idea Roerich was able to sell to Stalin. But the dictator and the artist had in mind different kinds of kingdoms.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 2 of 3. Read article 1.

Scene 3: Moscow

[scenes 1 and 2 take place in Tibet and Paris: please refer to article 1 of this series]

Russia, in the early 20th century, witnessed the birth of new great politico-religious utopias. Anti-Western aristocrats such as Prince Esper Uhtomskij (1861–1921) converted to Buddhism and proclaimed that Russia could affirm his superiority over the materialistic West only by building a Buddhist empire. It would include Tibet, Mongolia, and China, and prepare the advent of the millenarian kingdom of Shambhala.

Through Uhtomskij and others, Buryat Buddhist leaders such as Agvan Dorzhiev (1854–1938) met with Czar Nicholas II (1894–1917), hinting at the fact that they represented mysterious Asian brotherhoods and perhaps the Masters themselves. They endorsed the legend that the Romanov Czars were descendants of the Kings of Shambhala, and urged them to recreate a Shambhala on earth.

The Czar, who was a good Orthodox Christian, did not take these proposals very seriously. Dorzhiev was among those who believed, after 1917, that the plan for Shambhala may be realized by the Bolsheviks. For a while, he even promoted a cult of Lenin (1870–1924) among Mongol and Buryat Buddhists.

Soviet biologist and occultist Alexander Barchenko (1881–1938) was among those who researched the physical location of Shambhala and Agartha. Interested in the subject for a while, Stalin (1878–1953) finally lost patience with these theories and had both Lama Dorzhiev and Barchenko executed (or killed in jail) in 1938.

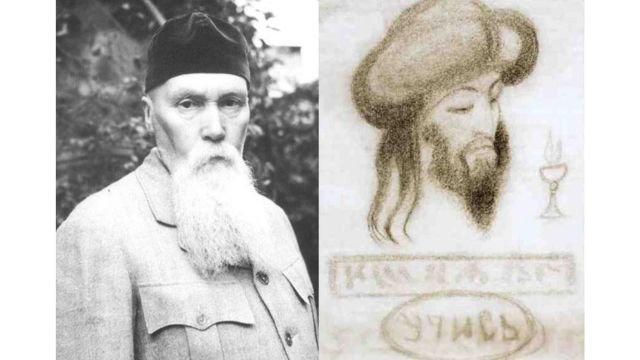

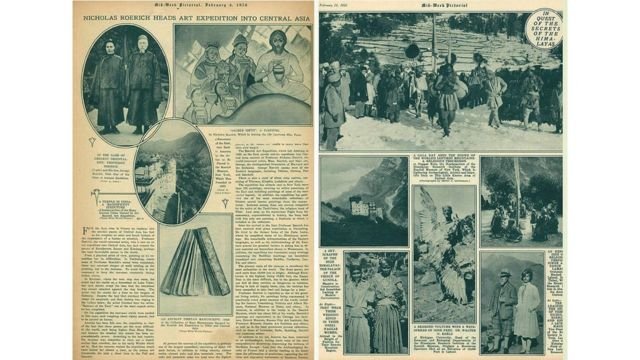

However, there was somebody the Soviets respected more, and who had very similar ideas. Russian painter Nicholas Roerich, together with his wife Helena (1879–1955), had been receiving for years messages from the two main Masters who had spoken to Madame Blavatsky, Koot Hoomi and Morya. He even claimed he had seen them in person in Hyde Park in London in 1920.

The messages were rejected by the Theosophical Society, which led the Roerichs to establish their own Theosophical organization, Agni Yoga, which is still in existence to this day.

Roerich had met Dorzhiev in 1909, when both were involved in the construction of the Buddhist Tantric temple of Saint Petersburg, and heard from him tales of Agartha and Shambhala. By then, at age 35, Roerich was already recognized as one of Russia’s greatest artists.

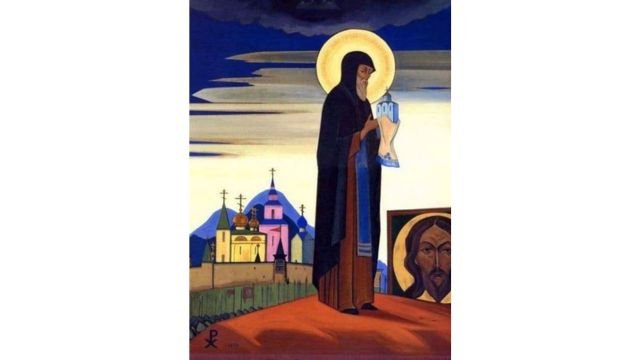

Roerich repeatedly portrayed the Russian saint Sergius of Radonezh (1314–1392), whom he regarded as an incarnation of Master Morya. Saint Sergius played an important part on Roerich’s mysticism of Russia, which he saw as the quintessentially spiritual nation, called to ally herself with the Masters, unite with China, Tibet, and Mongolia, and realize Shambhala, the earthly paradise.

In the last few years, the opening of the Soviet archives, several Ph.D. dissertations on the Roerichs, the availability of Helena’s diaries, and the publication of the journals of Sina Fosdick (1889–1983), Roerich’s close associate and successor as leader of Agni Yoga, have revolutionized our understanding of the painter and his wife. It is now clear that Nicholas received from the Masters, particularly Allal Ming (i.e. Morya), messages not less important than his wife’s, which directed him to establish a millennial kingdom in Central Asia.

Until 1921, Allal Ming told Roerich that the Bolsheviks would not last. Later, however, he changed his mind, and revealed that Lenin had been an emissary of the Masters. He directed Roerich to contact the Soviet authorities and propose to them a “Buddho-Communist” utopia. The Bolsheviks understood it as a great federation of Communist republics from Poland to China, but for Roerich it was in fact the gateway to the earthly paradise of Shambhala.

Roerich also believed that huge subterranean areas in Central Asia were, in fact, Agartha. Archival documents reveal that he was taken very seriously by prominent Soviet leaders such as Commissar for Trade Leonid Krasin (1870–1926), Foreign Minister Georgy Chicherin (1872–1936), and Stalin himself. Through Roerich, both Chicherin and Stalin received messages from the Masters.

The Soviets helped the Roerichs in their Asian expeditions in 1925–1929. Stalin believed that Roerich would promote the Russian interests in a crucial strategic area. The Roerichs, however, were looking for the Masters, Shambhala, and the establishment of a millenarian kingdom centered on the Altai mountains.

The ruler of this kingdom was not to be Stalin, but Roerich himself. The Masters revealed to Nicholas that he was the reincarnation of the 5th Dalai Lama (1617–1682), a key figure in the political history of Tibet, and the claim was endorsed by some Tibetan monks. Although this is disputed, scholars such as French historian Dany Savelli suggest that during his 1925 trip to Kashmir and Ladakh, Roerich also identified himself with the Buddha Maitreya and a returning King Gesar of Ling.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.