Harris denied that his art “preached” Theosophy through symbols. It was “Theosophical” in the sense of being a divine experience of essential forms.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 5 of 5. Read article 1, article 2, article 3, and article 4.

Harris expanded on his thoughts about art and Theosophy in an unpublished and undated manuscript titled “Abstract Art.” According to Harris, the human “races” progress through artistic expression. What type of art? Not the mere “imitation of anything in visible nature,” which is “nothing less than a prostitution of great powers.” The artistic creative force should transition from the natural world to the realm of art, though not via symbols.

Harris emphasized that symbols hold significant value in Theosophy. “Theosophical Symbols contain the whole of the Philosophy.” Symbols “always refer to something—point to some quality or idea in man or the universe or in nature that is not actually in the symbol—Now the contrary is true of a work of art.” “Any symbol introduced into the work of art, if that symbol refers to something outside of the work tends to destroy or vitiate the unique experience a work of art embodies.”

Harris’ art intentionally avoids the use of symbols. He believed that symbols draw the viewer away from the artwork, and he wanted his audience to fully immerse themselves in his paintings, experiencing a sense of unity with them. While Harris attributed this idea to Blavatsky, the influence of Christian Science is also clear. He viewed the use of symbols to influence others as a form of “animal magnetism,” which is a dangerous evil for a Christian Scientist.

Harris regarded music as the only art form free from symbols, but he acknowledged that most significant religious and spiritual art has been symbolic. By adopting Blavatsky’s evolutionary perspective on history, he argued that modernity was so distinct from previous eras that it necessitated a new (post-symbolic) art form. He claimed that symbolic art was fitting for an earlier time when ideals like sainthood were represented by “beautiful halos.”

Modern art should enable us to “experience within ourselves a touch of saintliness” without using halos. Ultimately, Harris contended that Theosophy enabled a genuinely modernist aesthetic, freeing artists from relying on symbols. He forcefully argued that a non-symbolic aesthetic could be drawn from Blavatsky, although the co-founder of the Theosophical Society had encouraged a symbolist and instructional art form.

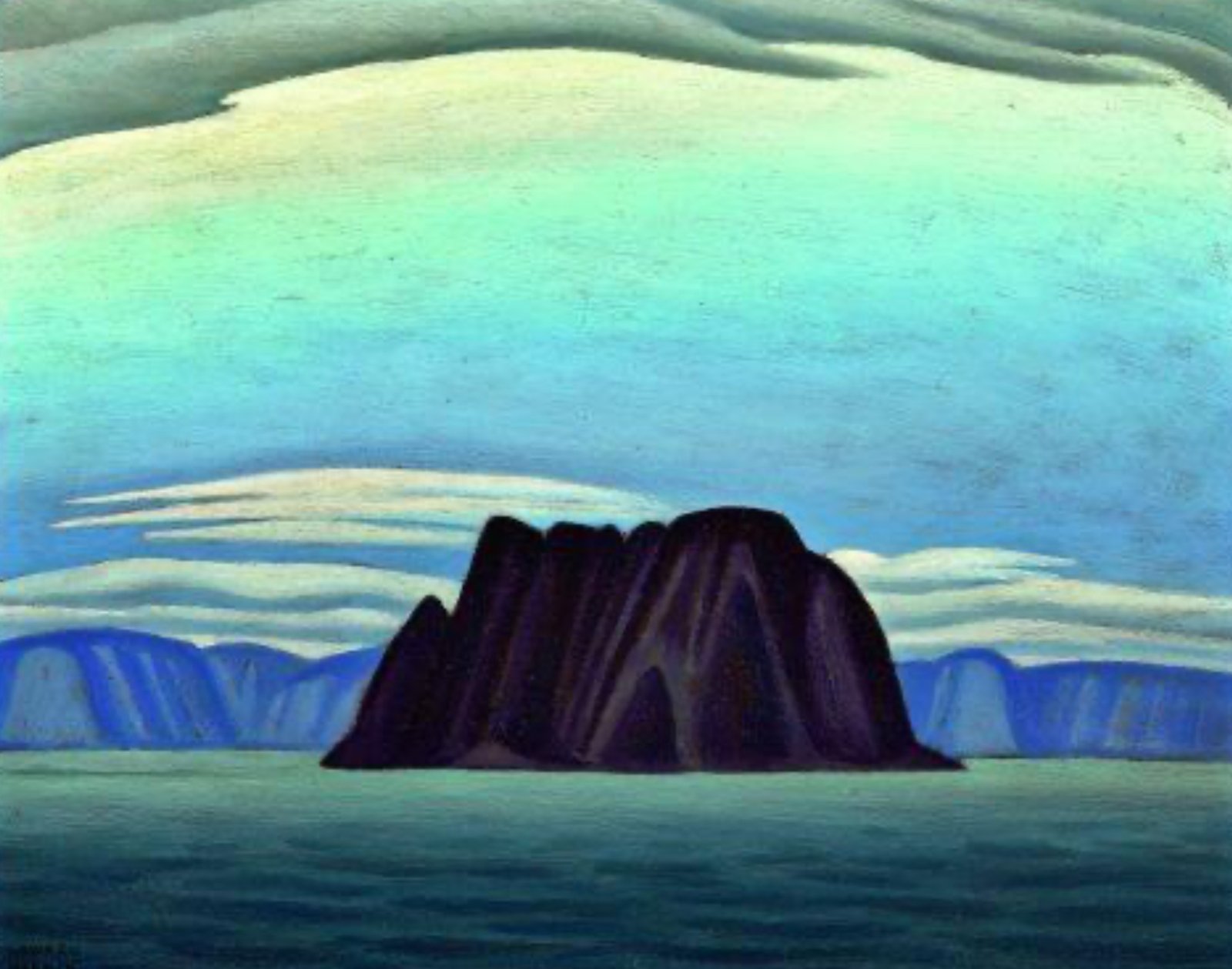

The rejection of symbolism is vital for understanding Harris. The early researchers who acknowledged the substantial impact of Theosophy on Harris and the artists in his circle found Theosophical symbols in a range of his works. Notable among these scholars are Ann Davis, Father Peter Daniel Larisey, a Jesuit scholar (1928–2020), and Dennis Reid, who analyzed Harris’ later abstract pieces, where identifying symbols becomes more difficult. However, Harris had already dismissed this interpretation of his artworks: “A recent writer stated that in the Lake Superior, mountain, and Arctic paintings, I imposed forms on nature. I can understand the statement, but I am sure it is not true. I was so far as I know moved by the shapes and forms themselves to eliminate all irrelevant details in an endeavor to make essential forms.” Again, the idea of reducing forms to their essential elements can be found in Blavatsky, although it was not necessarily understood by the artists she worked with, such as Heinrich Schmiechen (1855–1925) or Reginald Machell (1854–1927), as it would later be by Harris or Piet Mondrian (1872–1944).

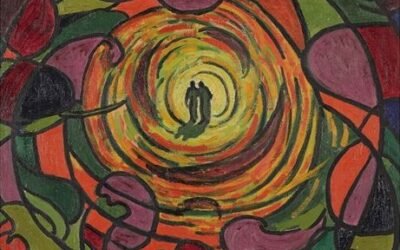

For artists, exceptions exist to every rule. In 1960, at the age of 75, while primarily creating untitled abstractions, Harris produced what many critics consider the finest piece of his later work. Entitled “Atma Buddhi Manas,” it reflects Harris’ 1960s style and is reminiscent of diagrams found in early Theosophical literature. The painting illustrates three forms suspended in an energetic ocean. Atma, the undifferentiated absolute, descends from above into buddhi, which occupies the center as the first differentiation. Below lies manas, representing the consciousness of our current existence. The diagram can also be interpreted from bottom to top: after achieving manas as a higher intellectual state, one may strive to reach buddhi, a more elevated level of spiritual awareness, and gain a glimpse of atma, which transcends consciousness. This painting is important as it demonstrates Harris’ continued dedication to Blavatsky’s ideas in 1960. It also implies that we should consider the artist’s strong dismissal of symbols and symbolism with a grain of salt.

This prompts an inquiry into whether, and how, Harris’ art can be defined as “Theosophical.” In a letter approved by her husband, his second wife, Bess, wrote, in 1968, to art historian Dennis Reid that the artist never intended to “paint the ‘dogmas and doctrines’ of the Theosophical Society.”

At first glance, this might appear to be at odds with Harris’ extensive theoretical work regarding the connection between art and Theosophy. In reality, there is no such conflict. Harris maintained that once Blavatsky opened up a new aesthetic, art should no longer communicate doctrines through symbols. Modern art ought to purely express an inner experience of beauty for both the creator and the observer. Neither the artist nor the viewer should be directed to step outside the artwork in search of a separate doctrinal meaning.

Harris grappled with this idea throughout his life. He believed it could be discovered in Blavatsky’s remarks about art and form, acknowledging that they could be interpreted in various ways. This partly explains his transition from his early—and quite successful—style to the more debated abstract works of his later years. He felt that while they were beautiful, his early Canadian landscapes could still risk leading the viewers’ thoughts beyond the painting to the actual mountains and lakes “out there.”

Harris insisted that the experience of buddhi should happen within the artwork itself. The painter is the first to encounter buddhi through “ecstasy,” a term that Harris often used. Ecstasy is based on creativity as well as a specific type of asceticism.

The chastity observed in Harris’ relationship with his second wife Bess was not incidental but rather stemmed from their religious beliefs. Both he and Bess asserted in their letters that they adhered strictly to this commitment in the most literal sense, despite skepticism from some friends. This aesthetic asceticism led the artist to forgo any attempts to preach a doctrine or reflect his own personality. Ultimately, Harris ceased to title his works and even stopped signing them. He created some pieces on jute, a material known to quickly degrade. His intention was to affirm that the individual identity of the artist was unimportant and that even the wish to ensure the lasting material existence of artworks would contradict this Theosophical asceticism (which was influenced by Buddhism), where the artist fades away, leaving only beauty and art.

In an unsigned article published in 1933 in “The Canadian Theosophist,” whose author was not—contrary to what some later argued—Harris, but rather Frederick Broughton Housser, we read that “from a spiritual point of view the creative artist, not the business man, typifies America. The creative life, which the real artist represents, is the Theosophical life as it was understood and expounded by the founders of the Theosophical Society. The true artist is an occultist.”

The article is significant for Harris, as he and Housser collaborated on a daily basis during that period. Housser, as an art critic, was considered a representative of Harris’ ideas on art and Theosophy.

Harris’ art was not Theosophical in the sense of illustrating or symbolizing Theosophy (“Atma Buddhi Manas” remains a special case). Instead, Harris contended that it was Theosophical as it represented a divine experience of essential forms. Artists could first encounter this divine reality themselves and then convey it to their audience, without highlighting their own individual identities, but rather drawing the viewer into the artwork, which thus serves as the ultimate site for buddhi.

Harris theorized that there are four different forms of abstract art. The first is “painting which is abstracted from nature.” The second kind “is non-objective, in that it has no relation to anything seen in nature,” but rather tries to convey an idea or message. The third form is a geometrical organization of shapes and proportions, whose perfection Harris saw in the “best painting of the late Dutch artist Mondrian,” a fellow Theosophist. Harris, however, favored the fourth form, “abstract expressionism,” where the artist tries to mobilize his or her “inner resources.”

Harris did not create the formula “abstract expressionism,” but took it from a group of New York abstract artists, which included Jackson Pollock (1912–1956). Pollock had been introduced to Theosophy in high school by his art teacher Frederic John de St. Vrain Schwankowsky (1885–1974), a Theosophist and a member of the Liberal Catholic Church. Schwankowsky led Pollock to attend a retreat with Jiddu Krishnamurti (1895–1986) in Ojai. Although later he lost his enthusiasm for Krishnamurti, Pollock eventually returned to occult and theosophical interests through his friendship with John Graham (1881–1961). Pollock’s art was quite different from Harris’, but the latter used Pollock’s term, “abstract expressionism,” to designate the artistic creation of forms that are not purely subjective but may be appreciated by “every normal person,” since they express a “universal language.”

Harris is still regarded as the most esteemed Canadian artist of the twentieth century. Though the styles of the two art movements he helped establish (the Group of Seven in Canada and the Transcendental Painting Group in New Mexico) faced later critique for being perceived as overly “spiritual” and shaped by the artists’ interest in the esoteric and occult, they played a crucial role in North American contemporary art.

Theosophy was essential for Harris’ artistic journey throughout his entire mature career. His fascination with Theosophy was not a fleeting interest. Like Mondrian, he was an engaged member of the Theosophical Society, but he went further than Mondrian by actively promoting Theosophy through writings, lectures, and a radio program.

Both Mondrian and Harris dismissed symbolism and asserted that authentic Theosophical art should not “preach” Theosophy but should instead utilize Blavatsky’s concepts about forms to create new works that evoke simplicity, beauty, and a connection with the deeper, divine essence of the universe. When considering how abstract art, produced by artists knowledgeable about Theosophy, could fulfill this purpose, Harris spoke of Mondrian’s method with respect but felt that the Dutch artist’s “geometrical” forms were less effective in facilitating the spiritual experiences he sought to evoke compared to “expressionist” abstract art.

The differences in their viewpoints indicate that Blavatsky’s ideas on aesthetics and the arts were not fully fleshed out and could lead talented artists, who were also Theosophists, to arrive at varying conclusions.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.