The theme of the androgyne has a long history in Western culture and came to Ferenzona through the Rosicrucians and the Theosophical Society.

by Massimo Introvigne*

*Conference part of the cultural calendar “ATANÒR: La Metamorfosi delle Forze,” in connection with the exhibition “Raoul Dal Molin Ferenzona: Enchiridion Notturno. Un sognatore decadente verso l’occultismo e la teosofia,” promoted and organized by the Municipality of Collesalvetti, conceived and curated by Emanuele Bardazzi and Francesca Cagianelli, with the contribution of Fondazione Livorno, in collaboration with the Italian Theosophical Society; Pinacoteca Comunale Carlo Servolini, Collesalvetti, January 11, 2025.

In the award-winning film starring Italian comedians Aldo Giovanni and Giacomo “Three Men and a Leg” (1997), Chiara tells her three friends about the myth of the androgyne as Plato has it expounded by Aristophanes in the “Symposium.” According to the myth, in the beginning there were three kinds of human beings, not just two: the female, born of the Earth; the male, born of the Sun; and the androgyne, born of the Moon, a being “composed of the first two and containing both.” Androgynes were round beings with two faces (on either side of the same head), four arms, four legs, and two genitalia. They reproduced without sexuality.

Having provoked the wrath of the gods by trying to equal them, the androgynes were punished by Zeus, who divided them into two halves. Humanity thus fragmented into two species, men and women. Each new being then sought its former half to reconstitute the original androgyne. But this proved impossible, and men and women died of starvation and despair. To prevent the extinction of the human race, Zeus moved the genitals to the front, allowing men and women to unite, forming the humans of today.

Originally to the Greeks and Romans the birth of children with both sexual characters was considered a new curse of Zeus. The children were immediately killed and the city where they were born purified with a ritual procession. Thus the birth of a hermaphrodite child in Sinuessa during the Second Punic War was interpreted as an omen of defeat and the child was immediately put to death.

Perfect love was considered the reunion of the two halves and the new formation of the androgyne. This is one of the meanings of the fable of Cupid and Psyche in Apuleius’ work “The Metamorphoses,” which dates back to the second century CE. Envied by Venus for her beauty, and able to make the god of love himself, Eros, fall in love with her, Psyche (whose name evokes the soul and knowledge) must go through several trials, including a visit to the realm of the dead and a seemingly eternal sleep from which Eros awakens her. She can thus finally achieve union with her beloved, which is also the restoration of the perfect androgyne.

The story of Cupid and Psyche has never disappeared from the Western imagination and has had countless incarnations. We find it again, for example, in the fairy tale of Sleeping Beauty, which itself had a long genesis and tells us of the trials —including, again, a seemingly invincible sleep —that must be overcome to arrive at perfect love.

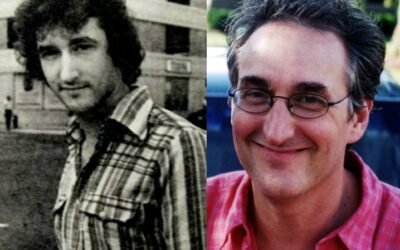

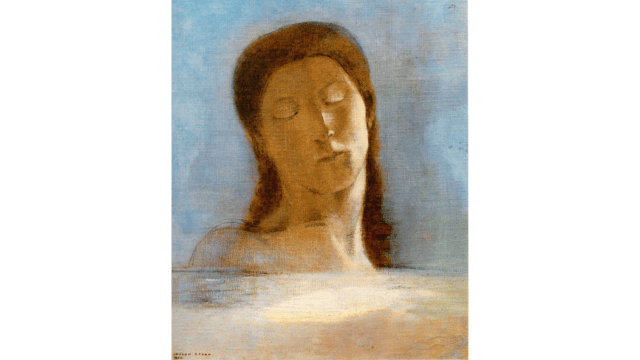

The image of Sleeping Beauty reproduced above is by Hermann Schmiechen, a Bavarian painter and member of the Theosophical Society famous for having put on canvas in 1884, while receiving them telepathically from Madame Blavatsky through the mediation of another Theosophist, Laura Holloway, the most famous images of two of the Masters of Theosophy, Morya and Koot Hoomi. The Masters are not deities but superior human beings who have decided to remain in the world, hidden in inaccessible places, to help humankind, even though they have completed the cycle of reincarnations. According to Blavatsky, the Masters have achieved the state of androgyny, an original perfection that humanity will regain with the coming advent of the sixth “root race.”

Ferenzona was familiar with the subject of androgyny from his encounters with the Theosophical Society and its Roman schism gathered around Decio Calvari but before that from his European travels. Since the first decade of the 20th century, they had brought him into contact with the circles of the Salons de la Rose+Croix whose founder, Joséphin Péladan, had published the novel “L’androgyne” in 1890.

Péladan thought the most perfect representation of the androgyne was that of the Greek sculptor Polycles, whose Roman copy of a lost original “Sleeping Hermaphrodite” he could admire in the Louvre, embellished with a marble bed created in the 17th century, when the sculpture was found in Rome, by Gian Lorenzo Bernini.

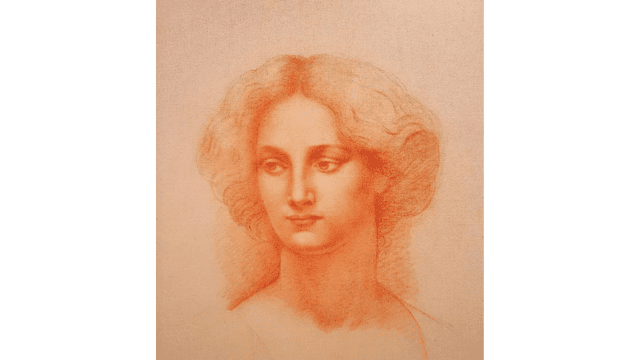

Some illustrations for “L’androgyne” were prepared by an artist from Péladan’s circle, Alexandre Séon. Péladan had also commissioned him to draft an illustration for the title page of his novel “Curieuse!” (1886), which depicts the Platonic love of Nebo and Paula. The drawing, which the publisher later decided not to use, is significant for the issue of androgyny because it does not represent Paula, or even Nebo, but the androgynous being who is the result of the perfect fusion of the two lovers.

Another “Androgyne,” of which only the preparatory drawing remains today, was exhibited at the 1896 Salon de la Rose-Croix by Armand Point. This is an environment that, as Michele Olzi showed, Ferenzona knew well and by which he was profoundly influenced.

One cannot help but evoke here also Odilon Redon, who was close to Séon, and who in turn created an unforgettable androgynous figure in the various versions of his “Les yeux clos” of the years 1889–90, which became true icons of the Symbolist movement.

All these artists read Honoré de Balzac, who inspired by the writings of the Swedish esotericist and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg had published in 1834 the novel “Séraphîta.” It was perhaps the most famous literary depiction of a mysterious androgynous being, who is both male (Séraphîtüs) and female (Séraphîta), with parallel lives and loves. It is a condition he cannot resolve in our imperfect world, so that he eventually turns into an angel and ascends to Heaven.

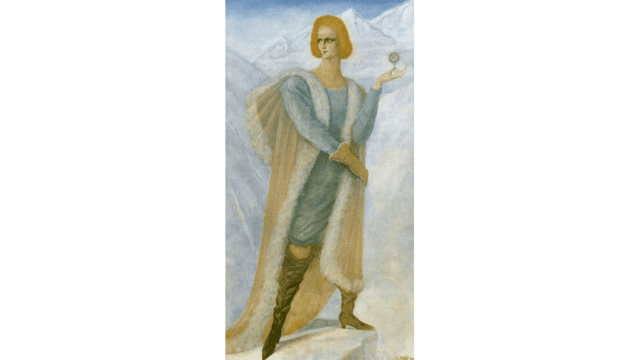

The most important pictorial depiction of Séraphîta is the 1932 work by Belgian artist Jean Delville, who was the founder and leader of the Theosophical Society in his country. Ferenzona had known Delville since 1906, and in the following decade he became involved with the Theosophical Society.

Among the European leaders of the Theosophical Society, Delville was one of the closest to Jiddu Krishnamurti, the young Indian raised from childhood by Theosophists to one day become the World Teacher. When Krishnamurti announced in 1929 that he did not intend to assume this role but to pursue a spiritual path independent of the Theosophical Society, Delville entered a period of deep spiritual crisis.

Emanuele Bardazzi believes that a portrait Ferenzona painted in 1930 may represent Krishnamurti, whom the artist might have met during the Indian master’s visit to Italy in 1929. Bardazzi thinks Ferenzona may have been inspired by a portrait of Krishnamurti (the only one where he appears wearing a turban) by the Spanish-Costa Rican painter Tomás Povedano de Arcos, himself a Theosophical leader, which had been reproduced in Italy in “Repertorio Americano” in 1929.

Crucial to these interests are Ferenzona’s passages to Rome, where he met future esoteric luminaries such as Julius Evola and probably Giuliano Kremmerz, or at least the circle of his Roman followers. In 1917 Ferenzona exhibited in Rome at the headquarters of a splinter group of the Theosophical Society, the Theosophical League led by Decio Calvari.

With Evola, Ferenzona participated in the “Cenacolo d’arte dell’Augusteo” animated by Arturo Ciacelli. In 1919, he held an “Esoteric Course in Art History and Spiritual Science” and began a correspondence with composer and anthroposophist Lamberto Caffarelli on the possible founding of a new Rosicrucian society in Italy.

Although from the late 1910s Ferenzona went through a series of spiritual and personal crises and rapprochements with Catholicism, his self-identification with the Rosy Cross was confirmed by his works “Zodiacal – Religious Opera” (1919) “AôB – Enchiridion Notturno. Twelve nomadic mirages, twelve original spikes. Rosicrucian Mysteries No. 2” (1923) and ”Ave Maria! Rosicrucian Mysteries (Opera 6.a)” (the last two titles also allude to the music of Fryderyk Chopin).

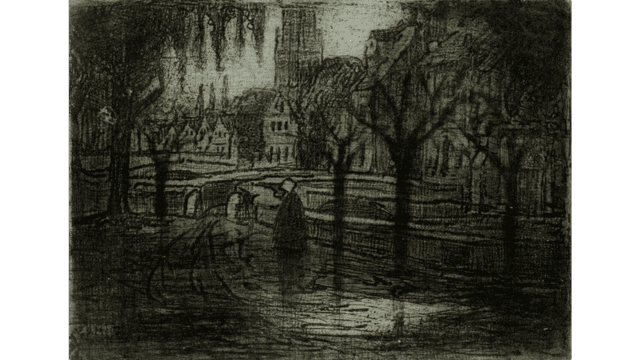

Like other artists, Ferenzona finds commonality between the particular atmosphere of Bruges described in Georges Rodenbach’s novel “Bruges-la-Morte” (1892) and the Italian city of Orvieto. Ferenzona also traveled to Central Europe and was influenced by Czech symbolist Josef Váchal, yet another member of the Theosophical Society.

Mentioning Váchal immediately raises the question of Ferenzona’s fascination with angels and demons, as both appear in the Czech artist and Theosophist’s output. Ferenzona was a kindred spirit. Some of his women are not only witches and “belles dames sans merci,” but present the characteristics of she-demons. On the other hand, Ferenzona’s is also an art of angels and ultimately a form of Christian esotericism.

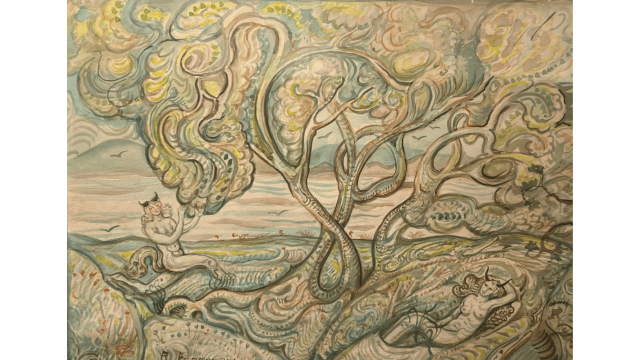

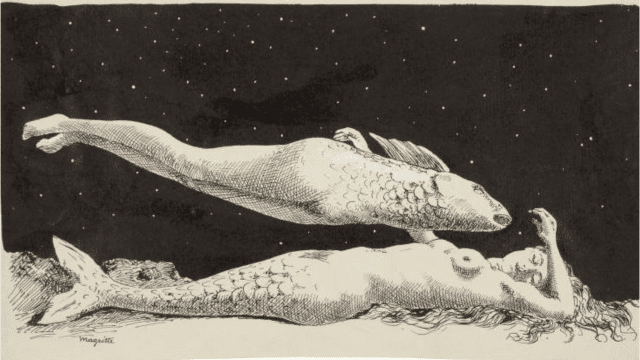

Returning to the androgyne, one should not assume that, once the season of symbolism was over, it disappeared from art history. In the Surrealist milieu, both André Breton and André Masson continued to write about the theme. At an unspecified date in the 1930s, René Magritte drew “The Dream of the Androgyne.”

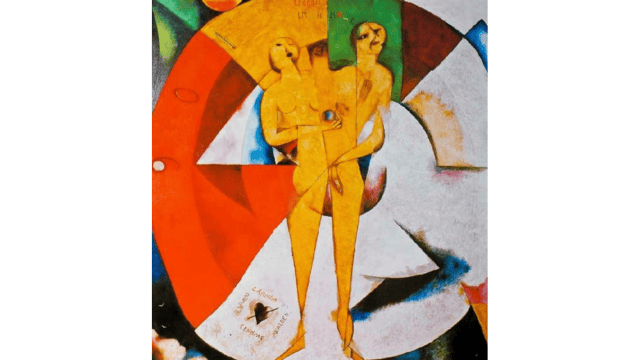

Worthy of concluding a review on the androgyne is Marc Chagall’s 1911–12 painting “Hommage à Apollinaire.” We understand from the apple the female figure holds that Adam and Eve are depicted, but in their original androgynous unity before the Fall.

The theme is central to Jewish Kabbalah, which Chagall was familiar with. But it is also an eternal theme for artists and literati reflecting on life—and love.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.