An exhibition in Kaunas lifts the veil on an important painter and opera set designer, who managed to hide in his works symbols the censors did not understand.

by Massimo Introvigne

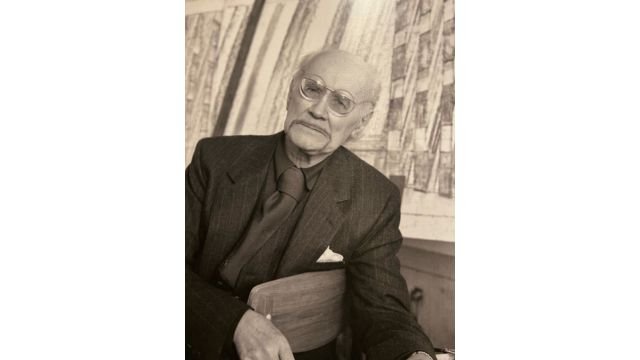

St. Nicholas Church in Kaunas, Lithuania, once hosted a large triptych depicting the Twelve Apostles, regarded as the masterpiece of Lithuanian painter Liudas Truikys (1904–1987). The Soviets converted the church into a library storage facility in 1948. The triptych disappeared and was believed to be lost. However, in 2023, it was almost miraculously discovered, hidden in an attic above the church.

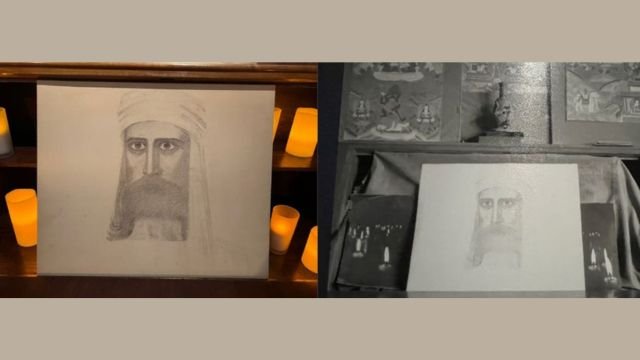

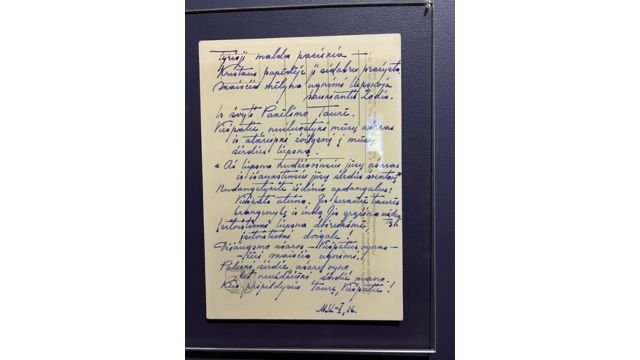

This discovery offered the opportunity for the exhibition “Liudas Truikys: Art Is a Sacrifice to the Cosmic Balance,” which opened at Kaunas’ Čiurlionis Museum on October 18 and runs through February 16, 2025. It should not be missed by those interested in the relationships between art and Theosophy. Just like Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis (1875–1911), from whom he was greatly influenced, Truikys was (probably) not a card-carrying member of the Theosophical Society. However, he was Theosophist enough to have an altar dedicated to Master Morya in the home he shared in Kaunas with his partner, soprano Marijona Rakauskaitė (1892–1975), and his correspondence reveals his deep Theosophical interests.

Truikys was born in 1904 in Pagilaičiai, near Plungė, from a deeply Catholic father and a mother who, if we believe the artist’s lather recollections, practiced discreet rituals honoring pre-Christian Lithuanian deities. He was sent to the Telšiai Gymnasium, where he met philosopher Vydūnas (Wilhelm Storost, 1868–1953), who occasionally taught there. Vydūnas was both a Theosophist and a pioneer of the neo-Pagan revival in Lithuania. Later, at the Kaunas Art School, while he was already immersed in the study of Theosophical texts, Truikys came to know the art and esoteric ideas of Nicholas Roerich (1874–1947), another crucial influence on his life and artistic production.

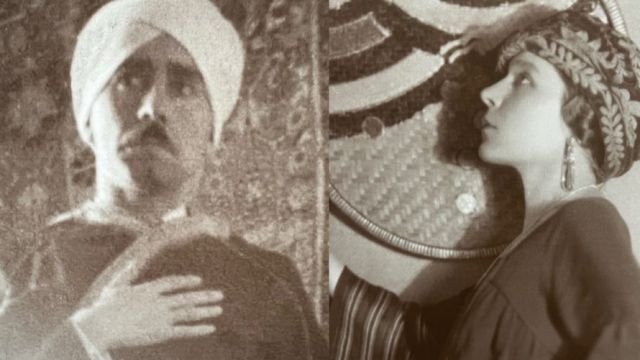

Both Truikys and Marijona Rakauskaitė attended the meetings of the Lithuanian Roerich Society in the period between the two World Wars. It was from Roerich that they accepted the key role of Master Morya, whom they regarded as their spiritual guide.

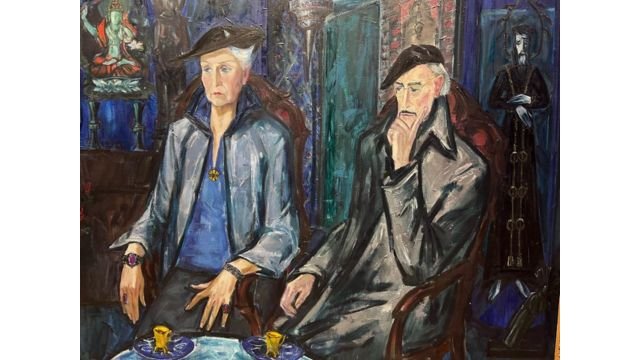

A painter and noted collector of Asian art, Truikys became mostly known for his work in Catholic churches, where the influence of Roerich remains visible, and his sceneries and costumes for operas and ballets. He came to be acknowledged as the undisputed master in Lithuania of this peculiar kind of art. He privileged the Italian composers such as Giuseppe Verdi (1813–1901) and Giacomo Puccini (1858–1924). However, in the interwar period, he also worked with enthusiasm for operas by Lithuanian composers on pre-Christian or nationalist themes. There, he often included Asian symbols and references combined with pre-Christian Lithuanian features, as both Vydūnas and Čiurlionis had done in their own ways.

All this became dangerous in Soviet times. Truikys continued to spread privately among his friends ideas and literature of the Theosophical Society, which was banned in the Soviet Union. Although he was widely respected for his opera sceneries and costumes, he lost his position at the Vilnius Opera and Ballet Theater as his art was regarded as incompatible with socialism realism. After Stalin’s death, however, Communist authorities in Lithuania realized that there was simply nobody in the republic who could work with opera productions and guarantee the quality of Truikys. He was called back to his position and was even allowed to paint new frescoes in some Catholic churches.

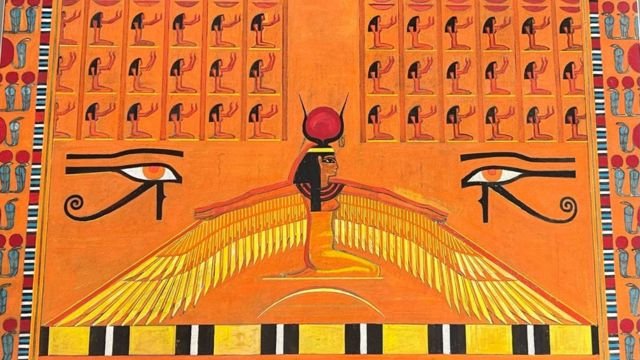

As the Kaunas exhibition demonstrates, Truikys remained both a Theosophist and a Lithuanian nationalist but hid these themes in his work for the operas so that the Soviet censors would not recognize them (but many in the Lithuanian audiences did). Verdi’s “Aida,” and Puccini’s “Madama Butterfly” might have depicted faux, orientalist Egypt and Japan, but Truikys read the librettos through Theosophical lenses and his superior knowledge of both ancient Egyptian and Asian religions.

He also included the motif of the Great Triad as the key to his scenery for Puccini’s “Turandot,” although in the end the opera was not represented.

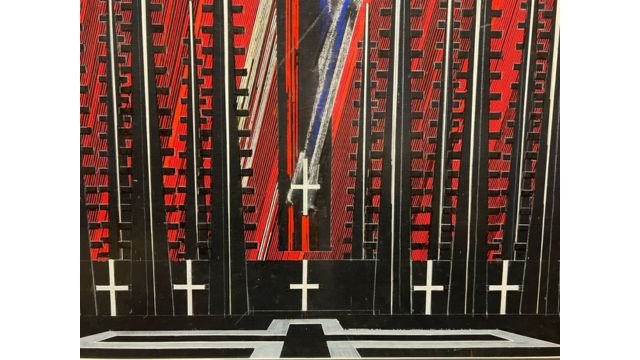

In 1968, the Soviet authorities allowed again a representation in Kaunas of the opera “Gražina,” by Jurgis Karnavičius (1884–1941) and Kazys Inčiūra (1906–1974), the first national opera created in independent Lithuania, which had originally premiered in 1933. It depicts the battles between Pagan Lithuanians and Teutonic crusaders. As the Kaunas exhibition shows, Truikys consciously made the scenery into a metaphor of the conflict between the Soviets and those who dreamed of an independent Lithuania, although censors again failed to see it.

In 1975, the death of his beloved Marijona Rakauskaitė inaugurated a period of depression and crisis for Truikys. He came out of it after Marijona appeared to him in a dream, offering to the artists the fire and the “Requiem,” a new symbol in the shape of a light-colored cross, which will become ubiquitous in Truikys’ productions of the 1980s. In 1981, he returned to an opera he had worked for before, Verdi’s “Don Carlos,” and moved its scene from the secular Escorial Palace to what he called “a Gothic medieval crypt, the site of spiritual retreats.” He elaborated on the hidden meanings of Gothic art revealed by esoteric and Theosophical literature, certainly going beyond Verdi’s intentions.

Truikys died in 1987, still in Soviet Lithuania. Independence was not far away. The artist did work with official Soviet institutions. Yet, he managed to navigate through the fastidious but not particularly bright Soviet censorship and to kept alive the flame of a sacred Lithuanian art and of Theosophy, waiting for better times to come.

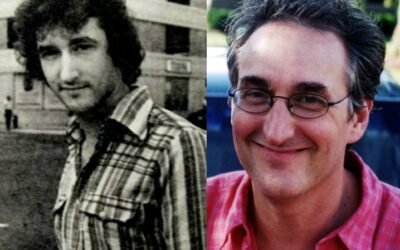

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.