Perhaps more than any other artist, the Canadian Theosophist studied how Theosophical principles might inspire the visual arts.

by Massimo Introvigne

Article 4 of 5 (published on consecutive Saturdays). Read article 1, article 2, and article 3.

Harris cited various authors from Theosophy. However, in a December 1, 1937, letter addressed to Yvonne McKague Housser, he claimed that only Blavatsky and Judge “were in constant and direct contact with the Great Ones [the Masters], and only their works are truly dependable.” He stressed that one should read Blavatsky and Judge to genuinely understand authentic Theosophy, defined by him as “an all-comprehensive philosophy—a synthesis of Religion, science, and philosophy,” which “the West needed” and “the East had always had.”

In his impactful lectures and radio addresses promoting the Theosophical Society, Harris aimed to portray Theosophy as a straightforward system, centered on three key concepts: monism, karma, and reincarnation. He proposed that our belief in an ideal state reflects evidence of reincarnation. He contended that this conviction cannot stem from our experiences in this present life: “By virtue of what insight do we dare set ourselves up as judges of the imperfections of this world, unless we have known and know a superior realm of being?”

Is this “superior realm” accessible in our current lives? Yes, Harris affirmed, through what he termed a “sixth sense,” aligning with the “aesthetic attitude.” While the early Theosophists may have chosen other terms, the idea of a sixth sense recalling a divine plan remains orthodox within Theosophy.

Harris’ writings linked this to a polemical stance, influenced by Blavatsky, that critiques mainstream religion. He accused “religionists” of prioritizing morality over spirituality, thereby fostering a distorted view of God. According to him, “morals” suggest the existence of an external deity, a lawgiver positioned beyond our universe. In contrast, the aesthetic perspective asserts that a divine essence resides within each individual, gradually revealed through personal, creative endeavors and experiences. According to Harris, the moral viewpoint lacks creativity, is unadventurous, and follows rather than leads. Conversely, the aesthetic perspective is innovative, fertile, and embraces the spirit of adventure at the core of our existence.

This text, written a year before Harris divorced, critiques the rigid moral standards of the Toronto Protestant establishment, which generally viewed divorce unfavorably. Yet, in 1922, Harris had already addressed in his sole poetry collection those who “succumb to secondhand living” and “say nay, nay and smile at aspirations, dreams and visions” due to their reliance on “old dead catch phrases” and antiquated beliefs. This indicates that Harris adopted these views long before his personal challenges arose.

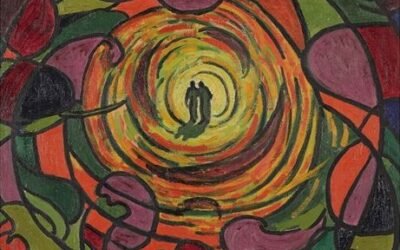

Harris viewed aesthetic experience as fundamentally rooted in beauty. The arts, he believed, “epitomize, intensify and clarify the experience of beauty for us, as nothing else can.” Beauty is seen as a powerful force; it connects us to “the plane of being we Theosophists call buddhi, that is, that eternal plane of being wherein abides the immortal part of man and the universe, and which is beyond sensuality and the intellect and desires, and is the source of all high inspiration and devotion.” This concept of beauty fosters a dual movement: it lifts us towards the divine, to a higher reality, while simultaneously penetrating “all the secret places in the soul; that leaves no dark corner, no twist of hypocrisy, no petty motive, to its own devices, but shows us the stark truth of our pretenses, and our personal perversions, for exactly what they are.”

Art conveys beauty, allowing everyone to appreciate it. It is not only about skill or originality; authenticity is crucial. Harris emphasized that genuine experiences of beauty lead to authentic art. Such art will generate a “double movement,” lifting us to a higher level of existence while purging any falsehood within us, affecting both the artist and the audience.

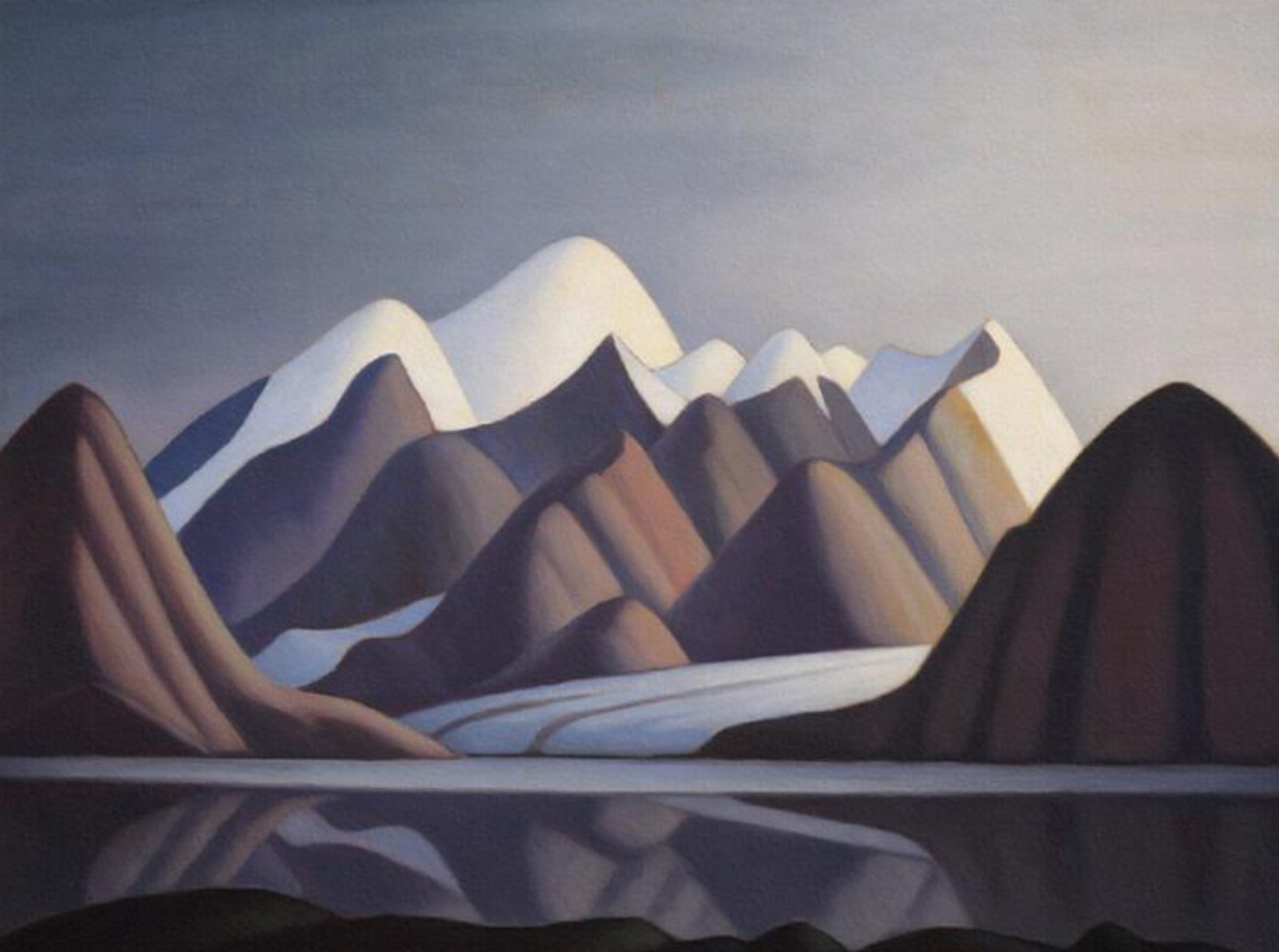

For Harris, art is universal, yet each culture should possess its unique expression. Romanticism brought forth the notion of “the North” as a region particularly conducive to spirituality, influenced by geography and climate. Harris embraced this established Northern Romantic tradition, integrating it with Theosophy, artistic expression, and Canadian nationalism. He critiqued Canadians who depended on European or American models instead of forming a genuinely Canadian art scene. Theosophy added a distinct perspective to his interpretation of Canada’s national tradition, rooted in Blavatsky’s belief that the sixth sub-race of the Aryan root-race was emerging on the American continent. According to Blavatsky, this sixth sub-race would be more spiritual than earlier sub-races, benefiting from North America’s climate, landscape, and burgeoning economic and technological progress.

In the early nineteenth century, Canadian nationalists asserted that Canada possessed a unique identity, separate from Europe and the United States. This identity was deeply rooted in the concept of the “Great North,” which held both geographical and mystical significance. In embracing this tradition, Harris claimed that being close to the Great North offered Canadians economic advantages, a strategic location, and health benefits, while enhancing their spirituality and fostering mysticism. He partially reframed Canadian nationalism through the perspective of American Transcendentalism, which resonated with many Canadian artists. Additionally, he drew inspiration from the ideas of German painter Paul Thiem, whom he encountered during his early years in Berlin. Transcendentalists and Thiem posited that specific landscapes, such as vast wildernesses, forests, and abundant snow, heightened spiritual awareness.

The Transcendentalists and Blavatsky mainly focused on the spiritual characteristics of the Northern landscape in relation to the United States. Harris highlighted the uniqueness of Canadian geography: “The very coolness and clarity of its air, the feel of the soil and rocks, the rhythms of its hills and the rolls of its valleys, from its clear skies, great waters, endless little lakes, streams and forest, from snows and horizons and swift silver. These move into a man’s whole nature and evolve a growing, living response that melts his personal barriers, intensifies his awareness and projects his vision through appearances to the underlying hidden reality.” “Indeed, no man can roam or inhabit the Canadian North”—Harris wrote—“without it affecting him […]. The North will give him a different outlook from men in other lands.”

The artist argued that spending merely two months in Northern Canada would suffice to enhance the freedom and creativity of any true artist. Harris recognized that Blavatsky believed a new race was developing in the United States instead of Canada. Nevertheless, he maintained that the environment in Canada was even more favorable for spiritual growth. “The top of the continent,” he explained, “is a source of spiritual flow that will ever shed clarity into the growing race of America, and we Canadians, being close to this source, seem destined to produce an art somewhat different from our southern fellows, an art more spacious, of a greater living quiet, perhaps of a certain conviction of eternal values. We were not placed between the southern teeming of men and the ample, replenishing North for nothing.” Like Harris, his associate, fellow Theosophist, and co-founder of the Seven, Arthur Lismer, also expressed in “The Canadian Theosophist” his belief that a new sub-race would arise in Canada, as opposed to United States.

The faith of Harris’ mother, Christian Science, supported his argument for Canada. Christian Science emphasized that densely populated areas increase the dangers of negative animal magnetism. Harris wrote, “We in Canada are in different circumstances than the people of the United States. Our population is sparse, the psychic atmosphere comparatively clean, whereas the States fill up and the masses crowd a heavy psychic blanket over nearly all the land.”

Harris recognized the importance of steering clear of any potential racist connotations related to Blavatsky’s concept of root races. In 1933, in response to the heightened focus on the Nazi threat by Canadian media, Harris released an analysis of European political affairs through a Theosophical lens. He reiterated his familiar tirades against organized religion and “the glib priests who turn their backs on any god worthy of the name and serve the god of enmities in man, the god of a tribe or class.” But he also lashed against “the devilish moral cowardice of Germany today, a people who under the cloak of a fanatical belief in the superiority of the Aryan-Germanic racial strain—a myth if there ever was one—make a scape goat of another and utterly helpless people, the Jews.”

Enveloped in its “gigantic abstractions,” Germany failed to grasp Blavatsky’s genuine doctrine of the races. The transition from one race to another, Harris said, should be accomplished through peaceful methods, culture, and the arts rather than violence and warfare.

Massimo Introvigne (born June 14, 1955 in Rome) is an Italian sociologist of religions. He is the founder and managing director of the Center for Studies on New Religions (CESNUR), an international network of scholars who study new religious movements. Introvigne is the author of some 70 books and more than 100 articles in the field of sociology of religion. He was the main author of the Enciclopedia delle religioni in Italia (Encyclopedia of Religions in Italy). He is a member of the editorial board for the Interdisciplinary Journal of Research on Religion and of the executive board of University of California Press’ Nova Religio. From January 5 to December 31, 2011, he has served as the “Representative on combating racism, xenophobia and discrimination, with a special focus on discrimination against Christians and members of other religions” of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE). From 2012 to 2015 he served as chairperson of the Observatory of Religious Liberty, instituted by the Italian Ministry of Foreign Affairs in order to monitor problems of religious liberty on a worldwide scale.