The notions of mythical and mystical kingdoms Shambhala and Agartha, as we know them today, are largely influenced by the views of the Russian painter.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 1 of 3.

We are down-to-earth Westerners, aren’t we? We leave to Asia, or to a past we believe the Enlightenment liberated us from, ideas of mysterious inaccessible lands where milk and honey flow, peace reigns, and all inhabitants have extraordinary abilities. Yet, many Western new religious movements also have teachings about earthly paradises, and not all derive from the Bible.

I would argue that this is largely due to the multiple (if neglected) influences of Western esotericism, and that a key figure in this respect is Russian painter Nicholas Roerich (1874–1947). To illustrate this thesis, we will travel to different parts of the world in the three parts of this series of articles.

Scene 1 – Tibet

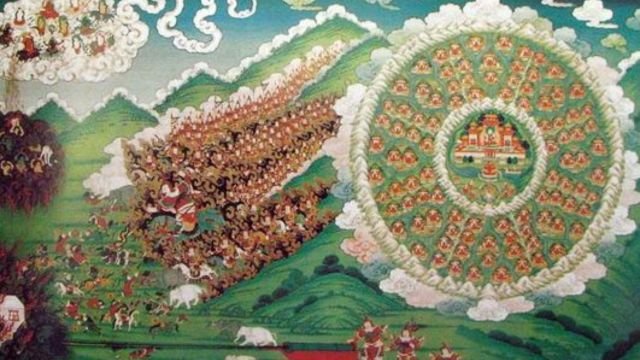

Two notions often confused should be disentangled, Shambhala (the common spelling derived from Tibetan of the Sanskrit “Sambhala”) and Agartha. Shambhala is mentioned in the “Kalachakra Tantra” (early 11th century) as a mythical kingdom whose existence is physical, yet at the border with the metaphysical.

The “Kalachakra Tantra” includes a millennial prophecy: the king of Shambhala will come again, and fight a final battle for the triumph of righteousness and Buddhism, ushering in an earthly paradise.

The future manifestation of Shambhala is connected with two distinct sets of prophecies: about a latter-day kingdom of the Maitreya Buddha and about the return of the mythical King Gesar of Ling, which according to Tibetan, Mongolian, and other traditions was a legendary hero and ruler of the early Middle Ages.

Scene 2: The Hollow Earth—or Paris

Unlike Shambhala, the concept of Agartha is not traditional. We find it in Paris, used first by French occult novelist Louis Jacolliot (1837–1890) in 1873, more or less as a synonym of Shambhala. It became popular in Western esotericism in 1910, when the book “Mission de l’Inde,” by Alexandre Saint-Yves d’Alveydre (1842–1909), originally written around 1886, was published, one year after the death of his author.

Saint-Yves claimed that Agartha was actually a physical place, only it existed underground, under the mountains of Asia. It was the residence of the Master of the Universe and of the most advanced civilization of our world.

Saint-Yves combined two different narratives. That Masters hidden somewhere between India and Tibet wielded great power had been taught by Madame Helena Blavatsky (1831–1891) and her Theosophical Society. That a hollow Earth harbored an underground high-level spiritual center had been suggested in Britain, before Saint-Yves, by novelist and politician Edward Bulwer-Lytton (1803–1873) in “The Coming Race” (1871) and by medium and Theosophist Emma Hardinge Britten (1823–1899) in “Ghost Land” (1876).

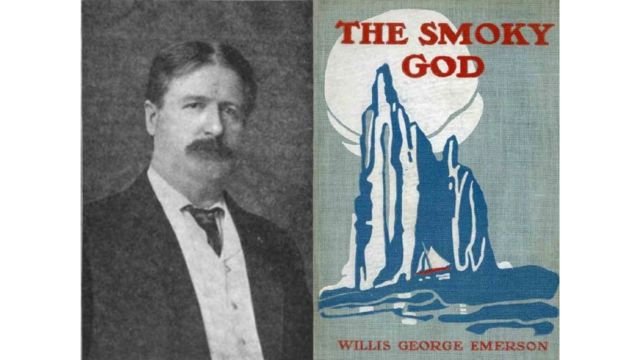

But was all this symbol, metaphor, or reality? Among the first to claim that it was absolutely real was Chicago lawyer and businessman Willis George Emerson (1856–1918). In 1908, he published “The Smoky God,” allegedly an account written by a Norwegian sailor, Olaf Jansen, who had found near the North Pole the entrance to a subterranean kingdom, whose capital was the original Garden of Eden. Occultists quickly claimed Jansen had found Agartha.

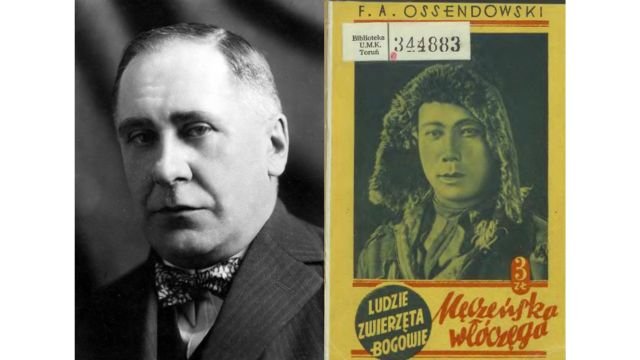

Much more seriously was taken Polish (although born in present-day Latvia) explorer Ferdynand Ossendowski (1876–1945). He had traveled to Central and Eastern Asia and had played an ambiguous role in the political game between Russia, China, and the West to control the three strategically crucial areas of Tibet, Mongolia, and present-day Xinjiang.

In 1922, Ossendowski published “Beasts, Men and Gods.” He claimed to have collected evidence about the underground kingdom of Agartha, where the King of the World reigned. He also mentioned a prophecy that, as human corruption will increase, “the peoples of Agartha will come up from their subterranean caverns to the surface of the earth” to establish a righteous kingdom.

We are still in Paris, though. There, on July 26, 1924, the editor of the prestigious “Nouvelles Littéraires,” Frédéric Lefèvre (1889–1949), invited Catholic philosopher Jacques Maritain (1882–1973), historian of Asia René Grousset (1885–1952), and esoteric author René Guénon (1886–1951) to debate Ossendowski, who was visiting France.

Grousset and Maritain remained skeptical, but Guénon found in Ossendowski, together with “unbelievable” tales and passages simply derived from Saint-Yves and others, original and valuable information. The debate influenced Guénon’s decision to publish in 1927 “Le Roi du monde” (whose first part appeared in December 1924 in the Italian esoteric journal “Atanòr”), where he discussed the theory of a “King of the World” and of hidden spiritual centers located in Asia.

A plethora of secret societies mentioned Agartha and Shambhala. Their leaders were not necessarily experts of Asian religion and legends, and often confused the two notions. For a certain Western practical mentality, the main question was whether Shambhala or Agartha would come out from wherever secret place they were and really establish an earthly paradise, which would also imply dealing with the current political circumstances. This question will generate a special interest in Russia and the United States, as we will see in the next articles of this series.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.