Lê Phô, Mai Thứ, and Vũ Cao Đàm lived in France and learned French artistic techniques but never forgot the Buddhas and spirits of Vietnam’s tradition.

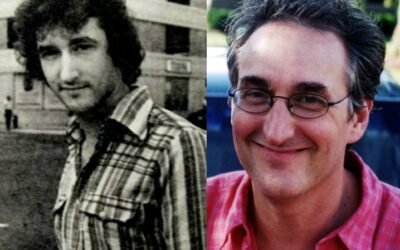

Massimo Introvigne

Until March 9, Paris’ Musée Cernuschi offers a beautiful exhibition of three modern Vietnamese painters who lived for many years in France: Lê Phô (1907–2001), Mai Thứ (1906–1980), and Vũ Cao Đàm (1908–2000). I should confess that not only I am not an expert of the trio. I had no idea who they were, until my colleague Bernadette Rigal-Cellard, who is in love with all things Vietnamese, persuaded my wife and me to accompany her to see the exhibition.

To be even more honest, I didn’t even know that a Vietnamese modern art had existed before the most recent abstract and postmodernist experiments I had seen in Vietnam. The exhibition explains it was largely a French enterprise. French colonialism created in Hanoi in 1925 the Indochina School of Fine Arts, directed by Victor Tardieu. The most gifted pupils received scholarships to go to France, including the three featured in the Cernuschi exhibition. They went to France in the 1930s and spent most of the rest of their life there.

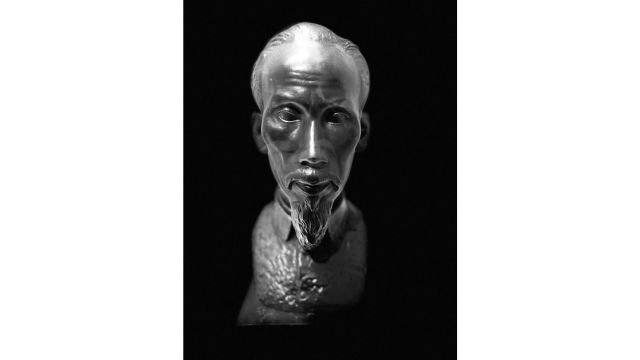

They kept a continuous conversation with Vietnam, though. When Hồ Chí Minh as President of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, visited Paris in 1946, Vũ Cao Đàm sculpted his bust, who was never exhibited and was even hidden for many years due to the deterioration of the relationships between Hồ and France. Mai Thứ, who was also a filmmaker, made a short film about the visit.

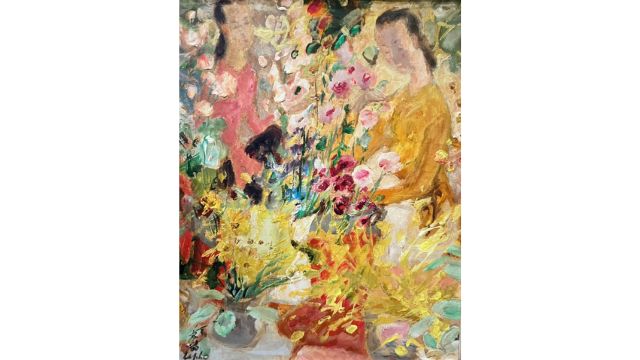

The strength of the Cernuschi exhibition is to show that, having been formed by French academic artists and spent most of their life in France, the three artists remained distinctly Vietnamese. Unlike most of their contemporary Chinese modernists, their art remained rooted in the multiple religious traditions of Vietnam. One of Vũ Cao Đàm’s masterpieces is a Buddha he sculpted in 1933.

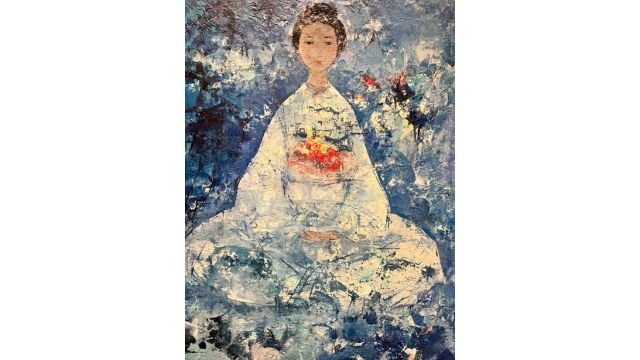

Much later, in 1961, when he was living in Saint-Paul-de-Vence, not far from Chagall’s residence, he painted an extraordinary “Divinity,” which is at the same time Buddha, the bodhisattva of compassion Guanyin, and a universal divine figure.

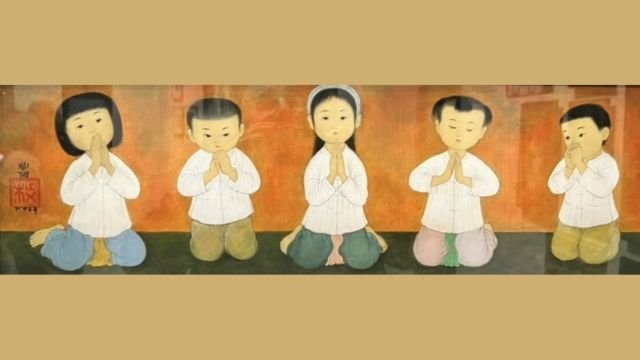

Both Vũ Cao Đàm and Mai Thứ painted on silk scenes of prayer, drawing on both the Buddhist and the Catholic heritage of modern Vietnam.

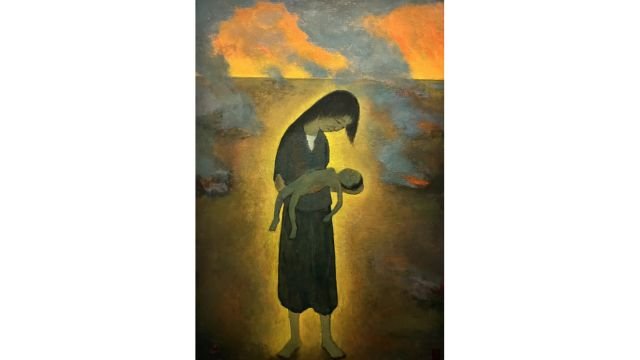

“Desolation,” painted by Mai Thứ in 1966 to represent the horrors of the Vietnam War, is also a deeply religious painting, reminiscent of Buddhist and Christian representations of Hiroshima after the bombing by Japanese artists.

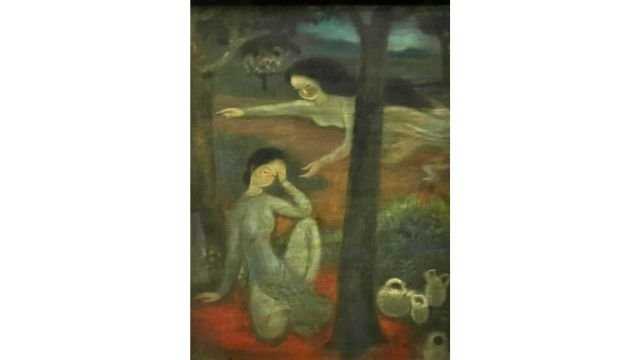

All three artists produced works inspired by the epic novel “The Tale of Kiều” by Nguyễn Du (1765–1820), which are largely featured in the Paris exhibition. Apart from its discussion of prostitution, the “Tale” is full of folk religiosity and spirits. In Vũ Cao Đàm’s “The Dream” (1952), we see the spirit of a deceased prostitute appearing to Kiều.

The very Chagallian “Composition” (1959) also by Vũ Cao Đàm, shows a tomb-sweeping ritual performed by Kiều and her sister Vân, when Kiều’ love, Kim, arrives on horseback. The whole novel is full of Buddhist vows, divinations, and spirits. While honoring Hồ Chí Minh, and being honored in turn by postwar Communist Vietnam, the three Vietnamese artists in France never lost touch with a culture imbued with supernatural elements.

The two things are not contradictory. As the young Vietnamese scholar Thien-Huong Ninh has demonstrated, there are several new religious movements in Vietnam today where the spirit of Hồ Chí Minh regularly appears. Expelling the spirits from Vietnam has proved more difficult than expelling the French and the Americans.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.